The World Health Organization has confirmed the current outbreak of Ebola virus in Africa is the largest recorded outbreak, killing 672 of the 1201 confirmed cases since February this year.

So it’s no surprise that there’s increasing global concern about the spread of this virus – the situation is undeniably scary. Here’s what you need to know.

What is Ebola virus?

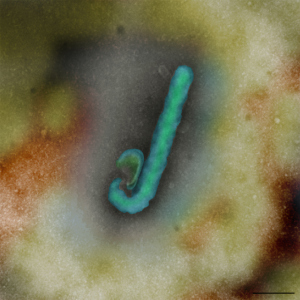

Ebola virus, also known as Ebola hemorrhagic fever, is a highly infectious illness with a fatality rate of up to 90 per cent. The virus is feared for its rapid and aggressive nature. Symptoms initially include a sudden fever as well as joint and muscle aches and then typically progress to vomiting, diarrhoea and, in some cases, internal and external bleeding. Contrary to Hollywood’s depictions, many people do not suffer massive and dramatic blood loss. They instead die from the shutdown of vital organs like the liver and kidneys.

Prior to this current situation, the largest outbreak of Ebola virus involved 425 people in Uganda, in 2000.

Ebola virus is a zoonotic disease – one that passes from animals to people. As with the respiratory diseases SARS and Hendra virus, bats have been identified as the natural host. There is good evidence to suggest other mammals like gorillas, chimpanzees and antelopes are most likely the transmission host to people but the way the infection passes to them from the fruit bats is still not clear.

Why is it called Ebola?

The virus was first discovered in 1976, with two simultaneous outbreaks of the disease – one near the Ebola River in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo), and the other in Nzara, Sudan. Since then more than 1600 deaths have been recorded.

How does the virus spread?

The virus is transmitted from wild animals to people. It can then spread through contact with bodily fluids from someone who is infected, or from exposure to objects like contaminated needles. People most at risk include health workers and family members or others who are in contact with the infected people.

Are there any treatments available?

There is no vaccine or known cure for Ebola virus infection. As with many emerging infectious diseases, treatment is limited to pain management and supportive therapies to counter symptoms like dehydration and lack of oxygen. Public awareness and infection control measures are vital to controlling the spread of disease.

What is CSIRO doing?

We have been researching the Reston ebolavirus strain, which is endemic in parts of Asia, for several years at the Australian Animal Health Laboratory (AAHL) as part of our mandate to study new and emerging infectious diseases to ensure we’re prepared should they ever reach Australia.

In 2013, following approval from the Australian government, we imported several Ebola virus isolates including the Zaire ebolavirus strain from Africa for research purposes. We’re investigating the pathogenicity, or disease causing ability, of these viruses, to understand why the African strains have a high fatality rate in people, compared to the Asian strain, which does not cause human disease.

There are strict international protocols, government approvals and security measures in place to ensure such viruses are transported and imported safely. At AAHL, all work with Ebola viruses is at the highest level of biocontainment, deep within the facility’s solid walls. Our specialist staff must work on the virus wearing fully encapsulated suits with their own external air supply.

Although most of our research is in cell and tissue culture, in the coming weeks our scientists plan to work with ferrets, which have shown human-like responses to infection with other high-risk pathogens, to understand what makes the Ebola virus pathogenic. We believe that understanding the differences in virulence between the two closely related strains of Ebola may hold the key to developing an effective vaccine to prevent this deadly disease, or therapeutics to treat it.

Why is CSIRO involved in the global response to fight this deadly disease?

AAHL has highly specialised capabilities for working with zoonotic diseases. Scientists at AAHL first identified and characterised the deadly Hendra virus, which, like Ebola viruses, is classified as a ‘biosafety level four (BSL4) pathogen’- the most dangerous of viruses, without a known cure or vaccine. The team has since been integral in the development of the Equivac HeV vaccine, now being administered to protect horses and people in Australia.

Located in Geelong, AAHL is one of a handful of high-containment laboratories in the world capable of working on BSL4 pathogens. The facility was built to ensure the containment of the most infectious agents known. It is designed and equipped to enable the safe handling of disease agents such as Ebola virus, at the necessary high containment level.

For more information about the Ebola virus, see the World Health Organization fact sheet.

23rd January 2015 at 6:16 pm

Everyone loves what you guys are usually up too.

This type of clever work and coverage! Keep up the great works guys I’ve added you guys to blogroll.

6th August 2014 at 4:09 pm

Very valid observation @ Chris! You just echoed my own thoughts exactly and in fact what would have happened if the Ebola virus had been found in any animal in the developed world? @ Keith, the stories your friend told you are also true, but is anybody not wondering that given the stated high virulence of the Ebola, the number of deaths recorded at each outbreak has been low compared to say malaria, or HIV? I think the key to the cure is in finding exactly how it moves from the fruit bats to humans. And what starts and halts the flares of outbreaks seemingly without warning.

7th August 2014 at 11:22 am

You are right to mention malaria @ Abi. I think it’s mainly in young children where the death rate is high — several hundred thousand deaths last year I think. However, malaria has an insect vector common in human communities and the death rate of infected people overall is very low compared to Ebola. So 500k deaths seems a lot (2000 airliner crashes!) but is small as a percentage when you realise that 200M or more people are infected. What I’m wondering is whether the people assessing those infected by Ebola are also testing for malaria, other parasites (of which there are plenty) and other viruses. Since Ebola is immunosuppressive (VP24 & VP35 genes), co-infection is probably important for their disease outcome and maybe is involved in answering your question about the occassional appearance of outbreaks — perhaps a combination of factors is required to get the outbreak going, in addition to an infected vector.