By Fiona McFarlane

When one thinks of deadly animals, the likes of sharks, snakes and spiders probably come to mind. But there’s one pesky little critter that takes the cake, and believe it or not, it’s the mosquito.

Small bite, big threat: the Asian tiger mosquito is one pest you don’t want to mess with. Image: Susan Ellis.

Mozzies are responsible for more than one million deaths each year worldwide – that’s more than one hundred times the deaths caused by sharks, crocodiles and box jellyfish combined.

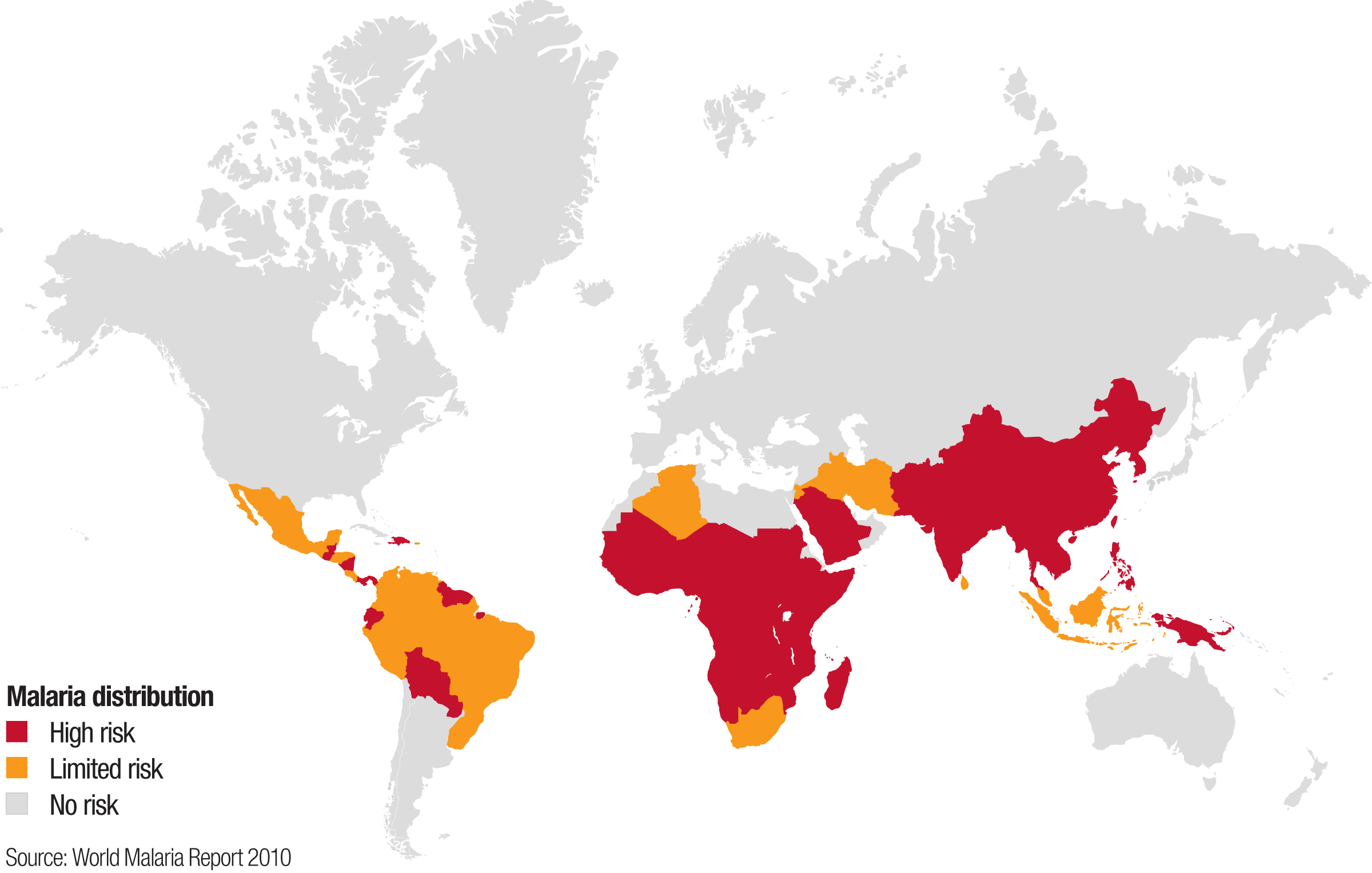

Mosquitoes are best known for carrying malaria, a ‘vector-borne’ disease that around 3.4 billion people – or half of the world’s population – are at risk of contracting.

Vector-borne diseases, such as malaria and dengue fever, are one of the world’s leading causes of death. So it’s no wonder the World Health Organization is focusing on the prevention and control of vector-borne diseases on this year’s World Health Day.

But what are they exactly, and do we need to worry about them here in Australia?’

What are vector-borne diseases?

Vector-borne diseases are caused by disease-producing microorganisms that are transmitted by blood-sucking mosquitoes, ticks and fleas known as vectors. When a vector bites another animal or human, it may transmit pathogens and parasites that can cause serious illness and even death.

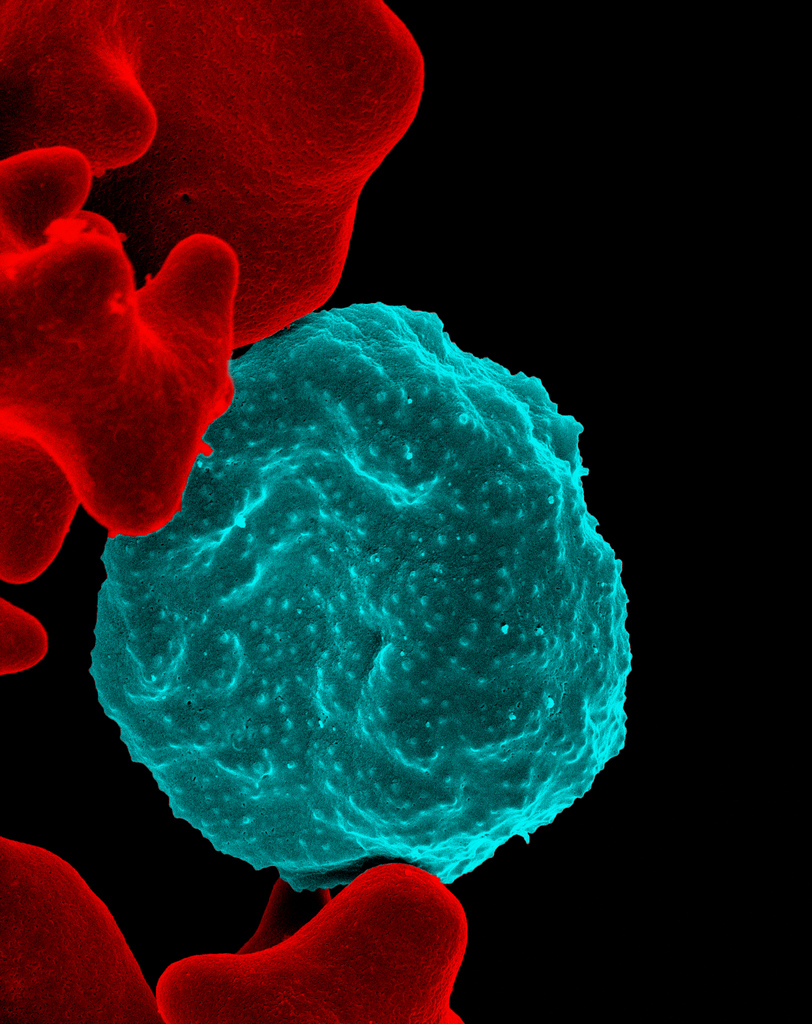

The most deadly vector-borne disease, malaria, caused an estimated 660, 000 deaths in 2010. But the world’s fastest growing vector-borne disease is in fact dengue fever, with a 30-fold increase in incidence during the last 50 years. In fact 40 per cent of the world’s population is at risk of developing this disease.

With the globalisation of travel and trade, unplanned urbanisation and environmental challenges like climate change, the spread of vector-borne diseases is expected to increase around the world. We’re now seeing diseases such as dengue and West Nile encephalitis emerging in countries where they were previously unknown.

Malaria distribution across the globe in 2010. Image: BASF

On the home front

Australia is in the fortunate position of not being home to some of the more serious vector-borne diseases like yellow fever, malaria, West Nile encephalitis, Japanese encephalitis and Rift Valley fever.

If you live in north Queensland chances are you will have heard of outbreaks of dengue fever transmitted by the mosquito Aedes aegypti. But you probably haven’t heard of Chikungunya – another virus transmitted by mosquitoes that causes severe joint pain and fevers for weeks, months and sometimes years.

While the virus is not here in Australia, 126 Australians caught Chikungunya after travelling to Indonesia, India, Malaysia and PNG during 2013 – that’s an increase from 19 cases reported in the previous year.

Other vector-borne diseases such as Ross River fever and Murray Valley encephalitis are already in Australia and are being closely monitored to reduce the spread and impact of on our people.

What are we doing about it?

A red blood cell infected with malaria parasites (blue). Image: NIAID.

Our scientists are well aware of the need to take action and be prepared. They are looking at ways to reduce the transmission of these viruses, develop more effective surveillance and intervention strategies and provide Australians with early warnings of new or exotic diseases.

Recently, we opened a new insectary for the study of vector-borne diseases at our very own Australian Animal Health Laboratory in Geelong Victoria, which houses colonies of mosquitoes. Having access to this facility will allow us to assess the ability of Australian biting insects to transmit dangerous exotic viruses.

We are also investigating the factors that influence how vectors behave in the environment and what viruses they carry. This will help improve our understanding of the virus-vector-host interaction and disease transmission.

Another point of interest is how mosquitoes and other insects develop immunity to the diseases they carry and investigating how we might increase their immunity to stop the transmission of disease.

On the maths front, our mathematical experts are using complex algorithms to predict where mosquitoes might invade and how our resources may be best deployed to fight them. They are also undertaking scoping projects to assess new and innovative approaches to mosquito control.

Other members of the team are working with the Australian National University to reduce the risk of eastern Australia being overrun by the Asian tiger mosquito, also known as the BBQ stopper, which carries diseases like dengue fever and Chikungunya.

While the risk of new and exotic diseases – and the vectors which carry them – reaching Australian shores is very real, our research will continue to help keep Australia safe from harm.