Updated 20 Feb 2020

The latest infectious disease sweeping the globe, the novel coronavirus, has now infected tens of thousands of people. While most of the affected people are in China, the virus has been popping up in cities around the world.

While there have been other types of coronavirus before – think SARS that broke out in 2002-3, or MERS in 2012 – this particular type is new. First spotted in Wuhan, China, scientists think it originated in an animal and spread to humans, then from human to human.

With the rate of travel and global trade today, and the tendency of viruses to rapidly mutate, it can be hard to tell how much of an impact a specific virus might have on the world. Scientists are scrambling to understand this new virus and its behaviour at lightspeed so they can develop, test and produce a new vaccine to protect us.

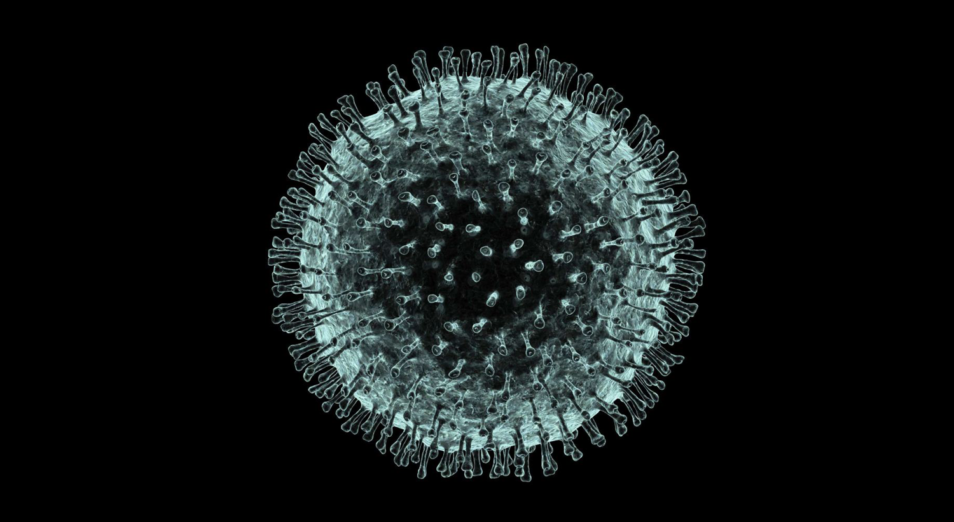

Computer artwork of the new coronavirus, named after its distinctive ‘crown’ of surface proteins. Science Photo Library: PASIEKA

Creating a coronavirus vaccine in months, rather than years

Vaccine development is complicated and lengthy. Traditionally it takes months to years to take a vaccine from development out into the world. It’s a long process of developing possible vaccines, pre-clinical testing, human trials, regulatory approval and large-scale development.

But this isn’t the first time the world has faced down an epidemic. Our own scientists have been heavily involved in infectious disease work. This includes understanding how SARS spreads, tracking the spread of avian flu, developing the Hendra vaccine, and much more. Research organisations have been down this path before, and learned that the best way to speed up the response is to be really, really prepared.

That’s why we’re part of a global alliance: the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI). It aims to derail epidemics by speeding up the development of vaccines. Within the coalition we’re involved in various parts of a rapid vaccine development ‘pipeline’. Each of our organisations form a part of the pipeline, ready to go when an epidemic hits. This way vaccines can be developed, tested and delivered much faster than ever before.

What we’re doing – a team effort

First up, we have sourced a sample of the novel coronavirus – now known as the virus responsible for COVID-19. This sample is from the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, who were the first organisation outside of China to re-create the virus in the lab. This sample has gone to our high-containment facility in Geelong, the Australian Centre for Disease Preparedness (ACDP).

Our highly trained scientists are working in this secure facility to better understand the virus. We’re exploring: how does it behave? How does it infect and spread? And what are its characteristics?

We are working on coronavirus in the secure area of our Australian Animal Health Laboratory in Geelong.

Once we’ve figured that out, our team at AAHL will start pre-clinical testing of new potential vaccines. This includes potential vaccines from the University of Queensland who are already hard at work.

If those tests show a vaccine is successful, other research organisations will be able to move on to full human trials of the vaccine.

We also have advanced manufacturing capabilities that could create the proteins other organisations need in developing new vaccine candidates.

It’s truly a global team effort in response to a global challenge, and the scientific community is moving at unprecedented speed. If all goes well, the world could be looking at a new vaccine in months rather than the usual years. Find out more about how long it will be before a vaccine against the coronavirus is publicly available.

21st February 2020 at 11:12 am

It would be important to know which viral proteins neutralizing antibodies recognize so these proteins, or their corresponding DNA/RNA can be used to produce vaccines.

7th February 2020 at 4:34 pm

Congratulations to our scientists and scientists of the world. we do know that the only way to test the efficacy of the vaccine when it is discovered is to test it on humans after the animal tests are over. which country will be used as a guinea pig i sincerely hope that the infection will not be deliberately spread to poor countries and the saviour comes in the guise of a vaccine designed to test its efficacy in the poorer countries and after the tests have proven to be effective or non effective through deaths of unsuspecting hapless poor people. after all the trials have succeeded then the major pharmacological industries will manufacture the vaccine which will rake

in millions if not billions or trillions of dollars.

i sincerely hope that such a scenario will not eventuate. I wish to warn political leaders of poorer countries to

watch the activities of loving scientists who would want to gift vaccines but in reality they are testing the efficacy of an unknown quantity. Were the birth control pills first tested on unsuspecting Indian woman before this pill was commercially manufactured for sale to the rest of the world.

I urge the UNO and the branch responsible for maintaining the ethics and morality of experimentation.

7th February 2020 at 4:04 pm

The article was about “understanding the corona virus”.

I didn’t learn anything about the virus itself; only how Australian scientists are getting involved.

4th February 2020 at 11:27 pm

The hendra virus looks like a coronavirus, and is similarly sourced from bats. Any chance that the work and/or vaccine for the Hendra virus would be of help in defeating the novel coronavirus?

5th February 2020 at 9:11 am

Hi Shane – thanks for your message.

Hendra virus is not related to the new coronavirus. Hendra is part of the paramyxovirus family, which includes measles and mumps, and is a separate family from coronaviruses. Hendra is carried by flying foxes and occasionally spills over into horses which can then transmit the virus to humans. The animals involved in this new coronavirus outbreak have not yet been identified – a bat origin is highly likely but this doesn’t exclude the possibility of a non-bat species being involved in transmission to humans, such as with the SARS coronavirus which was transmitted from bats to civet cats to humans.

Kind regards,

Kashmi

Team CSIRO

3rd February 2020 at 8:32 pm

Dale, if you are looking for a death rate you need to compare the number who died, with the number ill on the day they got sick. For example, if there were 200 people in hospital on the 20th, and now 200 of them are dead, then this is serious. The fact that 300 are now dead, and 14,000 are now infected is not relevant, as there is no consideration of how many of those 14,000 are going to die over the next 2-3 weeks. Further, this does not consider the number who got sick, but are not hospitalised, but that is probably not a large number n China.