Back in 2014 and 2015 the world was panicking about Ebola when it reached pandemic levels in West Africa. The epidemic killed five times more people than all other known Ebola outbreaks combined. From the first confirmed case in March 2014, more than 11,000 people died from the disease.

Ebola is an often fatal virus that can cause severe bleeding and organ failure. Like most viruses, it started out in animals, in this case most-likely fruit bats, and now it spreads from human to human as well. But is it still a threat? If so, is that threat likely to reach us Down Under? And how would you know if you’d contracted it? Well let’s take a closer look at Ebola.

epaselect epa04343965 A picture made available 07 August shows a Liberian nurse wearing protective clothing during the removal and burial of an Ebola victim in the Virginia community on the outskirts of Monrovia, Liberia, 06 August 2014. Liberia's president has declared a state of emergency in an attempt to stop the Ebola outbreak, which continues to spread across West Africa, a local newspaper reported. According to statistics from the World Health Organisation (WHO), 932 patients have died from Ebola in West Africa with most of the latest deaths reported in Liberia. WHO officials are meeting in Geneva are to discuss the global implications and response to the outbreak. In Nigeria a second person a nurse who treated an Ebola patient has died. EPA/AHMED JALLANZO

The most recent outbreak in West Africa has reminded us that Ebola is still a very real threat. Image: EPA/Ahmed Jallanzo

Can you catch Ebola in Australia?

There have been no cases of Ebola in Australia and if we continue to be vigilant, the chances of it spreading here are unlikely.

It’s important to note that Ebola reached epidemic levels in West Africa mainly because they have suffered from years of civil war and have poor health infrastructure. People frequently travel between built up urban areas and rural areas where they might have contact with wild animals that transfer viruses like Ebola.

Thankfully in Australia we have the facilities to help protect us from disease outbreaks like Ebola. It’s all about containing the virus to cut off the chain of infection. So, for example, hospitals use specially-designed areas for treating patients suspected of having contracted a highly-contagious disease. We also have lots of check points in place for people travelling in and out of the country from areas of the world where there is the potential to contract a deadly disease. But we still need to be vigilant.

What are the symptoms?

The first symptoms of the Ebola virus are the sudden onset of fever, fatigue, muscle pain, headache and sore throat. This is followed by vomiting, diarrhoea, rash, symptoms of impaired kidney and liver function, and in some cases, both internal and external bleeding.

If you get samples to a laboratory, they’ll be looking for low white blood cell and platelet counts and elevated liver enzymes as well as evidence of the virus itself (viral RNA and virus-specific antibodies). The incubation period, that is, the time from infection to the onset of symptoms, is 2 to 21 days. During this incubation period, before the onset of symptoms, the infected person isn’t contagious.

It can be difficult to distinguish Ebola from other infectious diseases such as malaria, typhoid and meningitis. To clinically confirm that symptoms are caused by Ebola a number of diagnostic tests can be used. But you only need to worry if you’ve possibly been in contact with an infected person or animal.

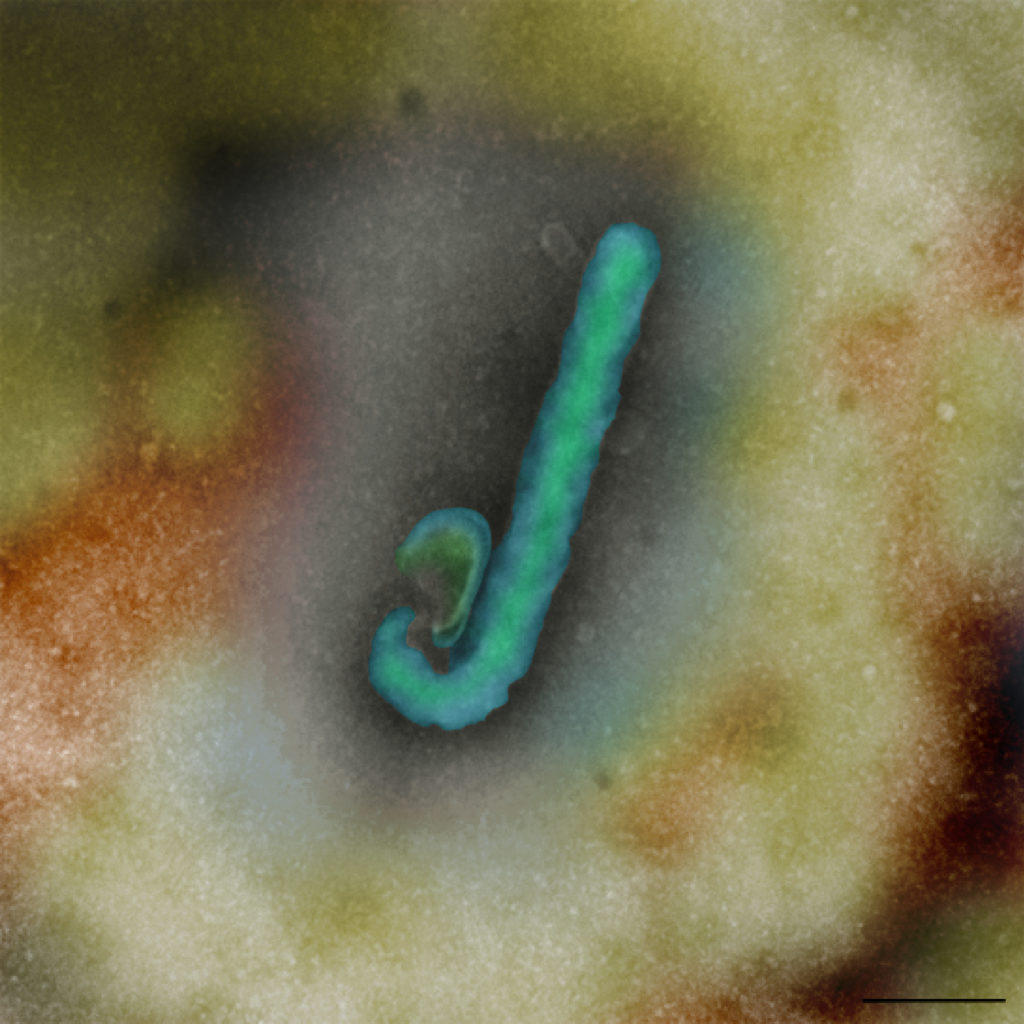

An artificially coloured electron microscope image of Ebola virus

Ebola – one of the most lethal infectious diseases known. An artificially coloured electron microscope image of Ebola virus.

How do you catch it?

Ebola is introduced into the human population through close contact with the blood or other bodily fluids of infected animals such as monkeys, chimpanzees and fruit bats. It can then spread human-to-human in the same way. You can also be infected if you come into direct contact with the bodily fluids of infected people on contaminated surfaces and materials.

Ebola is a contagious virus but unlike a cold or the flu, you can’t catch it from simply sitting next to someone on the bus because it is not known to be airborne.

How can you avoid it?

The best way to avoid catching Ebola is not to travel to a country where there is an Ebola outbreak. If you do travel to an area of the world where the virus is active, then:

- follow good hygiene practices

- avoid direct contact with people or animals that appear to be ill

- don’t eat raw or undercooked meat or any bush meats.

How do you treat it?

There is currently no vaccine for the Ebola virus but there are lots of medical organisations working together to find one, including us.

But Ebola can be treated and people can eventually recover. Although some people who have recovered from Ebola have developed long-term complications, such as joint and vision problems.

Some of the treatment methods include:

- providing intravenous fluids and balancing electrolytes

- maintaining oxygen status and blood pressure

- treating other infections if they occur.

Scientists working on zoonotic agents require the highest level of biosafety

Scientists working on zoonotic agents require the highest level of biosafety

What new research is being done to protect Australia and the world from another Ebola outbreak?

Due to the severity of Ebola infections, work with the virus requires laboratory facilities with the highest level of containment (“Level 4”). For the most part, this means that scientists working with the virus need to wear fully-encapsulated “space suits” with a dedicated air supply, within a laboratory specially-designed to minimise the risk of the virus escaping.

These facilities are expensive, and require continual monitoring and maintenance. As a result, there are only a handful of places in the world where this work can be performed. Within Australia, we conduct Ebola research within the maximum containment laboratories at the Australian Animal Health Laboratory (AAHL) in Geelong. Most of the Ebola research at AAHL is focussed on trying to determine how the virus causes such severe disease in humans, as well as on the development and testing of vaccines and therapeutics to reduce the impact of future outbreaks.

We’re going viral!

We’re heading to Vivid Sydney to give you a peek under the microscope at beautiful and dangerous viruses.

1st June 2018 at 7:20 pm

With what they learned in previous outbreaks why wasn’t this ebola contained immediately, they seem to have dropped the ball yet again.