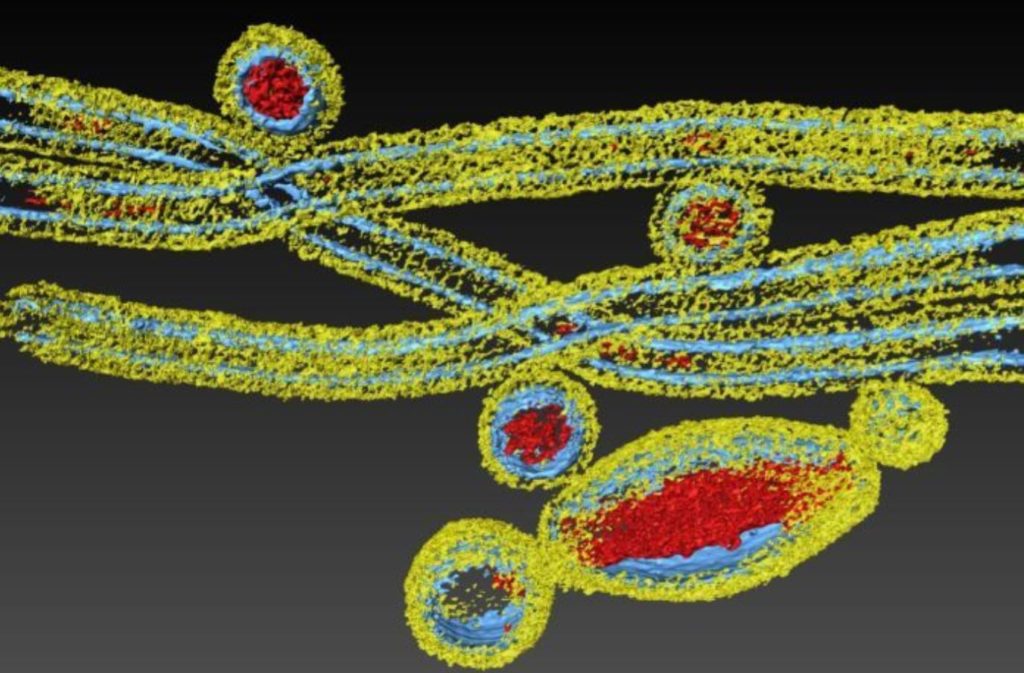

Infectious diseases are as visually beautiful as they are complex. This is from a display as part of the CSIRO's Vivid Sydney display, Beautiful and Dangerous.

Infectious diseases are as visually beautiful as they are complex. This is from a display as part of the CSIRO’s Vivid Sydney display, Beautiful and Dangerous.

This article first appeared on ABC News online.

It starts off as a scratch in the throat, a sneeze, a sniffle. Thinking it’s just a cold, you pop some pills and jump on a plane to the next meeting, unknowingly exposing hundreds more to the time bomb ticking inside.

Internally, your body is mounting a major defence and what happens in the next 24 hours is down to a mixture of your background, health, fitness, vaccination status and a bit of random luck.

By hour 48, you know it’s not a cold, though you might not know you’re carrying a disease responsible for killing hundreds of millions of people. Influenza.

After two flights, four restaurants, an overnight stay in a busy hotel and two days of workshops, over the past 48 hours, like a snail’s trail on a concrete path, you’ve left your own trail, exposing hundreds of people.

Infections diseases: beautiful and complex

With just weeks before the flu season officially starts, infectious diseases like influenza, Ebola and Zika are set to burn the Australian night sky as part of this year’s Sydney Vivid festival.

Infectious diseases are as visually beautiful as they are complex. Their ability to make constant genetic tweaks has in many instances kept them one step ahead of science. As we develop one treatment, the virus can shift, and another has to be made.

The topic of infectious disease is also under the spotlight of the global stage.

Most recently, Bill Gates said an infectious disease pandemic posed the greatest immediate threat to humanity. But globally, he warned, we are not prepared.

According to Mr Gates, to get the world’s defences in order it would cost $US3.4 billion a year — an enormous challenge in a debt-ridden global economy.

In 1918 when Spanish influenza hit the world, about one in 10 people died. The global population was close to 2 billion at the time.

While we haven’t seen a pandemic near that level since then, scientists acknowledge it’s only a matter of time before nature throws us something as deadly.

Influenza A virus H3N2, part of the Vivid Sydney installation Beautiful and Dangerous.

Influenza A virus H3N2, part of the Vivid Sydney installation Beautiful and Dangerous.

Pandemic prevention better than a cure

And although our scientific knowledge has grown since 1918, so too has the global population. It currently sits at about 7.6 billion, three-and-a-half times more than it was when the world was hit 100 years ago.

It can be easy to immediately think about reactive approaches like developing new treatments and vaccines, but if we can predict pandemics it means we can actually prevent them from happening in the first place.

Although it’s no secret, many people don’t realise the most threatening infectious diseases originate in animals, and at some point mutate and infect humans. Zika came from mosquitos, SARS came from bats, swine flu from pigs and influenza A from birds.

While not necessarily visible, for years CSIRO researchers have been tracking diseases across a range of animals, testing and monitoring to catch the sweet spot when genetic changes driven by the virus make it possible for a disease to make the jump to people.

Part of this research includes developing treatments and vaccines for the animals themselves.

Our highly-contained laboratory in Geelong — the Australian Animal Health Laboratory — is one of just a handful of places in the world where scientists can research untreatable diseases like Ebola.

Approaches must be global, not country-specific

And while there is other groundbreaking research going on across other countries and research agencies, approaches have remained very much country-specific, a nod to past times when we lived in a less globally connected world.

Influenza high risk groups

– Children between 6 months and five years of age

– People over five who have certain medical conditions which increase the risk of complications from the flu

– Pregnant women

– Aboriginal people over the age of 15

– Adults over the age of 65.

– But this is a global problem that needs a global approach.

We’ve come a long way since 1918, but there is still much more work to be done if we’re to be fully prepared for the world’s next deadly pandemic.

CSIRO, Australia’s national science agency, is collaborating with Vivid Sydney in 2018. Beautiful and Dangerous takes visitors on a personal encounter with the deadly diseases that most affect human health — magnified to spectacular scale.

In partnership with the Garvan Institute of Medical Research, it provides a glimpse into how we are using science to tackle the world’s greatest challenges.

Dr Rob Grenfell is the CSIRO’s director of health and biosecurity.

Beautiful and dangerous

Get an intimate encounter with beautiful but dangerous viruses and bacteria that infect humanity.

19th February 2019 at 9:01 pm

At 71 and after one bout of the real deal influenza, I’m happy to have a vacc’ but health dept hotline is lacking in info on my egg white allergy/intolerance only had for last 10yrs. My symptoms don’t fit their fairly limited guidelines, any ideas would be gratefully received. Cheers Patricia