Africa is the world’s second largest and second most-populous continent. It’s home to 55 countries but often when we hear about issues like poverty, famine or sanitation people tend to group all of them together under the banner of Africa. But there are some big differences between Nigeria and Somalia, for example. And again, within these countries there are big cities and smaller regional communities which don’t have the same experiences, especially when it comes to some of the basic necessities of life like food, education and health. That’s why it’s so important that we look much closer.

Sustainable Development Goals

In 2015, 193 countries adopted the United Nations 17 Sustainable Development Goals with an aim to working towards them by the end of 2030. These goals are very ambitious. They include things like no poverty, zero hunger, gender equality, affordable clean energy and quality education. The goals are the responsibility of all the nations that have adopted them, not just developing countries so we all have a role to play in sustainable development for our world.

How are African nations tracking?

A new scientific study out of the University of Washington has found that while nearly all nations in Africa have at least one region where children’s health is improving, not a single country is expected to end childhood malnutrition by 2030. The researchers mapped the entire African continent in 5×5 square kilometres on health and education. A level of granularity that has never been achieved before. And that’s important because on the surface when you look at the whole continent it might look like there are areas of improvement, there are also areas that are seeing deterioration in health and education.

One of the main areas that the researchers looked at was children’s growth. Inadequate or improper nutrition, especially before age five, is closely associated with poor health and brain development, as well as increased risks for disease and even early death. The study examined something called ‘child growth failure’ which is defined as insufficient height and weight for a given age and exhibited by stunting, wasting, and underweight among children under 5. Stunting refers to insufficient height for a child’s age; underweight means insufficient weight for a child’s age; and wasting refers to insufficient weight for a child’s height and can result from a combination of stunting and underweight.

The other great detail in this research is the merging of research and data from agriculture, geography, education, to public health. This helps us see a much clearer picture of where different data intersects. For example, we know that education and nutrition are critical factors improving health outcomes and future opportunities Increases in basic schooling, particularly in young women, are linked to improved health for mothers and children.

A mosaic of small croplands, pasture, and forest in Uganda. Most of sub-Saharan Africa is dominated by smallholder farming, though in many cases systems are less dense as farms use less productive or more arid land for grazing livestock and other practices.

Getting the right nutrients

That’s where we come in. We contributed key data maps of agricultural production and nutrient diversity which, together with the rest of the maps and data, were used to explain child growth failure. For the first time, our spatial data on agricultural production and nutrient diversity was linked to child growth stunting. This helped the University of Washington researchers to achieve a more complete and robust analysis. While our data helps to explain some of the reasons for child growth stunting it is only part of the picture as there are many causes of child growth stunting such as socio-economic or environmental variables. It is, however, very exciting that data from multiple disciplines are being used to create a more holistic picture of the reasons for child growth failure.

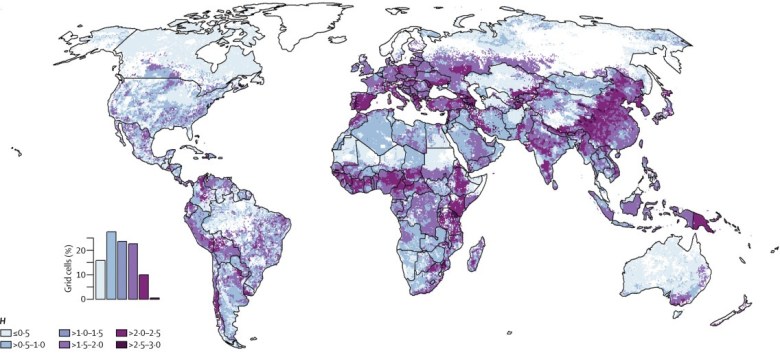

Map of global diversity of food commodities. Diversity is represented by the Shannon diversity index, H, which represents how many different types of foods are produced in a pixel and how evenly these different types are distributed. The higher the Shannon index, the higher the diversity.

What did they find?

The researchers found that all African nations were unlikely to achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal which covers malnutrition, hunger, and food sufficiency by 2030 and that more progress is needed. But they did see some areas of improvement for some nations. There was notable improvement in the prevalence of stunting in Algeria, Mozambique, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, and southern Nigeria. The prevalence of underweight dropped significantly in Rwanda, and, to a lesser extent, in select areas of Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Angola. And the prevalence of wasting decreased considerably in DRC over the past 15 years.

However, researchers found persistently high prevalence of stunting, wasting, and underweight in 14 countries stretching the length of the African Sahel from Senegal in the west to Eritrea in the east. For example, in 2015, South Sudan, Chad, Ethiopia, Somalia, and northern Nigeria all continued to have large regions with high levels of stunting, wasting, and underweight.

And while this is not good news, the research showing this level of detail means that interventions and support can be targeted to the areas that need it most. This data at very precise local levels gives all of us who care about improving people’s lives – from clinicians and teachers to donors and policy-makers – vital insights into where to focus resources to prevent vulnerable communities from falling further behind.

Pingback: Spatial data everywhere, but is that enough? - Agriculture

Pingback: Spatial data everywhere – Agricultural Biodiversity Weblog