Cape York Peninsula is a highly biodiverse area the size of the United Kingdom. Image credit: Niels Photography

All over the world, biodiversity abounds. In Australia our rainforests are bursting with species found nowhere else on Earth. When the sun sets on our deserts, all kinds of unique animals emerge. And, our woodland birds greet each day with a chorus of song.

When you experience such biodiversity, you naturally want to share it with others. Unfortunately, up to half a million species are facing extinction in the coming decades. We need to look after their natural habitat which is under imminent threat. So, which places, animals or plants do we protect?

Where do we start with biodiversity conservation?

Most people would immediately think of lush sweeping landscapes, places not subject to negative impacts from humans. In Australia you might think of Cape York Peninsula in Queensland. Where tree-kangaroos jump between trees. And palm cockatoos use sticks to drum rhythms on wood. Or you might be dreaming of the cool wet rainforests of Tasmania. There, moss-covered King Billy pines up to 2000 years old dwarf giant grass trees.

A stand of giant grass trees or pandanus Richea pandanifolia in south west Tasmania. Image credit: Karel Mokany

On the other hand, maybe when you think of biodiversity, you picture the vast deserts of central Australia. Clear blue skies with sun-drenched red earth and green and gold foliage, pure magic!

Kata Tjuta – the Olgas – in the Northern Territory is a natural wonder and a cultural landmark. Image credit: Karel Mokany

Places like Kata Tjuta are home to thorny devils who gobble ants, and spinifex hopping mice that dash about by night. And below the sand the southern marsupial mole quietly digs its life away.

Thorny devils Moloch horridus live in dry sand country, spinifex grasslands and scrub. Image credit: Christopher Watson

Good things, small packages

We have so many expansive National Parks and natural places in Australia. But what about those small parks and reserves on the doorsteps of our big cities? Should we look after these little fragments of nature threatened by development? Though small, they are sometimes the only habitat for certain species.

For example, the little Truganina cemetery just outside Melbourne. It’s a sanctuary for rare plant species. This includes the endangered button wrinklewort and the magenta storksbill.

The button wrinklewort is an endangered daisy found around Melbourne. Image credit: Jo Lynch

The fragments of grassland around Melbourne’s outer suburbs are home to many endangered species. These grasslands provide habitat for the critically endangered golden sun moth.

Female golden sun moth lives in grasslands around the city of Melbourne. Image credit: Leo via Flickr

You probably wouldn’t expect a rubbish tip to be home for rare animals, but it is. In fact, the only population of the Eastern Barred Bandicoot on mainland Australia live in western Victoria, amongst old car-bodies. There’s actually a children’s book all about them! When discovered, they were fast approaching extinction.

Humans have degraded many forests in south east Asia, but they’re still incredibly important for biodiversity. Some are the last safe havens for rare animals and plants.

So, how do we decide which areas to protect for our precious biodiversity?

The Eastern Barred Bandicoot discovered at a tip in western Victoria. Image credit: JJ Harrison

Mapping the world’s most biodiverse places

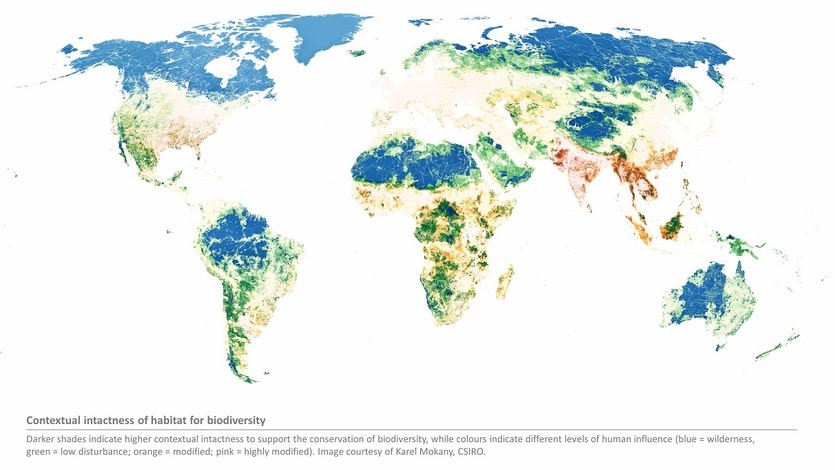

Our scientists have released a study mapping the most high-value biodiversity habitats around the globe.

Our research scientist Karel Mokany and his team worked with the Wildlife Conservation Society on the project. “Our study shows which areas of natural habitat around the world are most important to retain and protect to promote biodiversity. Large areas of wilderness and small habitats with high levels of human impact are both important to protect biodiversity,” Karel explained.

The map is created using large data sets for over 400,000 species and modelling based on our global biodiversity assessment system, BILBI.

Living in harmony with nature

Importantly, the study reveals most of the high-value habitats around the world are not protected. The map is at such fine resolution it allows decision-makers to focus their conservation efforts. If we focus on high-value biodiversity areas we can better meet international biodiversity goals. “This information can play a key role in international biodiversity discussions, which should be based on the best available science,” Karel said.

Consequently, this year is particularly important for biodiversity. The world’s nations will develop and adopt a new post-2020 global biodiversity framework. This comes under the Convention on Biological Diversity. Governments will commit to targets and actions to halt the loss of biodiversity. The goal for 2050 is “Living in harmony with nature”.

In addition – the study can be used to see how we’re tracking against our new goals. And the stakes are high. Imagine a world without koalas, numbats, quokkas or orange-bellied parrots. Um, no thanks!

Protecting the habitat we have left is crucial in limiting future extinctions.

The Magenta Storksbill found at the Truganina Cemetery.

What can you do to make a difference?

Our state and federal governments have a huge impact on protecting habitat for biodiversity. But as Karel explains, everyone has a role. “There are a lot of decisions we all make that can also help maintain our unique plants and animals,” he said.

For example, Karel suggests:

- buying accredited sustainable products

- making ethical financial investments

- minimising your carbon footprint

- joining a local Landcare group.

And finally, you can do your part and help better understand biodiversity change by participating in citizen science initiatives. and you can check out our global biodiversity assessment system BILBI.

1st May 2020 at 4:35 pm

A lot of problems with this post. First, the claim that half a million species are at risk of extinction is simply not credible. The original research report said this might happen over the next 80 years and, if the last 2o years are anything to go by, we will see an end to human population growth on the planet by 2050 and we will see ongoing successes at conserving endangered species. This is scaremongering by suggesting that the absolute worst-case scenario is the most likely.

Second, the map shows many wilderness areas around the world when the scientific definition of wilderness means that there is no noticable or measurable influence from human beings. Almost all the so-called wilderness areas have had people living in them and modifying them for thousands of years.

Third, the link between wilderness and species conservation is not strong.

Fourth, south west Western Australia is a world biodiversity hotspot, yet the map shows it as highly modified, implying it’s of low biodiversity importance.

Fifth, this is the first time I’ve seen biodiversity conservation assessed primarily on the intactness of habitat. I think you need to do a better job of establishing and explaining the link.