Over the last few years, hundreds of Victorians have found themselves with a mysterious affliction: a wound which just won’t heal.

It starts out as a harmless-looking spot. At first, it could be mistaken for an insect or a spider bite. Then it gradually morphs into a scab, a lump, and—most of the time—becomes a painful, swollen ulcer that gets bigger and bigger, and refuses to heal.

Treatment is possible, but it can be difficult. If left untreated, the ulcer can cause permanent scarring and damage.

Cases of the ulcer have increased significantly over the past few years. But no-one has definitively figured out know how it spreads, and how we can prevent it.

This is the mystery of Buruli ulcer.

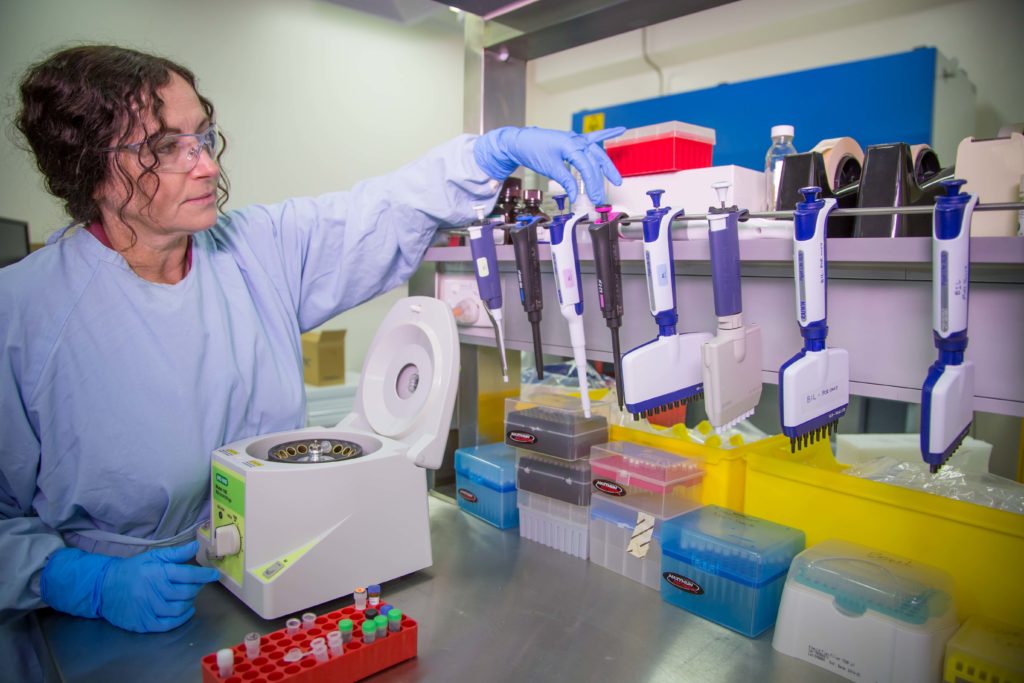

Experimental Scientist Vicky Boyd is leading our lab work on Buruli ulcer.

Buruli ulcer, Bairnsdale ulcer, Daintree ulcer, flesh-eating bacteria … what is it?

Sometimes called the flesh-eating bacteria, Buruli ulcer is an infection of the skin and soft tissue. It’s caused by the Mycobacterium ulcerans bacterium, which is related to the bacteria species that cause leprosy and tuberculosis.

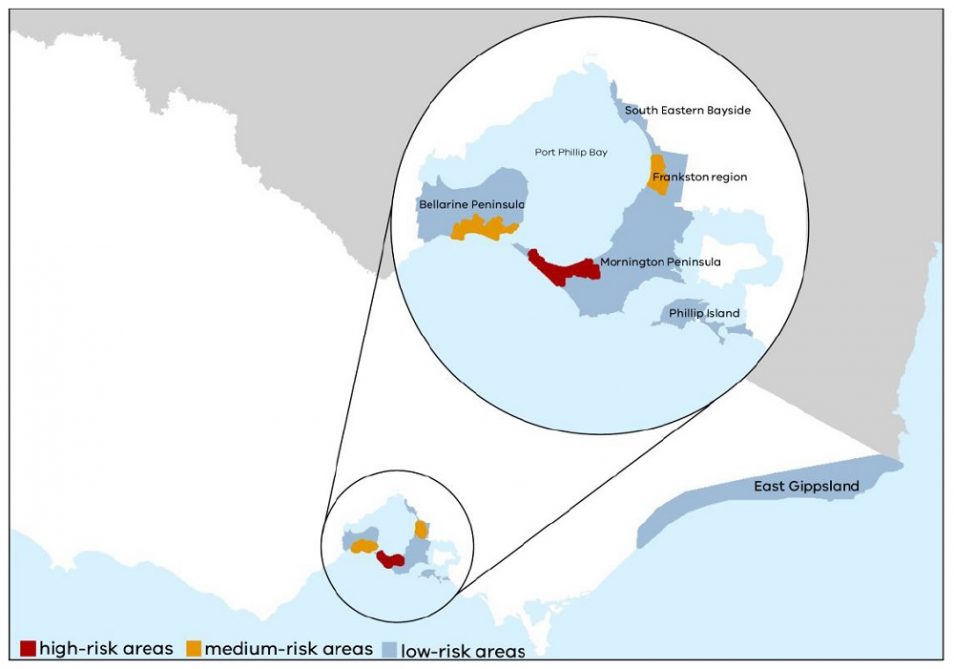

There are about 2000 cases of the ulcer reported worldwide every year—most cases come from tropical regions in Africa. Cases have been reported in Queensland, New South Wales, Western Australia and the Northern Territory over the years. But most Aussie cases have been in the temperate region of south-eastern Victoria, on the Mornington Peninsula, Bellarine Peninsula, South Eastern Bayside, Frankston, and surrounds.

Adding to the puzzle is the fact that Buruli cases in Australia have multiplied in recent years—there has been a 50% increase, year on year, since 2015. In 2017, 275 cases were reported, and last year the number of cases hit 340.

A doctor usually diagnoses Buruli based on where a person lives, their travel history, a physical examination, and swabs or a biopsy (examining a tissue sample). Treatment involves a course of special oral antibiotics, regular dressings, and occasionally surgery. Healing usually takes three to six months depending on how big the ulcer is—so early diagnosis and treatment is pretty important.

What do we know so far?

Scientists have worked on this puzzle for years. So far, we understand that people pick up the infection from the environment somehow, rather than picking it up from another person. But we don’t know exactly how the bacteria infects humans, or where the bacteria like to live in the environment.

It takes between two to nine months between exposure to the bacteria and the onset of symptoms (the average time is 4.5 months). It can also take a long time to get an accurate diagnosis. This delay makes it even harder to identify how a person may have picked up the bacteria in the first place.

Early research has shown that mozzies or other animals may be involved in spreading Buruli. But there may be other ways that the ulcer spreads—and this is the heart of the problem we’re trying to solve.

Areas in Victoria affected by Buruli ulcer. Credit: Department of Health and Human Services Victoria, Beating Buruli in Victoria

Solving the mystery to beat Buruli

We’re trying to better understand how Buruli ulcer is transmitted. And we want to find effective ways to prevent and reduce infections. We’re doing this through a joint partnership with Victoria’s Department of Health and Human Services. As well as the Doherty Institute, Barwon Health, Austin Health, Agribio, the University of Melbourne and Mornington Peninsula Shire.

Our infectious disease researchers are working with communities affected by the ulcer, to survey people who have, and haven’t, been infected.

Our researchers are also taking environmental samples including soil, water, insects and animal droppings from affected and non-affected areas, and analysing the samples at our Australian Centre for Disease Preparedness (formerly the Australian Animal Health Laboratory). This work is expected to wrap up by about early 2020.

We’re relying on the community to help us solve the Buruli puzzle. If you live in Victoria and were diagnosed with the disease after 10 June 2018, and you’d like to get involved in our study, please contact us via kim.blasdell@csiro.au. If you receive our questionnaire and haven’t had the infection, please fill it in as your answers are extremely valuable.

How to protect yourself from Buruli, in the meantime

While the rise of Buruli is a real concern, the overall risk of getting the infection is still low. Even in the areas where the infection is always around.

But if you are in the affected regions, it makes sense to protect yourself from potential sources. These include soil where the bacteria is naturally found. Also insect bites, and puncture injuries from thorns and plants. Try:

- Wearing gardening gloves and covering up arms and legs when gardening

- Using repellents and long clothing to stave off insect bites

- Treating and covering any cuts or abrasions

- Visiting your doctor if you have a skin lesion that won’t heal or is progressing quickly

- Mentioning the possibility of Buruli ulcer.

17th July 2022 at 11:28 am

It’s a little creature that needs to breathe thus if you cover its infected pus hole that it creates which you, can think of as its snorkel hole, it will suffocate and die. I personally prefer a petroleum jelly based cream to cover it with as it’s nice and thick and stays on the skin. I usually keep the infected hole covered for atleast a week. Don’t use bandaids to cover it with as bandaids are breathable. Good luck 🙂

23rd October 2020 at 8:34 pm

Replying to Catherine Roadknight, i have the same ulcer it started off approximately as large as a 5 cent piece. Went to the doctor and was put on Antibiotics didn’t do much for the ulcer and never have been one for Antibiotics.The Ulcer had grown much larger in size after about 4 to 6 weeks. So have read your remedy for the Ulcer so have started this treatment. Would like to know how large your ulcer was prior to starting the treatment Regards Tony Gigliotti