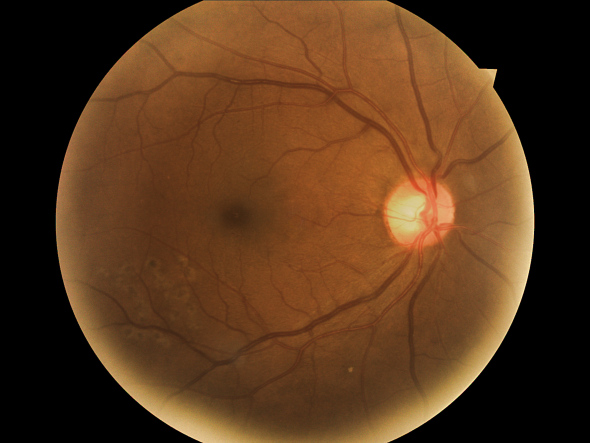

Medical service via the net: an image of a patient’s retina, pictured here, can be easily sent to an ophthalmologist to review.

We can thank high speed internet for many things: the social media revolution, streaming services like Netflix and iView, and a never ending supply of cat videos on YouTube.

But it also has applications in the real world, providing connections to people and places that may otherwise miss out on services and technology that are otherwise taken for granted.

The perfect example of this? Remote-I: our new healthcare technology that uses satellite broadband to help prevent blindness in remote communities.

It’s a high-tech but simple solution to a widespread problem for Indigenous Australians, known as diabetic retinopathy, or DR.

DR, which can affect any diabetes sufferer, damages the small blood vessels in the light-sensitive tissue in the retina (nerve layer at the back of the eye) which leads to vision loss. According to a 2008 National Indigenous Eye Health Survey, around 1 in 16 Indigenous people have diabetes, and of these people with diabetes around one in three have DR. Diabetes was the cause of 13% of vision loss and 9% of blindness among Indigenous adults.

Not only does DR affect the Indigenous population at nearly four times the rate of the non-Indigenous population, it’s also estimated only one in five Indigenous people with diabetes has had an eye exam in the last year. DR can be avoided by having regular eye checks, however those in remote communities simply don’t have access to these services.

Patients’ retinal images and health data can be sent from a remote community health clinic to the desk of a city based ophthalmologist.

Enter Remote-I. Developed by Prof Yogi Kanagasingam and his team, the Remote-I platform works by capturing high-resolution images of a patient’s retina with a low-cost retinal camera, which are then uploaded over satellite broadband by a local health worker.

Then comes the really cool part: once the health worker uploads the patient’s image, an ophthalmologist can access it anywhere at any time. It takes about five minutes to read the images, create the report, and then send it back to the health worker.

The team recently trialed the technology in the Torres Strait Islands and southern Western Australia. As part of the trial, over 1,000 patients received a free eye screening appointment at a local community health centre.

The screening program identified 68 patients who were at high risk of going blind.

The technology also has the potential to benefit older Australians living in remote areas who may have trouble accessing medical facilities

According to Yogi, technologies like Remote-I can help close the gap in access to healthcare in remote and regional Australia.

“If we can pick up early changes and provide the appropriate intervention, we can actually prevent blindness,” says Yogi.

“After our successful trials, we’re really looking to see how we can work with governments and health care providers to continue the roll-out of this technology across other states and territories.

Yogi and his team are also conducting trials to further refine the Remote-I system with a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) development grant to create an algorithm that can automatically identify all the pathologies related to diabetic retinopathy, and send them for referral.

After achieving such successful results in Australia, we’ve also licensed Remote-I to a Silicon Valley spin-off TeleMedC, which plan to take the technology to the US and world market as part of its ‘EyeScan’ diagnostic solution.