Gluten levels vary in different beers.

Like many Australians, Justin Pedersen likes a good beer. But since cutting down on gluten four years ago, his beer drinking habits have changed. Before tasting any of his favourite beers, he uses a testing kit — akin to a pregnancy test — in search of a low-gluten option.

“There seems to be a huge variation in how much gluten is in some products,” Mr Pedersen said.

“They might look and taste the same, and yet one will contain a really high amount and I can’t drink it, and the one right next to it … will test as gluten-free on a test strip.”

Mr Pedersen is one of a growing number of Australians who avoid gluten or wheat. But is it really possible to avoid gluten if you drink beer? Do different types of beers have different levels of gluten? And how accurate are the tests?

Let’s start with the grains

Barley and wheat — the main grains used in beer — contain a group of related proteins that cause inflammation, explains Michelle Colgrave of the CSIRO. Dr Colgrave’s team at the CSIRO studies gluten levels in grains and developed a low-gluten variety of barley used in some beers.

“There could be up to 100 gluten proteins in wheat, probably 50 in barley,” Dr Colgrave said.

In wheat, these proteins are known as gliadins and glutenins, while barley has a family of hordeins. Similar proteins are found in rye, spelt and oats.

“The proteins have different structures, they have different sizes, but they share some common features make them resistant to digestion and also trigger the coeliac response,” Dr Colgrave said.

Coeliac disease is an autoimmune reaction to gluten that destroys the lining of the small intestine and causes inflammation in other organs. Around 1 per cent of Australians are diagnosed with coeliac disease and at least another 1 per cent have the disease, but are undiagnosed.

While these people need to stick to a strict gluten-free diet for life, up to 30 per cent of Australians are cutting down on gluten because of the belief it is healthier, Dr Colgrave said. Just how much gluten a traditional beer contains depends upon the brewing process.

In Germany, beer can only be made out of barley.

The basics of how beer is made

Standard beer is made out of four ingredients: barley or wheat, hops, water and yeast. The barley or wheat is soaked in water to start germination — a process called malting — then heated.

“The reason you malt the grain is to break down some of the starch and turn it into sugars,” Dr Colgrave explained.

Malting helps develop flavour and style.

“If you want to make a pale beer like a lager, then the grain isn’t heated as much during the malting process.

“Whereas if you’re talking about a chocolate-like beer, more along the lines of your Guinnesses, they’re made from what we call a dark chocolate malt.”

The malted grain is then put into hot water where natural enzymes break down the starches. This process, known as mashing, produces a sugary syrup called wort. Hops, once used to preserve the brew, is added to drive flavour such as bitterness. The sugary wort is then boiled, cooled and strained in a process called lautering. Then it is placed in vats with yeast to ferment.

“Those sugars are the source that yeast uses to convert to alcohol and the CO2 or gas that gives beer its fizz,” Dr Colgrave said.

The final product is filtered and packaged ready for your enjoyment.

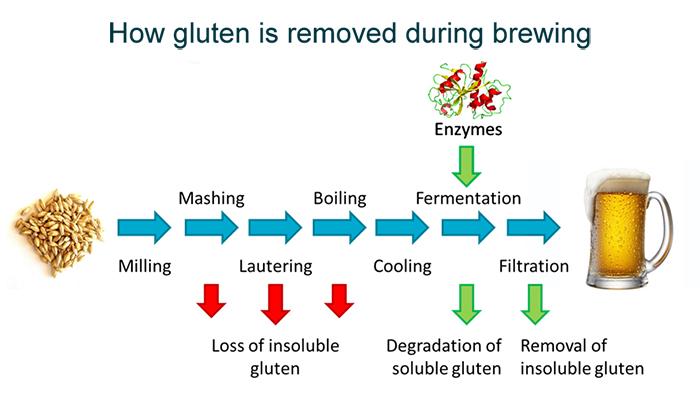

Red arrows show where gluten is reduced during the natural brewing process, and green arrows show where gluten is removed during the production of reduced or low gluten brews. Supplied: Michelle Colgrave

Brewing breaks down gluten … a bit

Along the way, gluten is reduced in beers through a number of steps. First, natural enzymes break down gluten into fragments during malting, mashing and lautering. Then, during heating and cooling, some of the protein rises to the top and can be removed by filtration, explained Dr Colgrave.

“So during a standard brewing process you will have … up to 70 per cent reduction in gluten,” she said.

But there is no rule of thumb for which standard beers have lower gluten content.

“It will depend upon the style of brewing, the type of grain you started with, and many, many factors.”

Some brewers also use sugar syrups or another grain to replace some of the barley, add more enzymes during fermentation to break down gluten faster, or filter using silica to remove more gluten to make low or reduced gluten brews.

Is my beer no gluten or low gluten?

This is where things start getting tricky. Australia and New Zealand have the tightest standards for the definition of gluten-free anywhere in the world, said gastroenterologist Jason Tye-Din of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute.

In Australia, foods labelled “gluten-free” must contain no discernible levels of gluten, or be made of barley, wheat, rye or oats.

The only gluten-free beers available in Australia are made of pseudo grains such as buckwheat or gluten-free grains such as millet, sorghum, corn or rice. But if you’re travelling overseas to the US, UK and Europe, products labelled gluten-free can contain up to 20 parts per million.

Dr Tye-Din said there had been discussions about bumping the Australian labelling standards up to the level used overseas but “there has been inadequate data to guide what really has been a safe threshold of gluten for people with coeliac disease”.

Testing by beer brewers may not pick up all the gluten in beer.

Under the same standards, products labelled “low” or “reduced” gluten in Australia must contain less than 200 ppm — or 20 milligrams per 100 grams. But the safety of this level for people with coeliac disease is also up for debate.

The problem is, even though the tests used by manufacturers such as ELISA are very sensitive, they may not detect all the gluten in beer.

“They’re good at measuring intact gluten, and they are specifically good at measuring intact wheat gluten,” Dr Colgrave explained.

But they are not good at detecting protein that has been degraded into fragments by the brewing process.

“Our research, and research that has occurred in the US, has shown that for the most part a lot of those protein pieces remain, but the tests can’t see them,” Dr Colgrave said.

It is unclear whether or not those protein fragments are still toxic. In 2012, her team used a technique called mass spectrometry, which can identify protein fragments, to analyse 60 beers from around the world.

“We showed all the beers that are made from sorghums and millets and those types of grains were completely devoid of gluten.

“[But] when we looked at beers labelled low-gluten or reduced gluten, there wasn’t much difference in the level we saw in those and what we saw in just normal, off-the-shelf beer.”

A follow-up study last year comparing commercial and low-gluten brands made using additives, additional enzymes and filtering processes came to a similar conclusion.

“We don’t think manufacturers are doing anything wrong. They are using the best tools they have available, they’re following all the protocols, they’re measuring their products, but if the tool cannot give them an answer, there’s very little they can do,” Dr Colgrave said.

So does this mean you should use a home-testing kit like the one used by Mr Pedersen before downing your favourite coldie?

What should a gluten-challenged beer lover do?

Dr Colgrave hasn’t assessed home-based kits, but she suspects they will have the same limitations as the commercial tests.

“They do have the same type of technology, which is the antibodies that would be used in ELISA,” she explained.

“I suspect it would also be unable to detect the small pieces.

“I would not recommend relying on any of the current tests that are available for measuring hydrolysed gluten — so that’s beer, soya sauce or anything where you’ve got these fermentation processes.”

Dr Tye-Din agreed, adding that the kits may be impractical to use and may not get reliable readings for many foods.

“A big issue is the need to adequately sample and then blend the food, and the effect of different food matrices on the sensitivity of gluten detection means the reliability will depend on the food product components being tested,” Dr Tye-Din said.

Gluten affects different people in different ways. People with health conditions such as coeliac disease or gluten sensitivity should only make changes to their diet under medical supervision, Dr Colgrave advised.

“Use your medical practitioner so they can monitor any effects over time,” she said.

“The effects may not be acute, you may not come down with the symptoms straight away, but there can be chronic issues.

“If you want to be 100 per cent safe and conservative, the best bet is to avoid the gluten-containing grains altogether.”

German brewer Radeberger’s Pionier gluten free beer, brewed using our ultra-low gluten Kebari® barley

Coeliac disease vs gluten sensitivity

- Coeliac disease affects around one in 70 Australians

- It is an autoimmune condition that destroys the villi (pictured above) that line the small intestine. This affects the ability to absorb nutrients.

- It can cause vomiting, diarrhoea, anaemia, osteoporosis and inflammation of other body organs.

- Severity of symptoms vary from person to person. Some people can have symptoms after eating a tiny amount while others can eat a loaf of bread and not have symptoms but the gluten still affects their body

- Correct diagnosis is essential

- People with coeliac disease test positive to a blood antibody. A diagnosis is confirmed by a tissue biopsy. You must be still consuming gluten for these tests to be accurate

- You can also be tested for a gene. Between 40 and 50 per cent of the Australian population test positive to this gene. All people with coeliac disease test positive to this gene, but not all people who test positive have coeliac disease.

This article was originally published on ABC Science. View the original article.