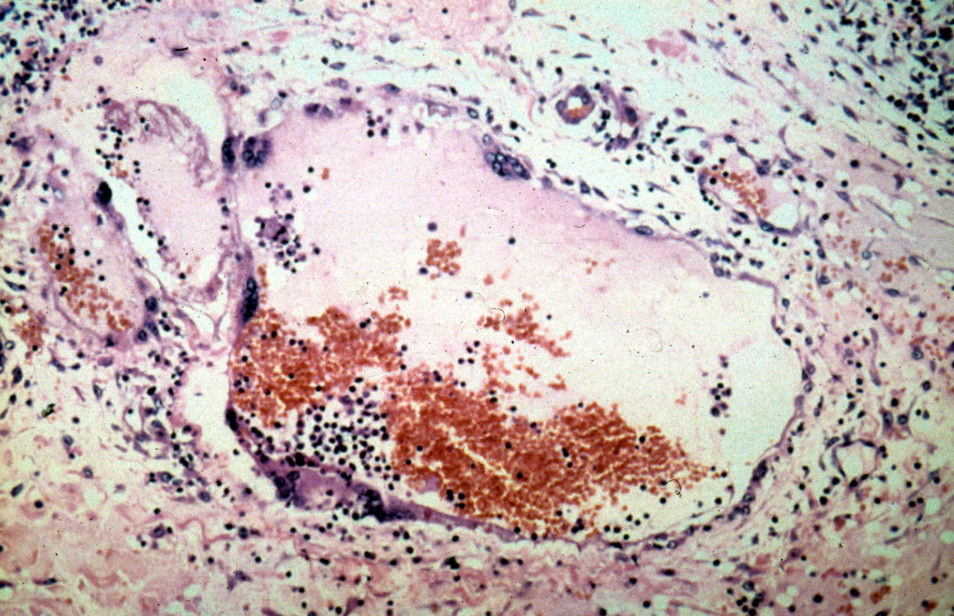

An oval shape with small red and black dots inside, in the middle of picture surrounded by a purple colour which is full of black spots and white irregular shapes.

Nipah virus under the microscope

Have you made the connection between climate change and its impact on human health? Then a new report released today is one you should read.

A report released today by the Global Health Alliance Australia states that “Australia and neighbouring countries in our region are experiencing more deaths, illnesses and injuries from heatwaves, cyclones and other extreme weather events because of climate change.”

Already, in the Asia Pacific region, climate change is raising sea levels. But it’s also exacerbating the severity of natural disasters, reducing nutrition levels in food and increasing disease produced by unclean water.

Australians are becoming increasingly vulnerable to climate-related health issues. This includes new infectious diseases, malnutrition and a rise in the number of deaths during sustained heatwaves.

Climate change and disease incidence

As global leaders in health and biosecurity, we understand the increased risk of new infectious diseases arriving in Australia. We’ve been researching the link between environmental and human health for some time. Now we’re preparing Australia and working with agencies across the Asia–Pacific region to minimise the impacts of disease spread.

An example of this is the incidence of disease spread by animals. In the past 20 years, a significant number of highly lethal viral diseases have emerged from bat species across the world. In Australia, these include Hendra virus and Australian bat lyssavirus while Nipah virus was first documented in Malaysia in 1998.

Nipah virus causes disease in pigs, horses and potentially other domestic animals. The disease can be fatal, particularly in humans, with an average case fatality rate of 75 per cent according to the World Health Organization. The total number of cases to date estimated to exceed 700.

Nipah has not been seen in Australia, but this could change.

Nipah virus causes disease in pigs, horses and potentially other domestic animals.

Habitat loss caused by deforestation, forest fires, and to droughts that may be linked to climate change can result in fruit bats moving into more densely populated areas in search of food and water, increasing the chance of transmission.

Modelling undertaken by the EcoHealth Alliance, a global organisation that researches the links between environmental, human and animal health shows that by 2050, Northern Australia will be increasingly at-risk of Nipah virus becoming established.

Clearly, the arrival of this deadly virus into Australia would be a devastating blow to us all.

Climate change is also predicted to increase the incidence of Q Fever, an endemic disease which can be transmitted between animals and humans. More than half of Australian cases occur in Queensland, where the incidence rate is around 3.5 cases per 100,000 persons every year.

Q fever is carried by a variety of wild and domesticated animals, including wallabies, kangaroos and bandicoots. As climate change degrades their habitat in Northern Queensland, these animals are pushing into urban and semi-urban areas in search of grazing lands, such as golf courses and large residential blocks around Townsville. Their presence increases the risk of transmission of this highly infectious pathogen, particularly amongst middle-aged and elderly people.

A woman in a fully enclosed white biohazard suit sitting in front of a microscope.

Our scientists are working on solutions to control and mitigate outbreaks of diseases.

World-leading science

Fortunately, our scientists are already working on solutions and developing the knowledge, tools and countermeasures to control and mitigate outbreaks of disease. The CSIRO Dangerous Pathogens Team and colleagues at AAHL Geelong have undertaken research with Nipah to determine how the virus is shed from infected animals.

Others at AAHL are studying bat ecology and the bat immune system to determine how viruses maintain themselves in bats and how these viruses ‘spillover’ into other animals and humans.

Our international team work closely with health authorities in neighbouring countries to enhance the region’s capacity for disease diagnosis and emergency outbreak response,

This important report highlights the need for continued research into the links between the environment and human health.

Research on zoonoses, diseases transmitted from animals to humans, is conducted at CSIRO’s AAHL, our national biocontainment laboratory. It is a purpose-built facility designed to allow scientific research into the most dangerous infectious agents in the world.

5th September 2019 at 10:29 am

Silver Cord Adventures – you’re assigning too much purpose to blind systems. The Earth isn’t trying to protect itself; life is attempting to thrive. Our efforts have come at a cost to biodiversity richness, however as we most out of the Holocene into a hotter climate, it will favour other species and new niches will also appear.

We need to anticipate these changes because they will open new avenues for viruses and bacteria to exploit, impacting on us directly and indirectly (for example, diseases that will impact food production).

The warmer world ahead is a different world than the one we knew. Our research and development now will determine the success of future populations.

13th August 2019 at 9:58 am

Earth’s biological controls are trying to protect her from human overpopulation. The non-biodegradable chemicals and contaminants that humans put into the environment to try and save their own lives over the lives of other beings’ doesn’t help the cause. Saying that, I worked for a scientist once who I overheard say there was “menial people”, so I suppose access to these contaminants will be limited to those are not menial (a very rare few, no doubt), thereby minimising their risk to the natural world. Planting trees might be a good alternative to the problem – but then maybe some terribly unfortunate person will cut down those trees because they don’t like the looks of them after starving possums eat from them, or some other selfless, deeply meaningful reason.