Armed with a camera, a lab and lots of patience, our researchers are on a scientific mission. They’re on Heron Island in the southern Great Barrier Reef to witness and learn from the annual coral spawning event.

But it’s a little different to what happens out in the wild.

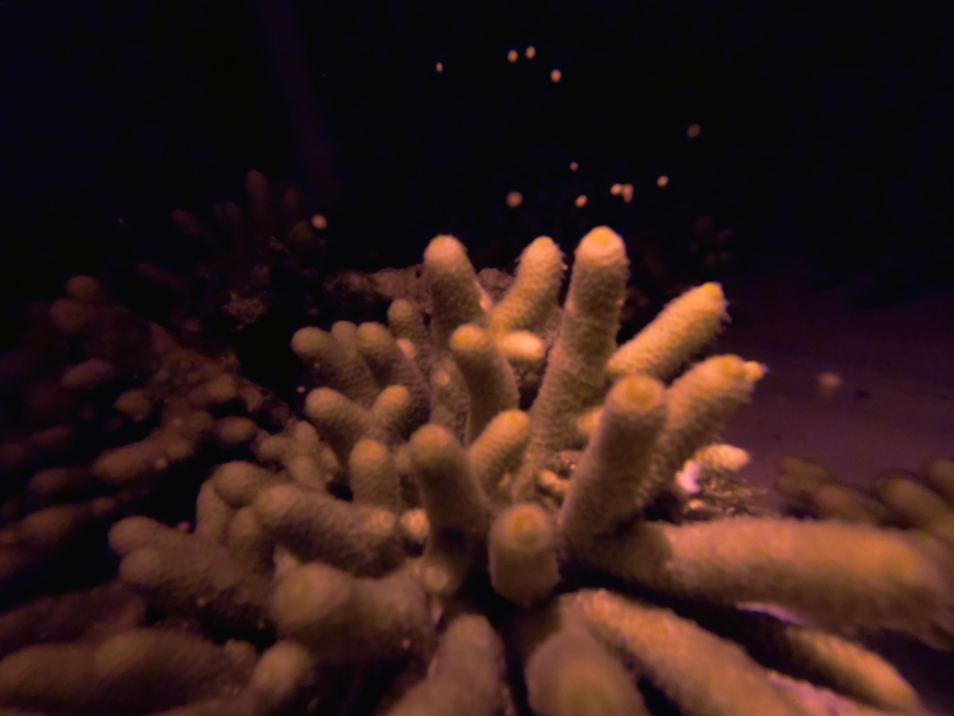

Ripe coral colonies ready to spawn – which is when they release egg and sperm bundles – are being collected from the reef and brought into the laboratory at the Heron Island Research Station. It’s here that our scientists are eagerly waiting for the corals to release their eggs.

Coral spawning usually only happens once a year after a full moon. Image: Christopher Doropoulos

Don’t stop us now: tracking coral eggs

Coral spawning typically only occurs once a year in the days following the November full moon. (Although remember this? In some instances, it can happen twice a year!)

We will be capturing millions of fertile eggs – each one the size of a pinhead – to aid their success in becoming new coral. This will help us develop techniques that will help restore parts of the reef. At a scale that could make a massive difference.

This builds on our coral spawning research out in the wild. Where last year we conducted a major field campaign to collect and culture wild coral spawn slicks. The operation was epic and a great success.

In collaboration with Van Oord – an international dredging and marine contractor – we built a 50,000-litre aquaculture system on a tug boat. This was to culture millions of coral larvae to help with reef restoration.

But don’t stop us now! We are building on our past success by taking the research into the lab. We will be developing ways to track coral larvae so we know where they go once they leave the aquaculture facilities.

Under pressure: how much pressure can coral larvae can handle?

We know how to collect, culture, and release wild coral larvae (known as spawn slicks). But we need to know how much stress coral larvae can handle. This way, we’ll know how to set future trial conditions for handling coral larvae for maximum positive impact.

We’re testing how turbulent conditions and water flow impact the larvae – from unfertilised eggs to fully competent swimming larvae ready to metamorphose onto the reef. Understanding these forces is essential so that we can use models to identify the ideal pressures for pumping larvae as we upscale this research.

We used a 50,000 litre aquaculture set-up to harvest coral slicks to help restore the Great Barrier Reef.

Aussie scientists supporting global reefs

There is a threat from human-driven disturbances to coral reefs throughout the world. This includes those found on the Australia’s Great Barrier Reef on the east coast and Ningaloo Reef on the west coast. Coral restoration is being conducted by leading organisations across Australia and all over the world, to kick-start coral recovery.

We are combining expertise in biology, ecology and marine engineering to scale up our efforts. This means restoration techniques will be more effective for larger areas and can be applied to reefs around the world. Not only will the corals be happier and more resilient. It aims to aid rehabilitation of marine life, food webs and healthy functioning of coral reefs too.

We are at Heron Island to witness the coral spawning event and to collect coral eggs to help aid Reef recovery. Credit: Lauren Hardiman

10th December 2019 at 9:36 am

I think support him /her in his work .

29th November 2019 at 7:33 pm

Thank God for our scientists!

28th November 2019 at 11:04 am

I am counting on you guys to do GREAT THINGS IN THE NEW YEAR…..full credit.