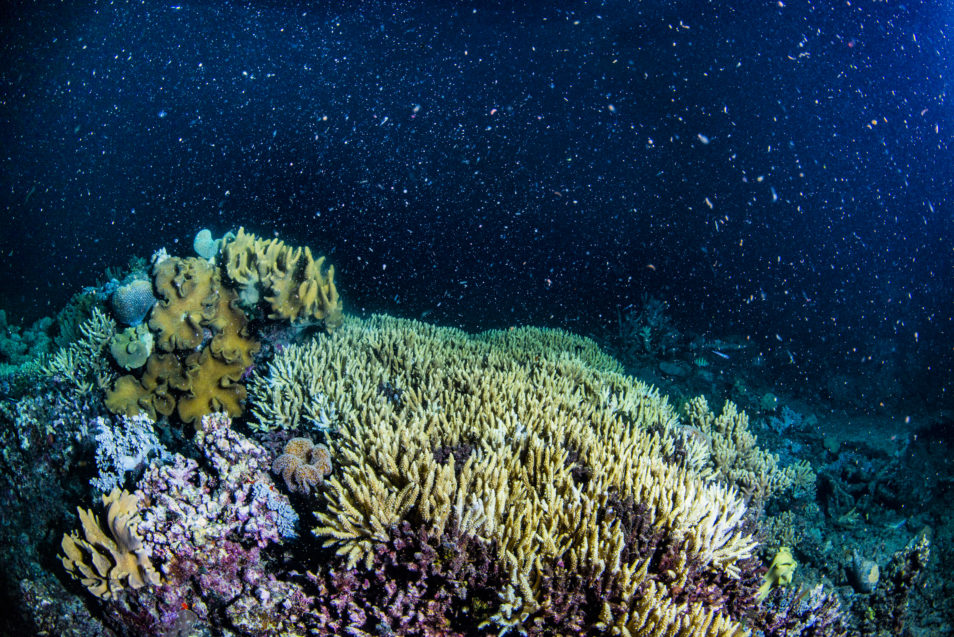

Coral spawning at night

Hard corals spawning captured by Queensland Museum’s photographer Gary Cranitch (taken for Great Barrier Reef Foundation) .

It’s been described as “the most spectacular events in our oceans.” And no, it’s not the gnarly waves you caught surfing on the weekend.

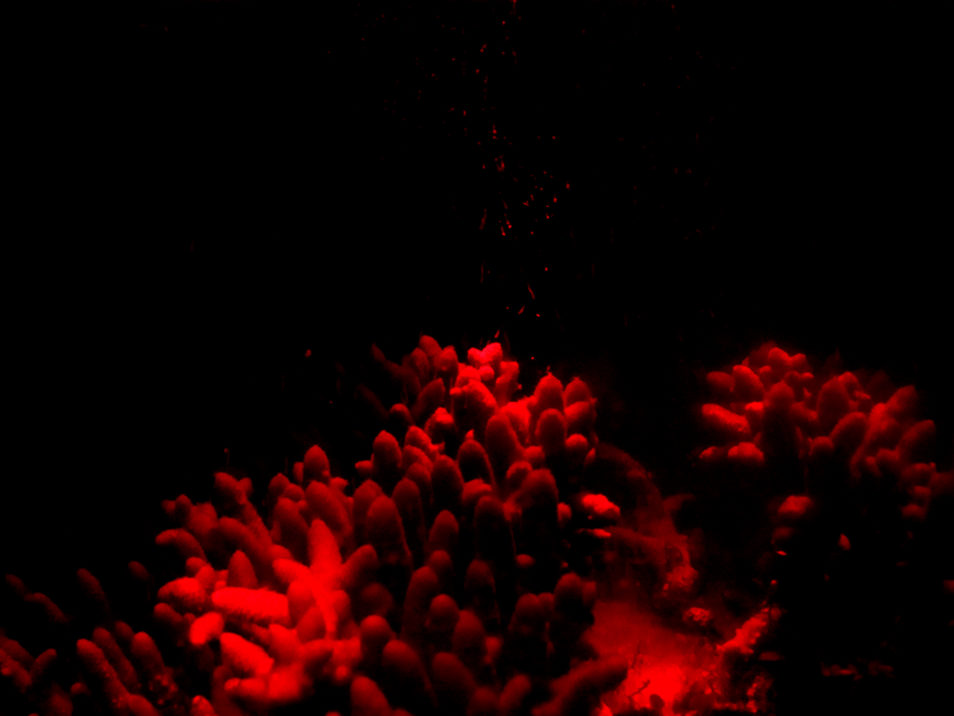

It’s coral spawning, which is when corals release tiny egg and sperm bundles into the water. It generally happens only once a year, after a full moon, for a few hours, over one to two nights.

But our scientists along with the University of Queensland have discovered something for the first time. When coral colonies spawn more than once a year, it can lead to better health for our coral reefs. The more larvae that set off into the water, the more chances they have to find new homes to help establish coral recovery. This even includes travelling to neighbouring reefs hundreds of kilometres away. This is good news for strengthening the resilience of the Great Barrier Reef.

Multiple coral spawning: Larvae in numbers

The corals that spawned over multiple months were successful in spreading their offspring across different parts of the Great Barrier Reef. This is exciting news for Dr Christopher Doropoulos, from our Oceans and Atmosphere team. He’s been studying coral spawning events, and what drives the successful recruitment of coral larvae, for the last 10 years.

“Spawning over successive months helps corals synchronise their reproduction to the best environmental conditions,” he said.

“Reproductive success during split spawning may be lower than usual, because it can lead to reduced fertilisation. But we found that the release of eggs in two separate smaller events gives the corals a second and improved chance of finding a new home reef. We call this ‘split spawning’ and it could help the coral communities of the Great Barrier Reef.”

Larvae larvae! Coral spawning is when coral release egg and sperm bundles into the water

Multi-skills for a mega-reef

To understand the impacts of this spawning, we applied modelling, coral biology, ecology, and oceanography. This meant we could simulate the dispersal of coral larvae during these split spawning events across the whole of the Great Barrier Reef. That’s more than 3800 individual reefs!

To do this we enlisted the expertise of our researchers Rebecca Gorton and Scott Condie, who have developed online tools such as eReefs and CONNIE. eReefs provides a picture of what is currently happening on the reef and what will likely happen in the future. CONNIE is used to calculate the movement and dispersal of almost any substance or planktonic organism in the ocean.

The team looked at whether the split spawning events were more reliable at supplying larvae to the reefs. They also looked at whether connectivity (the ability to exchange larvae) among the reefs was improving.

About last night: corals release egg and sperm bundles into the water, at the same time! They can then be fertilised and will turn into larvae.

Reef recovery and resilience

The results showed an increase in diversity of larvae, and better reliability for the larvae to reach different areas of the Reef.

These findings explain the higher chances of recovery for reefs in the region during split-spawning years. The extra spawning events provide a more robust supply of coral larvae to reefs. This is particularly important for areas of the reef that have suffered disturbances, such as coral bleaching and unpredictable environmental conditions.

The Great Barrier Reef providing ecosystem services worth more than $6 billion per year in Australia alone. So, this research highlights the importance of coral recovery to sustainably manage the Reef.

This research was published in Nature Communications and was a collaborative project with University of Queensland and the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies.

Did you know that the Great Barrier Reef is made up of more than 3,800 coral reefs? New research on coral spawning could help coral health, particularly in areas that have suffered coral disturbances. Credit: Shella Dee

14th August 2019 at 8:14 pm

Interesting, useful and encouraging research. Can this knowledge help us to artificially create conditions to produce extra spawning events to help the reef regenerate more quickly?

15th August 2019 at 10:37 am

Hi Maria,

Mass coral-spawning events occur at the scale of the entire Great Barrier Reef – approximately 340,000 km2. All of the corals found on these reefs have their reproductive cycle finely tuned to local environmental conditions so that they release their eggs and sperm when conditions are ideal to enhance their survival and optimise development into new coral colonies. Even if it was technically possible to manipulate something like the temperature of the water for the nine months it takes corals to develop their reproductive cells at such a massive scale to try and control split-spawning events, the repercussions of such a massive manipulation would be far too risky to attempt for all the other processes going on the reef. For example, it may increase the possibility of coral bleaching. So in this case, it’s best to leave the corals alone and let them align their reproductive cycles as they have done throughout evolutionary history to maximise larval supply and reef recovery.

However, there are quite a few other initiatives attempting to try and scale-up coral restoration efforts – some of which we have been trialling here at CSIRO https://blog.csiro.au/coral-harvesting-helps-restore-great-barrier-reef/. There is a lot of work focussing on scaling-up and optimising coral restoration on the Great Barrier Reef, in an initiative called the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program. You can read about it here: https://www.csiro.au/en/Research/OandA/Areas/Coastal-management/Reef-capability/Reef-restoration-program and https://www.gbrrestoration.org/