It only happens once a year, for a few hours, over one or two nights.

It’s not how often you use your gym membership. And it’s not another one of Johnny Farnham’s ‘Last Time’ tours …

It’s a coral spawning event! And our scientists are using this spawn to help restore coral on the Great Barrier Reef.

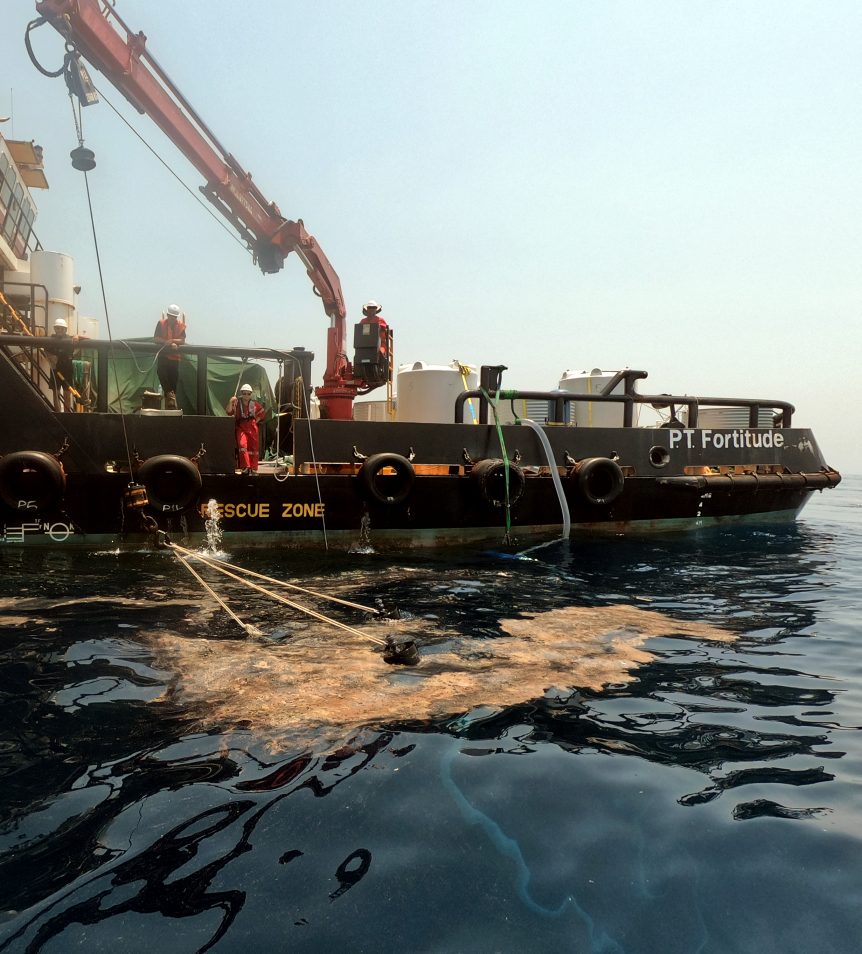

It’s harvest time: Our scientists are collecting coral spawn (the pink floating bits!) to restore damaged parts of the Great Barrier Reef.

A big reef needs big ideas

Coral spawn their egg and sperm bundles (which form larvae) over a very short window of time. The bundles float on the surface of the water, and join together in a giant armada, forming extensive ‘slicks’ that can be kilometres long.

The spawning might only happen once a year, so we are very happy when we find a coral spawn slick. Why? Because we’re harvesting coral larvae to help restore coral.

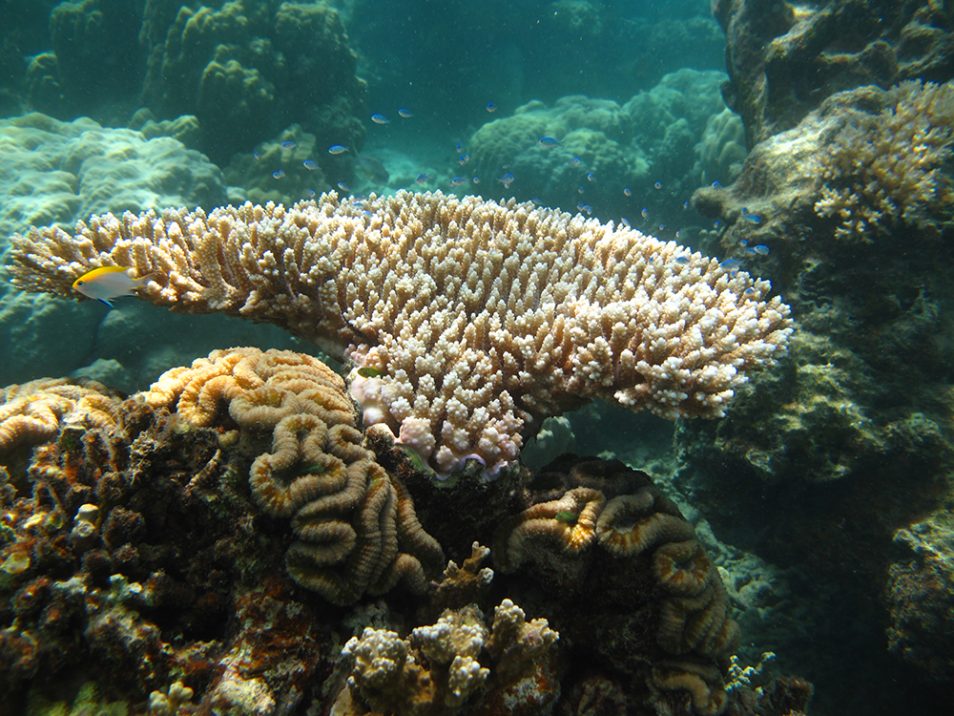

Coral bleaching, crown-of-thorns starfish and cyclones have damaged the Great Barrier Reef. So we need big solutions to help the reef— after all, the Great Barrier Reef is equivalent to the size of Italy! We need to restore and safeguard coral across the whole Reef, not just localised areas.

Our scientists are meeting this challenge through trialling an industrial scale coral restoration approach, and the early signs are good. We’re doing this through our Recovery of Reefs Using Industrial Techniques (RECRUIT) project.

We’re pumped about coral slicks

Harvesting coral larvae slicks is an industrial affair. We use a well-equipped tug boat and a fully-fledged, 50,000 litre on-board aquaculture set-up.

The slicks are pumped onto the vessel into massive culturing tanks. Scientists then test the density of live embryos and larvae, and how well they will survive. So far, results have shown that the density of live embryos in the slicks are thousands of times greater than ever recorded.

Once they’re on board, the embryos are left to develop into larvae in the culturing tanks. After just five days, the larvae are older and more robust, and ready to transition from larvae into tiny coral polyps.

We have an impressive 50,000 litre on-board aquaculture set-up, ready to grow and nuture the spawn into strong little larvae.

We can use this technology to send coral larvae to parts of the Reef that have suffered major damage and don’t have a natural supply of new larvae coming in. Once the larvae are released onto the reef and metamorphose into tiny coral polyps, they make their skeletons and grow to form new and healthy coral colonies.

Our new method of collecting coral spawn slicks means that we can transport larvae anywhere across the Reef, far from their original spawning sites. For example, larvae in one part of the Reef can be sent north, or south, depending on where bleaching has occurred.

And the results so far are very promising.

Millions of larvae on the horizon

Our research shows that there’s great potential to achieve large-scale restoration of coral with this low-impact technology.

The next stage of this project aims to upscale the approach even further. We want to apply large scale restoration and provide half a billion larvae to areas of the Reef needing restoration. This may sound like a lot of larvae, but it’s still a small fraction of the total number of larvae found across the Reef.

The Great Barrier Reef isn’t just a natural beauty. It supports industries such as fisheries and tourism, worth more than $6 billion per year in Australia. So this research is great news for the ongoing management of the Reef and all the people who depend upon it.

We are doing this research with our industry partner Van Oord Dredging and Marine Contractors, and Delft University. Funding was provided through an Advance Queensland Small Business Innovation Research grant.

It’s an industrial affair: once a slick is located, pumps are used to collect the coral embryo on board.

Relocating coral larvae could be one of the keys to helping restore the Great Barrier Reef from coral bleaching, as shown here.

26th June 2020 at 3:59 pm

I seem to remember there was research being done in Australia to cultivate and encourage more temprature-tolerant strains of algae to inhabit reefs. Has this proved useful?

30th June 2020 at 3:53 pm

Hi Robert, I’d suggest checking this blog out on our work to develop heat-resistant coral: https://blog.csiro.au/heat-resistant-coral/

Thanks,

Georgia

Team CSIRO

16th February 2019 at 6:42 pm

I’d lie to see cool water from the deep brought up to cool the water around the Reef. Brian Von Herzen found bleached coral had recovered its colour within a day of bringing up the cool water from the deep.