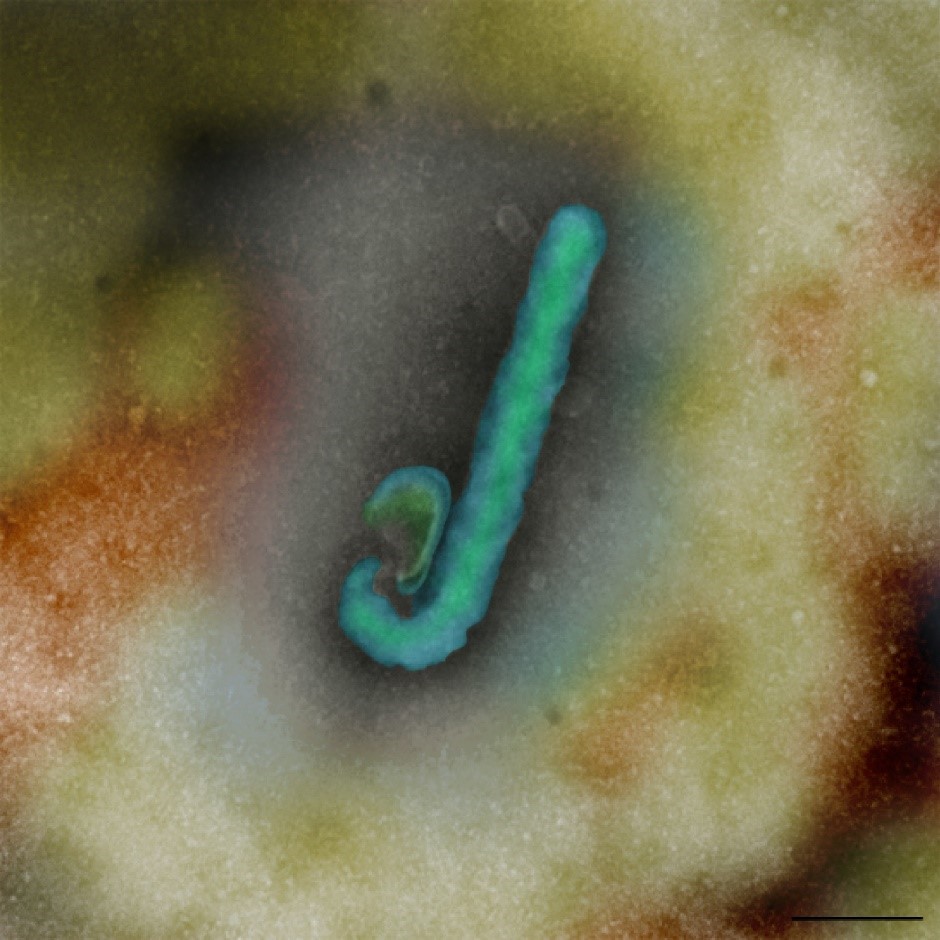

A microscopically enlarged image of the Ebola virus

An artificially coloured electron microscope image of the Ebola virus

The World Health Organization has declared Ebola a ‘Public Health Emergency of International Concern’ (PHEIC), for the second time in five years. So, how can the global public health community better support relief efforts in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)?

Current situation with Ebola in the Democratic Republic of Congo

The last major African outbreak mainly affected Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea, with 28,646 cases and a 40 per cent mortality rate. This epidemic killed five times more people than all other known Ebola outbreaks combined. And a PHEIC was declared between 8 March 2014 and 29 March 2016.

After sporadic outbreaks in 2017 and 2018, the DRC is now experiencing the world’s second-largest recorded outbreak. As of 5 August 2019, 3150 people have infected with a 59 per cent mortality rate. Reports out of the region suggest that only half of the cases are being identified and reported. Most of them in the region of Kivu.

The disease has also spread to neighbouring Uganda and been reported in places close to the DRC’s border with Rwanda and South Sudan.

The decision to declare a PHEIC is a complex one. It involves weighing potential effects on travel and trade that could impede support to affected regions and hinder outbreak control, as argued by the World Health Organisation (WHO).

What can developed countries do?

The outbreak cannot be solved just with more funding and medical expertise that will arrive thanks to the PHEIC declaration.

First and foremost, we need to listen to the local leadership and ask them what they need for a community-led response. And not assume what they want.

The DRC Ministry of Health had asked for “more cohesion, more harmonization between the different interventions, [and] more alignment with the strategic plan of the Ministry of Health.” Lot of us want to help but are unsure how. So, we need more coordination to ensure each of us is focusing on our core competencies to address needs on the ground.

Secondly, we need to take on board the valuable and transferable lessons from the last outbreak. This includes dialogue and delicate compromise with the community to ensure safe burial practices.

Similar to the sustainable Resilient Zero program in Sierra Leone, we should strengthen their district health capacity, laboratory network and disease surveillance systems. We can then detect and respond effectively to not just Ebola, but also other infectious diseases.

Thirdly, vaccination alone cannot solve Ebola. This is due to a range of factors including lack of 100 per cent protection, adverse effects, clinical and other challenges around coverage, compliance and cost-effectiveness. That is why the global scientific community needs to accelerate the development of treatments that complement the two experimental Ebola vaccines currently in use.

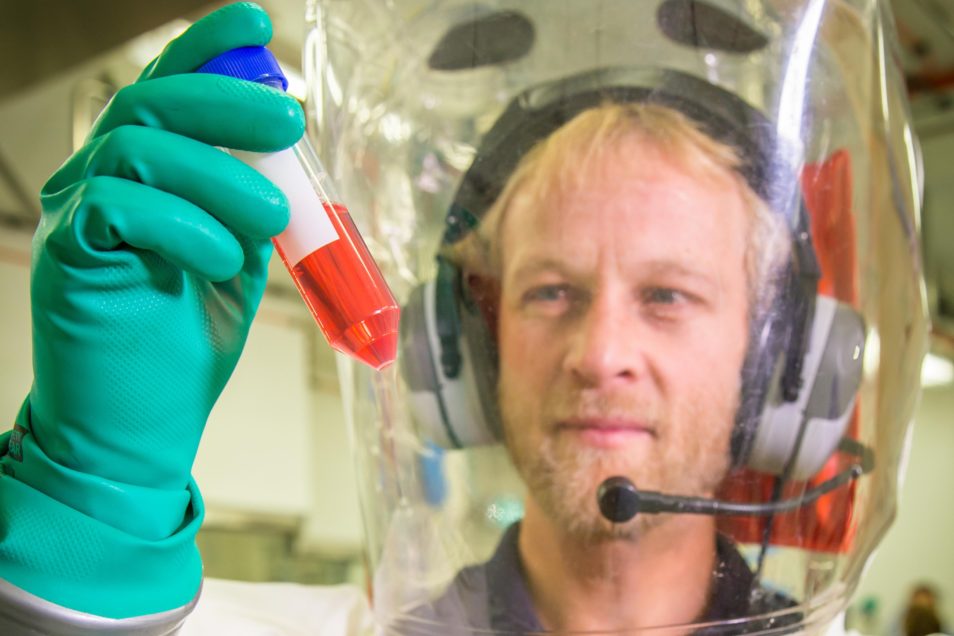

Promising novel and repurposed drugs and treatments need to be evaluated in appropriate animal models in laboratories operating under the highest containment (‘Biosafety Level 4’). But such high secure facilities, like our own Australian Animal Health Laboratory (AAHL), are very few in number. So, we need greater coordination to ensure there is no duplication of efforts. Some mechanisms are already in place, such as the BSL4ZNet, an international network of laboratories like AAHL to protect against animal to human disease. And the fast track model agreement for rapid collaboration, which shares results for a global coordinated response.

A man dressed in a fully enclosed biosecurity protective outfit holding up and examining a test tube containing red liquid

A CSIRO infectious disease researcher working in the CSIRO high containment lab

Looking long-term beyond outbreak response

Recently there has been a greater risk of infectious diseases being transmitted to people from wild and domesticated animals. This is due to growth and geographic expansion of human populations and the increase in agricultural practices. Increased global travel also means there is a greater likelihood that infectious agents, particularly airborne pathogens that can produce disease, can rapidly spread among the human population. Together, these factors have increased the risk of pandemics. It’s not so much a matter of if, but when. While the current list of known emerging infectious diseases is a major concern, it’s the unknown viruses, with a potential for efficient human-to-human transmission that pose the biggest threat.

Ebola and other haemorrhagic fever viruses are likely to re-emerge and pose a great threat to health and biosecurity. Especially in Africa and other developing nations. These settings have a relatively low health expenditure, high likelihood of such outbreaks, and an urgent need for rapid, safe, cheap and effective treatment options. Therefore, the typical 17 years’ ‘implementation gap’ in the health research translation process is simply not an option for Ebola and similar diseases.

Ebola has increased the ‘intersectionality’ of suffering among the 13 million people living in a complex humanitarian crisis in the DRC. This includes ongoing conflict and widening health, wealth and gender inequalities. To solve this, we need a strong and locally-led social science and humanitarian focus. This would help guide scientific research, development, evaluation and uptake of response strategies and promising medical countermeasures. For the long-term, we need to focus on planning, preparedness and resilience, not just outbreak response.

10th August 2019 at 3:06 am

Interesting read and great use of image.