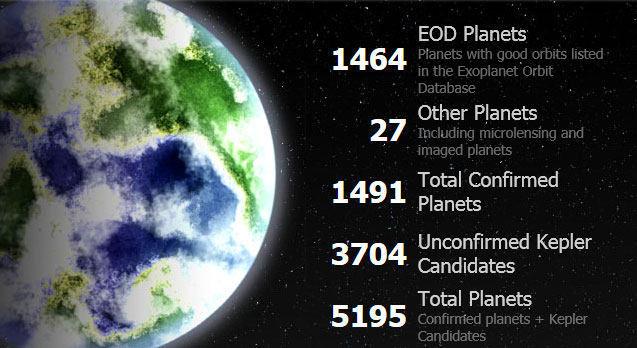

Worlds discovered to date. Image: exoplanets.org

It seems that nearly every week there is another announcement of a new planet being discovered somewhere – out there! Most are gas giants, some are smaller rocky worlds. Most are in close orbits to their stars while a handful sit in the so-called “Goldilocks” or “habitable” zone.

These planets follow the “rules” of planetary formation models, but then there are some worlds that break those rules.

One recent announcement for a new ‘exoplanet’ (planets that orbit stars in other solar systems) was the discovery of a large ‘rocky’ world that is estimated to be more than twice the size of the Earth. Nothing unusual in that.

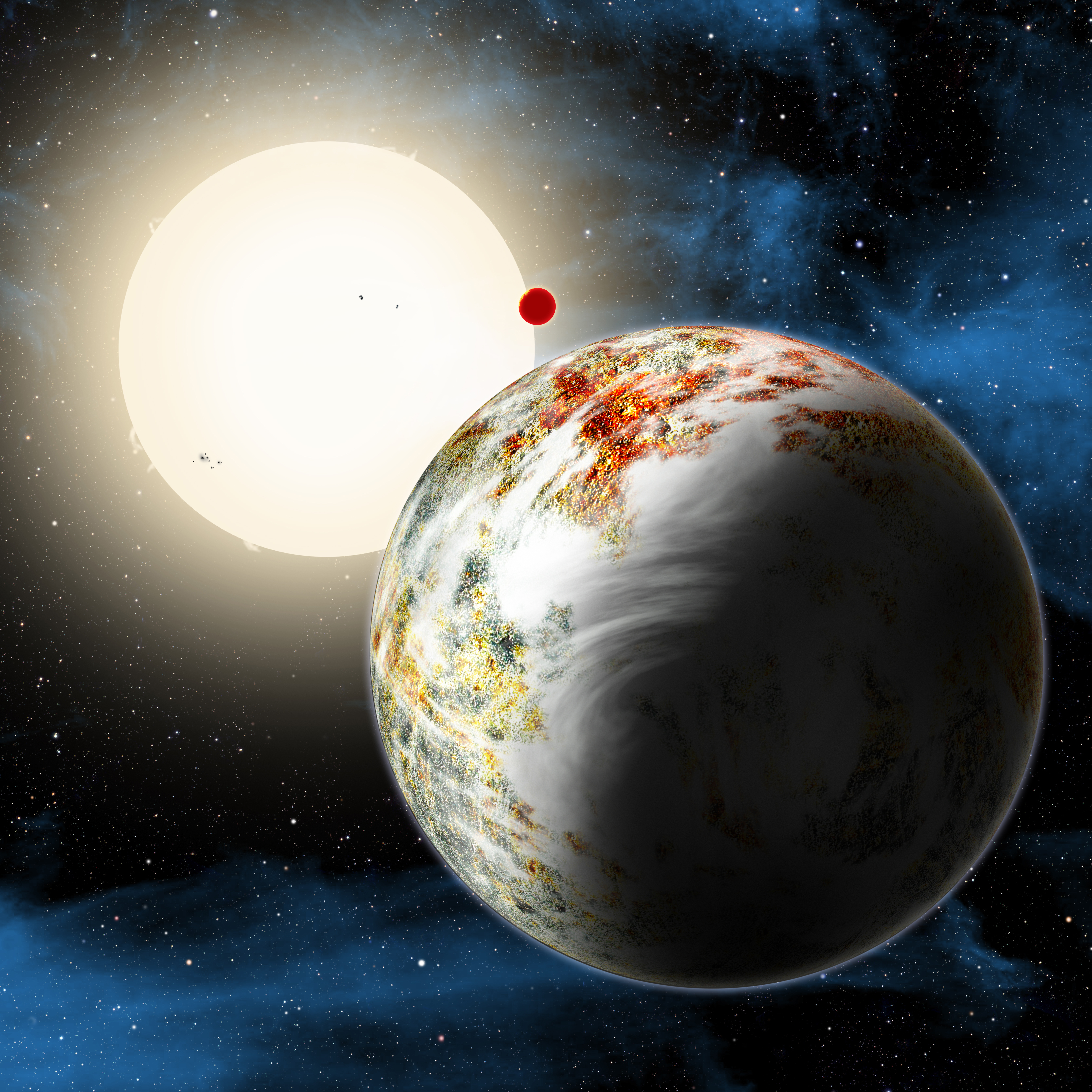

An artist concept shows the Kepler-10 system, home to two rocky planets. In the foreground is Kepler-10c, a planet that weighs 17 times as much as Earth and is more than twice as large in size. Image: NASA

Designated Kepler-10c, the planet though has scientists a bit mystified because their calculations show that its mass is 17 times more than that of the Earth. A planet of that mass should gravitationally attract an envelope of gases around it to form a much larger, perhaps ‘Neptune-sized’ world or larger, but Kepler-10c is just this massive rock in space.

Orbiting its star every 45 days, temperatures on the sun-facing side would make it a place too hot to support life. Located 560 light-years from Earth in the constellation Draco, astronomers are at a loss to figure out how the planet would have formed without turning into a gas giant.

This isn’t the only mystery world however.

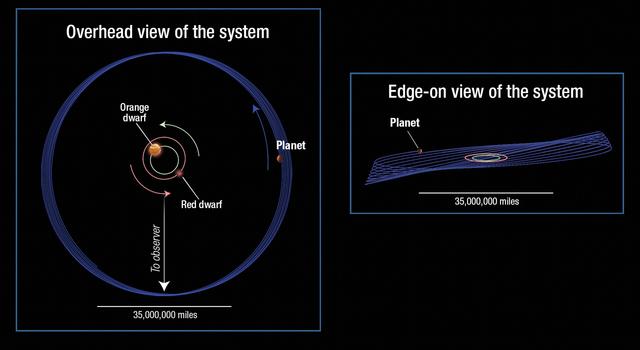

The rollercoaster orbit of planet Kepler-413b. Image: NASA and ESA

Tucked away in the Cygnus constellation about 2,300 light years from Earth, the planet Kepler-413b is literally on a wild amusement park ride. The planet’s 66 day orbit is like a rollercoaster, travelling in a wave-like pattern around its parent stars, a pair of orange and red dwarfs. The planet also wobbles on its axis up to 30 degrees over only an 11 year period, compared to the Earth which wobbles on its axis over 26,000 years.

Astronomers think that the gravitational influence of other planets in this solar system or possibly a third nearby star may be exerting an influence.

Kepler-413b is a Neptune-sized world, 65 times the mass of the Earth. Due to its close but erratic orbit to the binary stars, temperatures would most likely be too hot to allow liquid water to exist making the planet an unlikely candidate for supporting life as we know it.

At the other end of the scale is a world so far away from its sun-like star that is should be nothing more than a frozen ball of rock and ice. Planet HD 106906b however is a gas giant world, 11 times the mass of Jupiter.

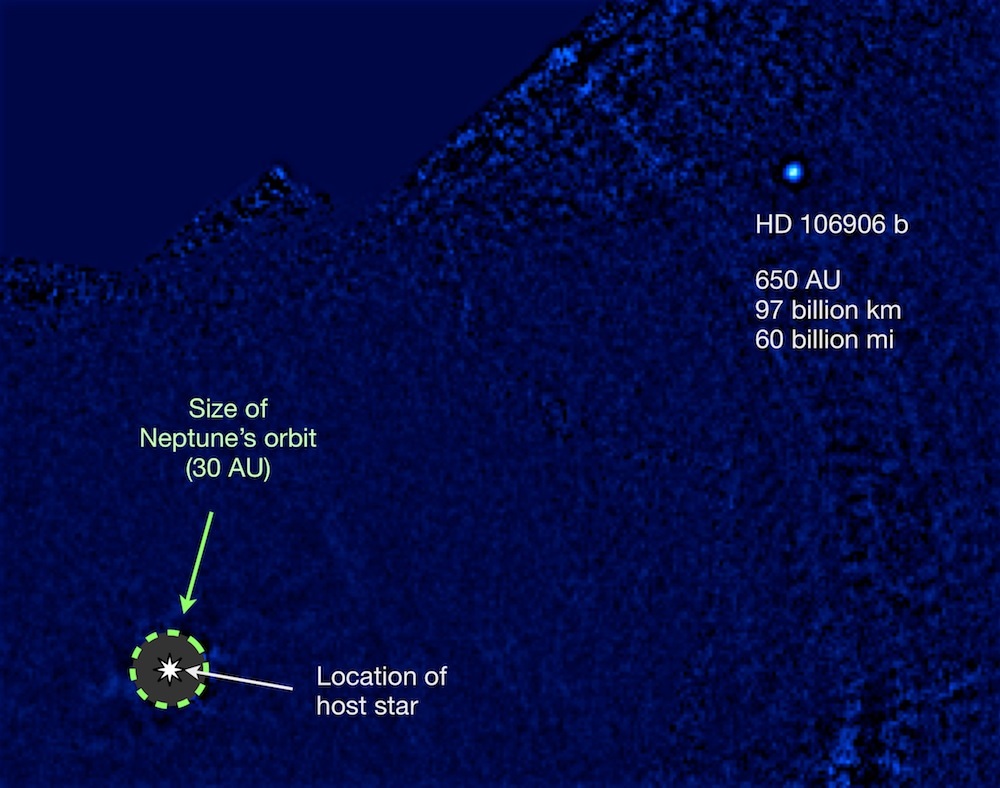

Processed image depicting the relative distances of Neptune’s orbit compared to HD 106906b from its parent star. Image: NASA

The planet is challenging planetary formation models. At a distance over 20 times further away from its star than Neptune is from our sun, HD 106906b is only a relatively young world at around 13 million years old.

Detected by its infrared signature, HD 106906b is still quite hot at 1,500 degrees Celsius due to the residual heat from its formation. The mystery is how such a planet could have formed so far away from the star it is orbiting and the disk of dusty and rocky material surrounding that star where planets would normally coalesce.

It’s possible that the planet may have formed in a completely separate cloud of material around another nearby but failed star. As its new parent star travelled through the galaxy it was caught by its gravity in a sort of celestial adoption process.

Then there are those planets that are orphans.

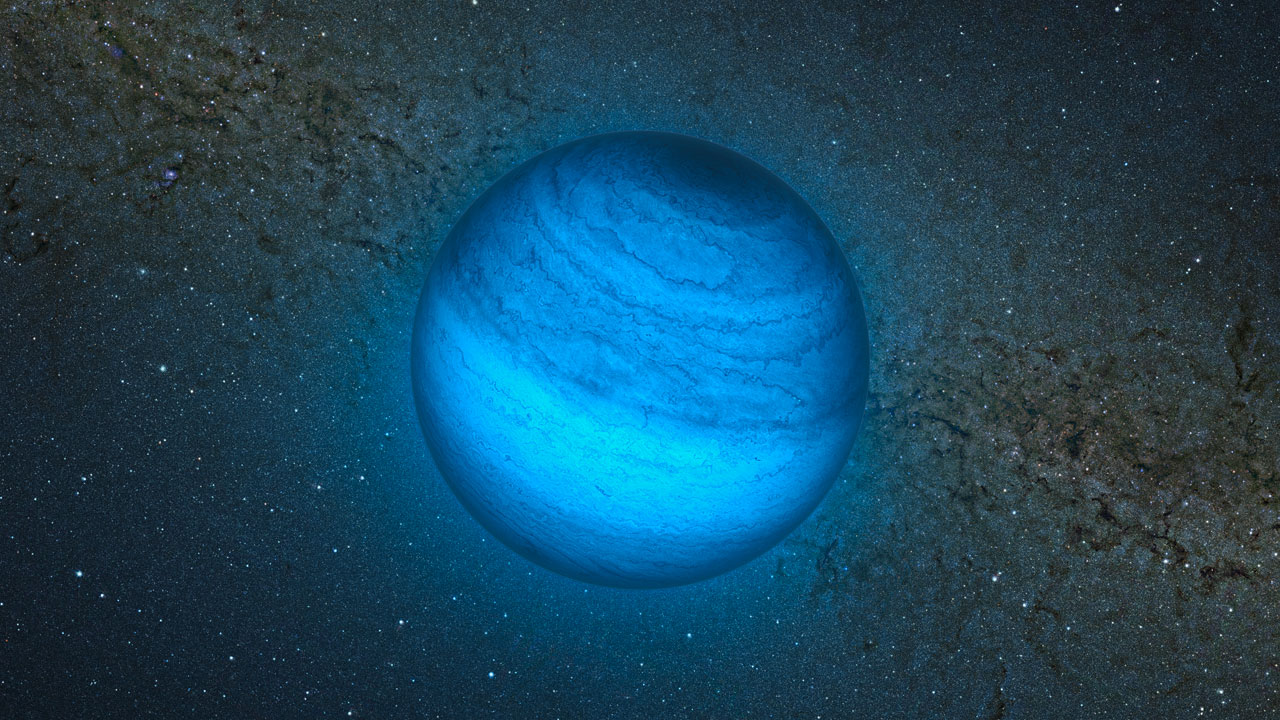

This artist’s impression shows the free-floating planet CFBDSIR J214947.2-040308.9. This is the closest such object to the Solar System. It does not orbit a star and hence does not shine by reflected light; the faint glow it emits can only be detected in infrared light. Here we see an artist’s impression of an infrared view of the object with an image of the central parts of the Milky Way from the VISTA infrared survey telescope in the background. The object appears blueish in this near-infrared view because much of the light at longer infrared wavelengths is absorbed by methane and other molecules in the planet's atmosphere. In visible light the object is so cool that it would only shine dimly with a deep red colour when seen close-up.

Artist’s impression of the free-floating planet CFBDSIR J214947.2-040308.9v Image: ESO

CFBDSIR2149 is a free-floating planet seemingly with no nearby star. Around four to seven times the mass of Jupiter, the planet is 100 light years from Earth and appears to be travelling through the galaxy in parallel with the AB Doradus star cluster.

Free-floating objects like CFBDSIR2149 are thought to form either as normal planets that have been booted out of their home systems, or as lone objects like the smallest stars or brown dwarfs.

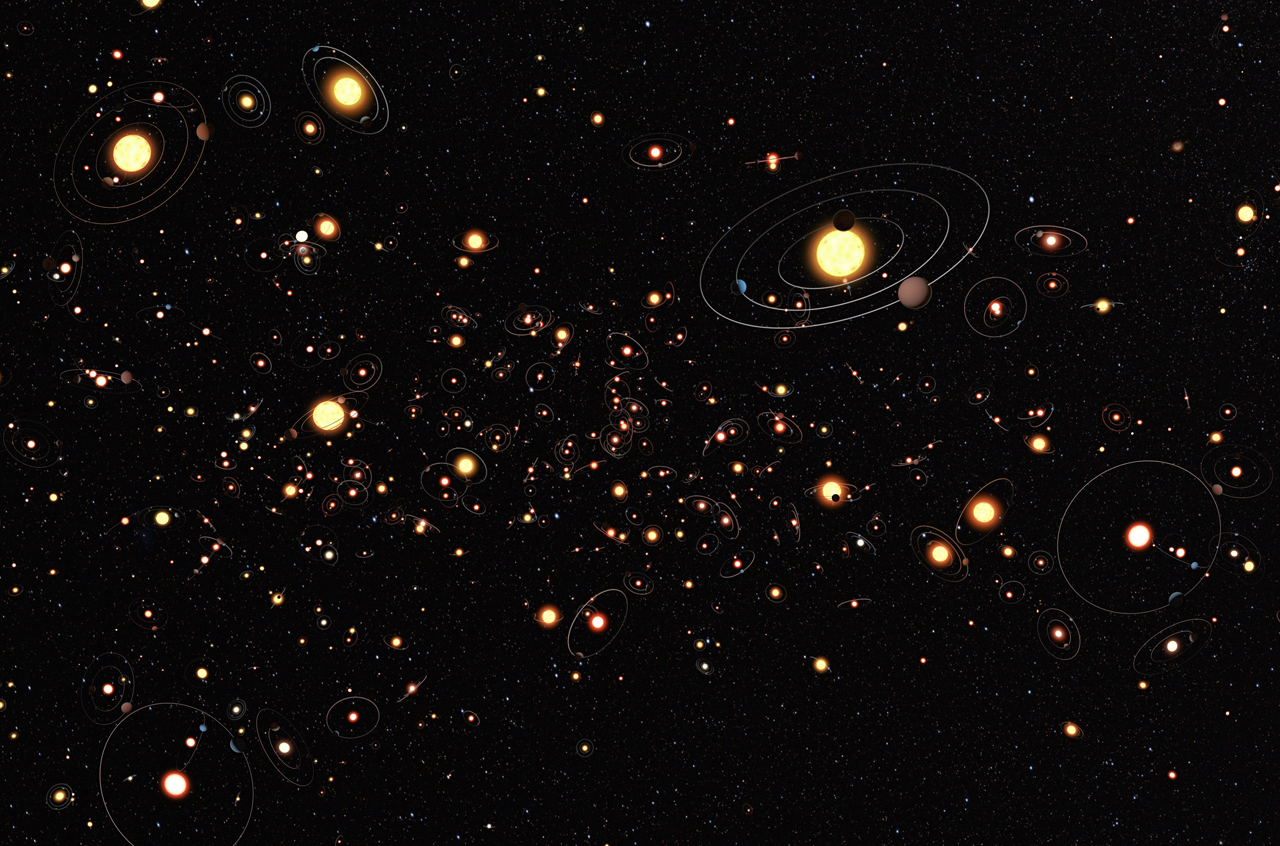

This artists’s cartoon view gives an impression of how common planets are around the stars in the Milky Way. The planets, their orbits and their host stars are all vastly magnified compared to their real separations. A six-year search that surveyed millions of stars using the microlensing technique concluded that planets around stars are the rule rather than the exception. The average number of planets per star is greater than one.

Artists’s cartoon view gives an impression of how common planets are around the stars in the Milky Way. Image: ESO/M. Kornmesser

These are a handful of examples of the planets that don’t quite fit the scientific models out of the multitude of solar system that have been discovered so far.

Surveys suggest that there could be as many as a trillion planets in our galaxy, actually outnumbering the stars in the Milky Way. Just based on what has been found so far, there are likely to be many more weird, wonderful and mysterious worlds out there just waiting to be discovered.