African swine fever is closer to our doorstep than ever before. But we’re working to stop it.

Update April 2021: Testing again detects African swine fever (ASF) in seized pork products

Since this blog was first published in October 2019, ASF has continued to spread throughout Southeast Asia and the Pacific. In late March 2020, Papua New Guinea officially notified the World Animal Health Organisation of ASF outbreaks in the Southern Highlands province.

In April 2020, our scientists confirmed samples received from PNG were positive for the ASF virus. In response, our staff expanded their work in an Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) project in PNG, to include building diagnostic testing capability for ASF.

ACDP has also continued to support the PNG National Agriculture and Quarantine Inspection Authority with diagnostic testing for outbreak response and surveillance activities. ASF has now been identified in six highland provinces.

Our scientists at ACDP also continue to support the Australian government’s biosecurity response, conducting tests on samples from seized imported pork products in 2021. We again detected fragments of the ASF virus in some of these seized products. Read the latest news from the Australian Government.

About African swine fever (ASF)

African swine fever (ASF) is a fatal pig disease. And it’s on Australia’s doorstep with confirmation of outbreaks in Timor-Leste, 680 kilometres from northern Australia.

The disease is found in sub-Saharan Africa and has been detected in countries in Eastern Europe, including Russia and Ukraine. This year we have seen the disease sweep down through Asia and towards Australia.

ASF kills about 80 per cent of the pigs it infects and there is no vaccine or cure. Some estimate a quarter of the world’s pigs will be dead by the end of this year from ASF.

We can’t understate the consequences as pork and other red meat prices are already seeing an increase in Europe and Asia. There is also talk of a global protein shortage for 2020 as a result of ASF.

Australia, which has a $5.3 billion pork industry and 2700 producers, continues to be free from the disease. We’re working with the Australian government and industry to keep it that way.

ASF on our doorstep

The Department of Agriculture has implemented tight biosecurity measures. This maintains strict controls over imported products which could be contaminated with the ASF virus. It also has heightened surveillance and increased screening for banned pork products.

Recently, Australia deported a Vietnamese tourist after border force officials found 10 kilograms of banned food products in her luggage. This included a large amount of raw pork. She was the first tourist to have her visa cancelled and be expelled from the country over breached biosecurity laws.

In September 2019, researchers at our Australian Centre for Disease Preparedness (ACDP) (formerly the Australian Animal Health Laboratory AAHL) tested pork products, seized at international airports and at international mail processing centres, for ASF virus. ACDP is Australia’s leading high-containment laboratory for exotic and emerging animal diseases. It has unique facilities and expertise to manage the biosecurity risks of testing samples for the virus.

The results from ACDP’s testing last month showed 48 per cent of seized products were contaminated with ASF virus fragments. This is an increase from 15 per cent in the testing ACDP undertook earlier this year.

Detection of these virus fragments does not necessarily mean they can cause infection. But it does highlight the need for Australia’s strict biosecurity measures. Authorities are now using these results to refine and strengthen Australia’s border measures.

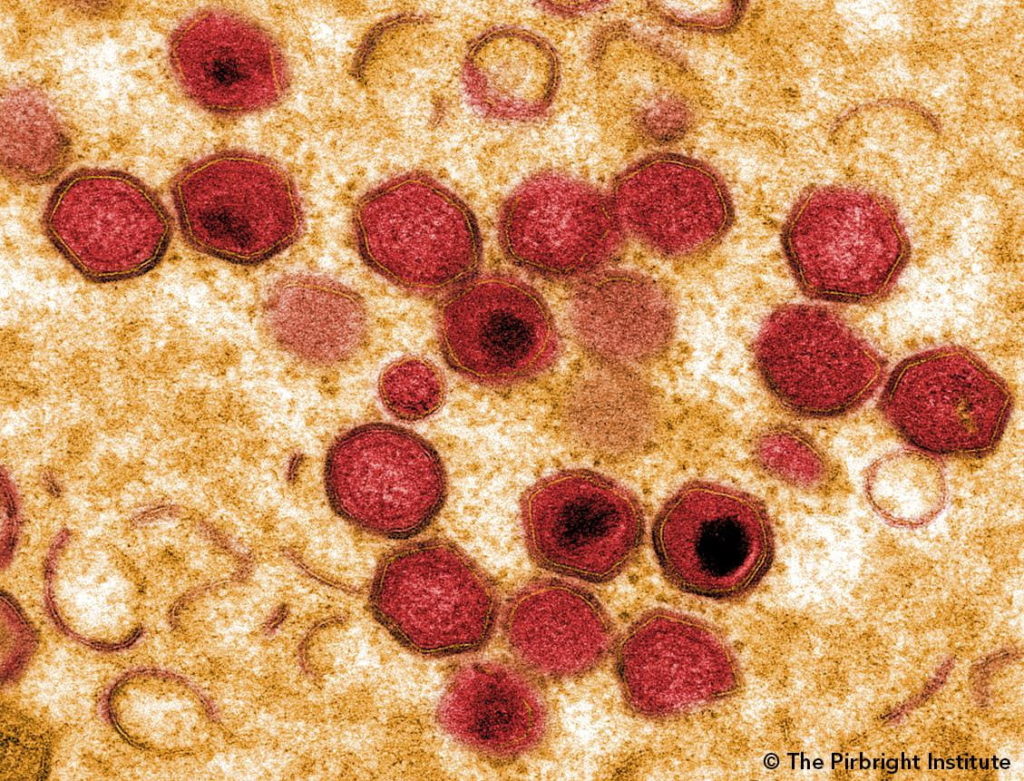

African swine fever under the microscope. Image credit: The Pirbright Institute

ASF is harmless for humans but spreads rapidly

ASF is harmless for humans but spreads rapidly among domestic pigs and wild boars through direct contact or exposure to contaminated feed and water. For instance, farmers can unwittingly carry the virus on their shoes, clothing, vehicles, and machinery. It can survive in fresh and processed pork products. It is even resistant to some disinfectants.

With no vaccine available, controlling the spread of the virus can be difficult. This is especially so in countries dominated by small-scale farmers who may lack the necessary resources and expertise to protect their herds.

For example, swill feeding—giving pigs kitchen and table waste in which the virus can persist—is a common practice throughout Asia. This is a major factor contributing to the spread of ASF. Unfortunately, it’s difficult to enforce a ban on this practice. Especially across so many small holder farms in resource-poor countries affected by the disease.

But action is being taken.

Our domestic biosecurity network

We are all working together to manage surveillance and monitoring as the risk of ASF entering Australia is on the rise.

In addition to testing, we continue to strengthen our national biosecurity network. We’re working with quarantine services, agriculture and human health organisations to build awareness, assessment, resilience, preparedness and response.

Our researchers are working on understanding how ASF virus infects pigs as well as looking at novel approaches to producing a vaccine. With no vaccine currently available, outbreaks of ASF are difficult and costly to contain and eradicate.

In the policy space, a round table meeting at Parliament House was recently held. Along with other leaders, scientists and governments, we shared the work currently being undertaken and the actions needed to keep ASF out of Australia.

Plans are underway for a simulation exercise later this year. This will test Australia’s disease response capabilities to make sure we’re as prepared as we can be.

The Australian Centre for Disease Preparedness (formerly the Australian Animal Health Laboratory), is on the case.

Helping our international neighbours

ACDP has an important role to play in the Asia-Pacific region. Our international team work with partner agencies and Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade to provide expertise, training and laboratory skills to rapidly identify disease.

This support enhances the region’s capacity to manage emergency disease outbreaks. It also assists our own pre-border security through better threat assessment and management of viruses circulating in neighbouring countries.

We also provide regional expertise to the World Organisation for Animal Health and the Food and Agriculture Organization (a specialised agency of the United Nations) for emergency preparedness missions to the number of countries at risk of virus.

We can all help

Fortunately, Australia’s pig industry is better equipped to manage the necessary biosecurity measures. And producers are willing to put strict controls in place to keep the disease at bay. Hobby farmers must also be careful to follow the rules.

None of us want to see images of dying pigs and farmers struggling to make ends meet on our screens. We can all play a role in good biosecurity.

Be aware of the risks and, most importantly, please don’t import illegal meat products or feed pigs with food scraps.

For further information, visit the Department of Agriculture’s information on keeping African swine fever and foot-and-mouth disease out of Australia.

5th November 2019 at 5:17 am

24 million feral pigs in Australia. If the federal government does not act before May 2020, zoot alore.