New Zealand’s weta insects are the stuff of legend: portrayed by Hollywood as huge, spiky man-eaters attacking King Kong explorers in faraway lands (well, as seen below in the 2005 version at least… WARNING: Terrible acting!):

In reality, weta are a little less fantastic than their popular culture portrayal – but that’s not to say they don’t still hold a few surprises of their own. They are indeed big: some weta species are among the largest and heaviest insects in the world. And while they are technically vegetarian, their large mandibles have been known to deliver an aggressive and painful bite to wayward humans.

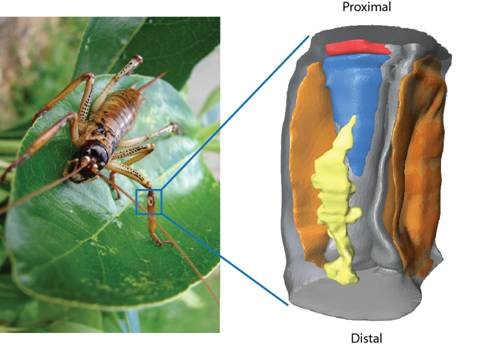

A New Zealand tree weta: holder of many surprises.

But perhaps most surprisingly, weta may hold the key to developing better hearing aids.

Yes, you heard correctly! It turns out that a unique lipid – a fatty waxy material found in the ears of the weta – may hold the key to better hearing for us humans.

One of our postdoctoral fellows, Kate Lomas, studied the hearing of the New Zealand tree weta (Hemideina thoracica) at the University of Auckland, discovering the unusual lipid and finding that it moves in response to sound as a travelling wave.

Weta are known to have excellent hearing: they can detect the gentle rustling of a predatory bat creeping through leaf litter. Their ears (which are in their legs!) have an unusual channel that functions like a human’s cochlea, but that uses the lipid, instead of hair cells, to cause vibrations.

We think it’s this unique function that gives the weta their excellent auditory skills.

Weta and the king cricket have their ears to the ground, quite literally, located on each of their front legs.

In a classic example of New Zealand ingenuity being exported across the ditch to Australia, Kate and her team are now attempting to isolate the lipid from the weta’s close cousin, the Australian king cricket, to understand its structure. They can then learn how to synthesise the lipid in the lab, so that they can study its acoustic properties and test its potential acoustic applications.

This is a process known as biomimetics: the mimicking of naturally-occurring systems and elements to solve complex human problems. By unlocking the basic properties of the lipid, Kate and her team hope to replicate its success in, and improve the capability of, auditory technologies like hearing aids, highly sensitive audio sensors, microphones and even ultrasound probes.

Who knows what other surprises the weta may hold for us yet?

Find out more about other bio-inspired materials and devices we’re working on.