This article was first published in The Conversation.

Australia’s future prosperity is at risk unless we take bold action and commit to long-term thinking. This is the key message contained in the Australian National Outlook 2019 (ANO 2019), a report that we published today with our partners.

Our new research used a scenario approach to model different visions of Australia in 2060.

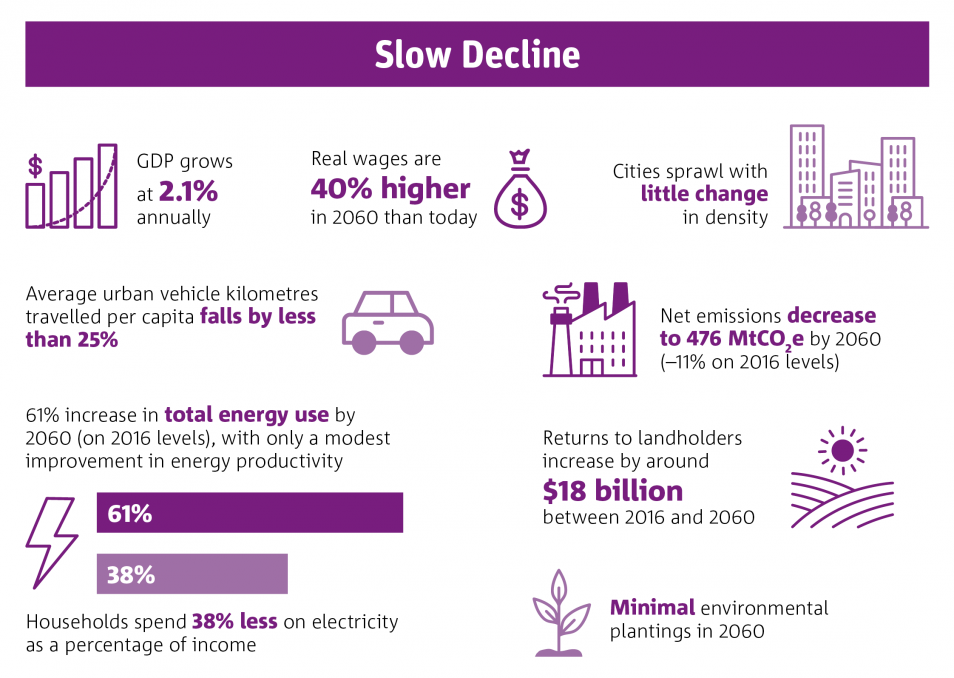

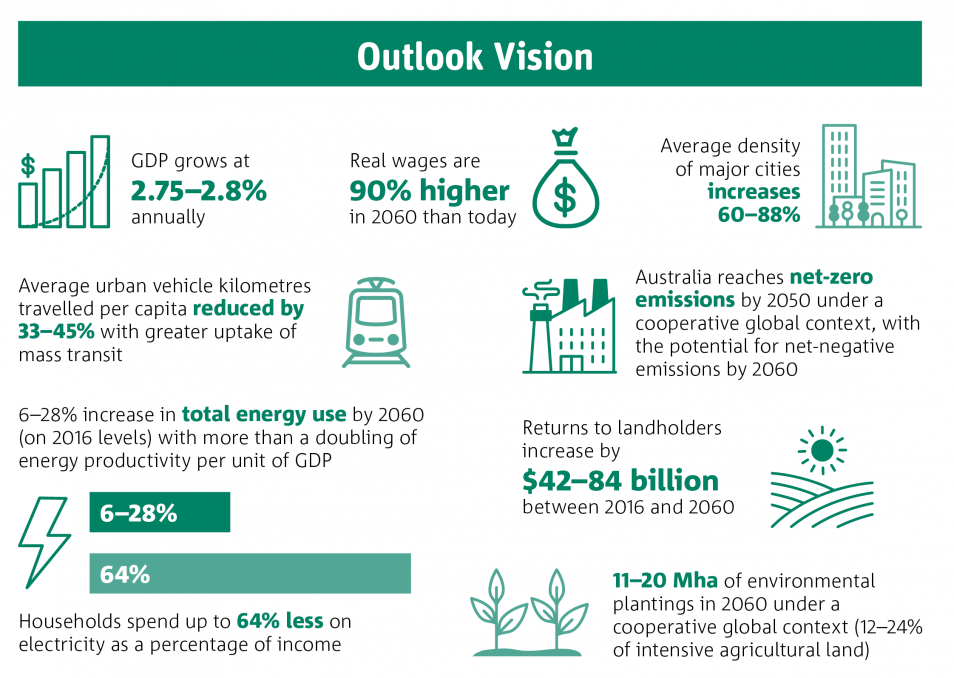

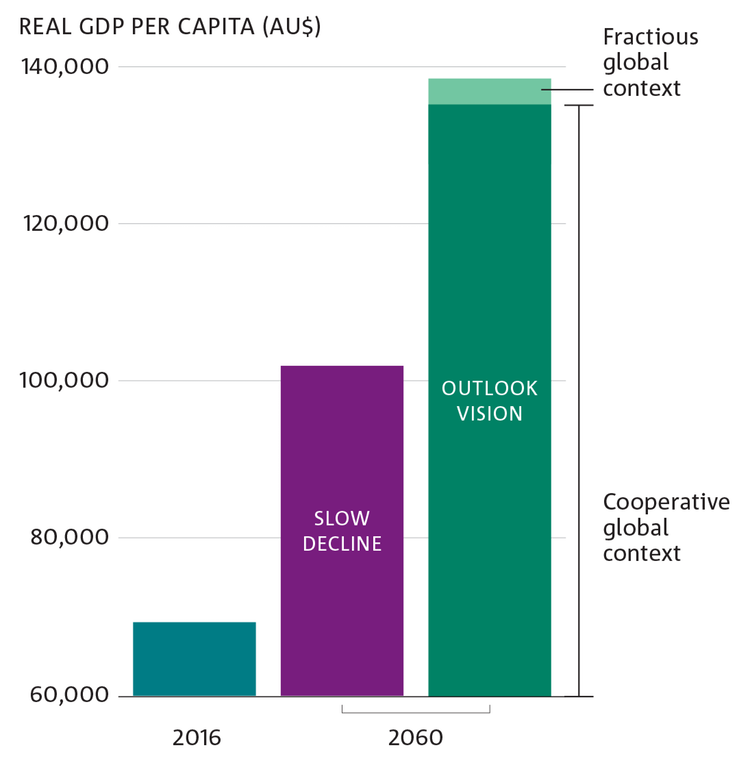

We contrasted two core scenarios: a base case called Slow Decline, and an Outlook Vision scenario which represents what Australia could achieve. These scenarios took account of 13 different national issues, as well as two global contexts relating to trade and action on climate change.

We found there are profound differences in long-term outcomes between these two scenarios.

Slow decline versus a new outlook

Australia’s living standards – as measured by Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita – could be 36% higher in 2060 in the Outlook Vision, compared with Slow Decline. This translates into a 90% increase in average wages (in real terms, adjusted for inflation) from today.

In the Slow Decline scenario, Australia fails to adequately address identified challenges. Image: CSIRO

The Outlook Vision scenario shows what could be possible if Australia meets identified challenges. Image: CSIRO

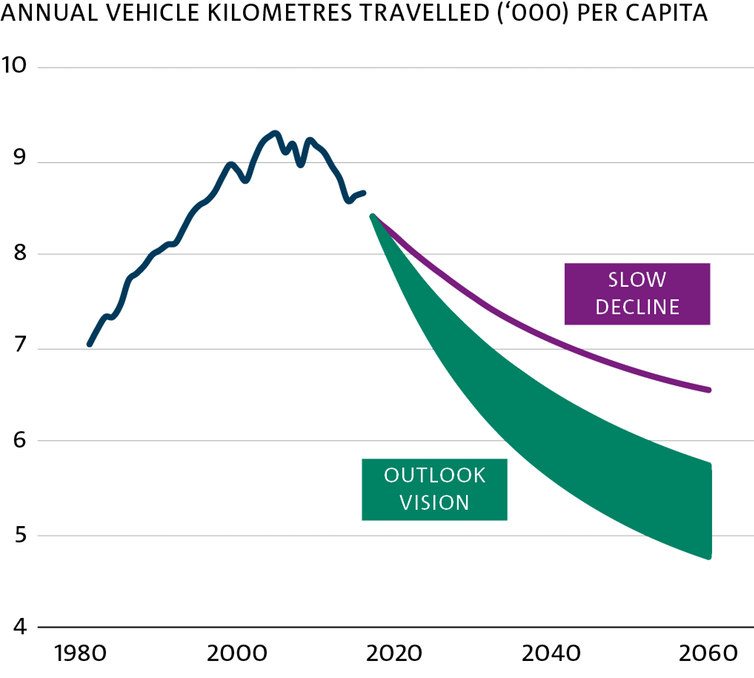

Australia could maintain its world-class, highly liveable cities, while increasing its population to 41 million people by 2060. Urban congestion could be reduced, with per capita passenger vehicle travel 45% lower than today in the Outlook Vision.

Australia’s real GDP per capita in 2016, and the modelled outcomes for Slow Decline and Outlook Vision. In Outlook Vision, the darker shade shows outcomes under a cooperative global context and the lighter shade under a fractious global context. Image: CSIRO

Australia could achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 while reducing household spend on electricity (relative to incomes) by up to 64%. Importantly, our modelling shows this could be achieved without significant impact on economic growth.

Low-emissions, low-cost energy could even become a source of comparative advantage for Australia, opening up new export opportunities.

And inflation-adjusted returns to rural landholders in Australia could triple to 2060, with the land sector contribution to GDP increasing from around 2% today to over 5%.

At the same time, ecosystems could be restored through more biodiverse plantings and land management.

Historical trend for vehicle kms travelled (VKT) on urban roads, per capita, and projections resulting from the modelled Slow Decline and Outlook Vision scenarios. The shaded area for Outlook Vision represents the range of outcomes possible depending on how regional satellites cities develop. Image: CSIRO

The report, developed over the last two years, explores what Australia must do to secure a future with prosperous and globally competitive industries, inclusive and enabling communities, and sustainable natural endowments, all underpinned by strong public and civic institutions.

ANO 2019 uses our integrated modelling framework to project economic, environmental and social outcomes to 2060 across multiple scenarios.

The outlook also features input from more than 50 senior leaders drawn from Australia’s leading companies, universities and not-for-profits.

So how do we get there?

Achieving the outcomes in the Outlook Vision won’t be easy.

Australia will need to address the major challenges it faces, including the rise of Asia, technology disruption, climate change, changing demographics, and declining social cohesion. This will require long-term thinking and bold action across five major “shifts”:

- industry shift

- urban shift

- energy shift

- land shift

- culture shift.

The report outlines the major actions that will underpin each of these shifts.

For example, the industry shift would see Australian firms adopt new technologies (such as automation and artificial intelligence) to boost productivity, which accounts for a little over half of the difference in living standards between the Outlook Vision and Slow Decline.

Developing human capital (through education and training) and investment in high-growth, export-facing industries (such as healthcare and advanced manufacturing) each account for around 20% of the difference between the two scenarios.

The urban shift would see Australia increase the density of its major cities by between 60-88%, while spreading this density across a wider cross-section of the urban landscape (such as multiple centres).

Combining this density with a greater diversity of housing types and land uses will allow more people to live closer to high-quality jobs, education, and services.

Enhancing transport infrastructure to support multi-centric cities, more active transport, and autonomous vehicles will alleviate congestion and enable the “30-minute city”.

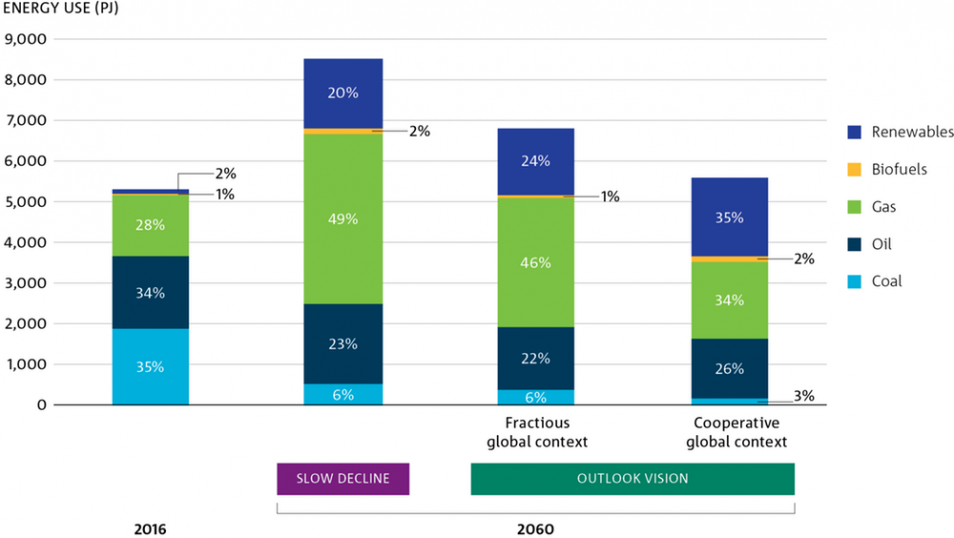

In the energy shift, across every scenario modelled, the electricity sector transitions to nearly 100% renewable generation by 2050, driven by market forces and declining electricity generation and storage costs.

Likewise, electric vehicles are on pace to hit price-parity with petrol ones by the mid-2020s and could account for 80% of passenger vehicles by 2060.

In addition, Australia could triple its energy productivity by 2060, meaning it would use only 6% more energy than today, despite the population growing by over 60% and GDP more than tripling.

Primary energy use in Australia under the modelled scenarios. Primary energy is the measure of energy before it has been converted or transformed, and includes electricity plus combustion of fuels in industry, commercial, residential and transport. Image: CSIRO

The land shift would require boosting agricultural productivity (through a combination of plant genomics and digital agriculture) and changing how we use our land.

By 2060, up to 30 million hectares – or roughly half of Australia’s marginal land within more intensively farmed areas – could be profitably transitioned to carbon plantings, which would increase returns to landholders and offset emissions from other sectors.

As much as 700 millions of tonnes of CO₂ equivalent could be offset in 2060, which would allow Australia to become a net exporter of carbon credits.

A culture shift

The last, and perhaps most important shift, is the cultural shift.

Trust in government and industry has eroded in recent years, and Australia hasn’t escaped this trend. If these institutions, which have served Australia so well in its past, cannot regain the public’s trust, it will be difficult to achieve the long-term actions that underpin the other four shifts.

Unfortunately, there is no silver bullet here.

28th June 2019 at 8:16 pm

It’s good to see someone providing some alternative visions for Australians to consider. I am concerned about the ability of our country’s resources to cater to 41million and would rather see some discussion to stabilise the global population growth. Higher density housing is a definite if we are to save good land for wildlife habitat and farming. I wonder what carbon crops the article refers to but sounds interesting. To me the biggest hurdle is going to be rebuilding trust in governments and politicians.

28th June 2019 at 6:45 pm

Pertinent points Bernie Masters, how about a good old fashioned SWOT analysis, then, and only then, signal the virtues?

28th June 2019 at 5:53 pm

Australia unfortunately today seems to shy away from national visions. Our government’s agenda is cut taxes, hope the RBA will cut taxes and trust everything else will follow. Our alternative government’s agenda was to increase taxes and welfare and spend it on services.

Our culture isn’t much like Asian culture, but I’m struck by how our national debate recently was arguing about franking credits while China has a national plan on how to be global leaders in 12 critical industries by 2025. We are obviously not that large, but we could aspire and co-ordinate strategies to be world class and competitive in several future industries, such as biotechnology, renewable energy, online education, architectural services, smart cities infrastructure and others. However, we need to get over our belief that we have to hang onto sunk costs, like still having 300 years of coal left in the ground. We might as well have said a century ago, “No cars for us, thanks. We still have a lot of horses.”

28th June 2019 at 3:59 pm

Trust in government is getting worse. Members seem incapable of responding to the community with their primary aim to stay in government, never mind the community or the future beyond the next elction. Few seem to understand the risk of climate change with carbon dioxide. There is the potential for enormous negative effect of ignoring the scientifically established cause. In the unlikely event the sientists are wrong we just will have to pay a little more for energy.

We would probably get better representation if we paid less but had more women in both parties.

.

28th June 2019 at 3:46 pm

how will this change if there is a war?

Maybe you could run that through a computer model for us.