Our Argo float robots spent winter under the Totten Glacier. It’s a fast-melting glacier in East Antarctica.

Okay, so our scientists didn’t actually spend their winter in the deep, dark waters under Antarctica’s sea ice. We’re not crazy! It’s really cold down there! But our scientists did develop a new mission for our fleet of autonomous oceanic robots called Argo floats. It may have been a long winter for these brave bots, but the data that they sent back made their mission worthwhile.

What does an ocean robot do?

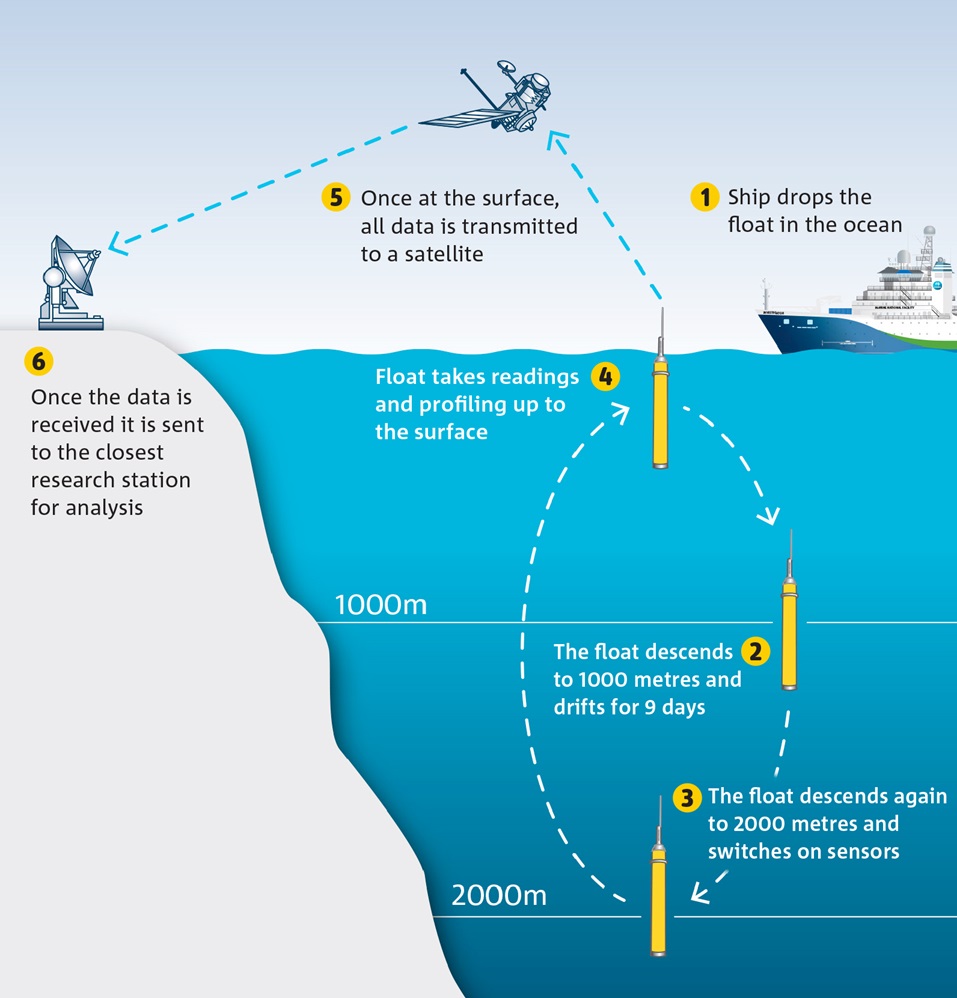

There are currently around 3900 Argo floats bobbing around in the world’s oceans. We manage 360 floats as part of the Integrated Marine Observing System. These specialised instruments move up and down through the water column measuring ocean temperature and salinity as they go. They travel to depths of 1 to 2 kilometres, drifting with the ocean currents. When they surface they use satellite transmission to send their data back to scientists waiting to review results.

(Fun fact: The Argo program is named after the Greek mythical ship, Argo, which Jason and the Argonauts sailed on a mission to retrieve the Golden Fleece. Measurements of sea surface height are called ‘Jason measurements’, complimenting ‘Argo measurements’ of ocean temperature and salinity.)

Up and down and up and down – the Argo robotic float cycle process.

Watch out for the ice

Because Argos need to surface to transmit data, until now, they’ve only been able to collect data about the ocean around Antarctica in summer, when there is no sea ice blocking their path.

But we’re really curious about what’s happening under the sea ice in winter, especially at places like Totten Glacier, a fast-melting glacier in East Antarctica. Collecting measurements in winter, when the ocean surface freezes to form sea ice, has required our scientists to come up with a cunning new approach.

To collect winter measurements near the Totten Glacier they ‘parked’ the floats on the sea floor between water column profiles (so that they didn’t drift away). Then, the team programmed the Argo robots to check for sea ice as they floated up to the surface.

“We programmed the floats to check the water temperature as they were getting close to the surface,” explains Dr Steve Rintoul from our Centre for Southern Hemisphere Oceans Research.

“If the temperature was so low that ice could form, the float would go back down and attempt to resurface after five days, hopefully this time somewhere free of ice. Each water column profile collected under the ice was stored to be transmitted when the float was able to surface.”

Argo floats ready for deployment.

And watch out for the boulders and mud!

However, it wasn’t just sea ice that the Argo floats had to contend with. ‘Parking’ these sensitive instruments on the sea floor also put them in peril.

Steve puts it simply:, “Crashing sensitive oceanographic instruments into the sea floor isn’t generally recommended.”

It’s a confusing life for Argo floats. When they’re on board the ships that send them overboard, Argos are treated with lots of TLC. They have special covers to protect the sensitive instruments from dust, and are transported in soft padding before being every-so-gently lowered into the water.

But once they hit the sea floor, it’s a different story.

“Firstly, hitting the sea floor itself knocks them around a bit, and then there are pretty strong currents down there that cause them to bump along the bottom,” explains Steve.

“In places there are large boulders that they could get washed into, and in other places there’s soft mud, which can be equally damaging as it sticks to and fouls the float’s sensors.”

Dr Steve Rintoul with another kind of Argo float (a biogeochemical Argo float) in front of the RV Investigator.

The Argos answered mysteries from the deep

Our scientists sat nervously through the Argo’s first winter under ice. When spring arrived and the sea ice started to melt, the team waited in anticipation as the golden floats returned to the surface. Would they be ok? Would their sensors be battered and bruised? What secrets would they reveal? Would they successfully transmit their winter data?

Well we are happy to report that the Argos returned unscathed, as bright and buoyant as ever. They were also full of stories (data) to tell (transmit) about their time under the ice.

“We immediately noticed that the ocean was warmer in autumn and winter than we had found in our previous summer measurements,” said Alessandro Silvano from the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS), who led the study.

“The new measurements confirm that this part of East Antarctica is exposed to warmer ocean waters. These warmer waters can drive rapid ice melt, with the potential to make a large contribution to future sea level rise.

“The floats also provided new measurements of ocean depth in the region, revealing a previously unknown deep trough that allows warm water to approach the glacier year-round,” Alessandro said.

Previously, it was thought that most of the glacial melting was happening in West Antarctica, while East Antarctica was thought to be more stable. The data collected by the floats shows that (at least) this part of East Antarctica is also exposed, something that requires further exploration.

“These results show that profiling floats can be used in novel ways to measure the ocean near Antarctica, a critical blind-spot in the global ocean observing system,” said Steve.

“But much work remains to be done and we need more measurements to assess the vulnerability of the ice shelf to changes in the ocean, including in the ocean beneath the floating Totten Glacier.”

Thankfully, we have a trusty fleet of Argo floats who are clearly up to the challenge.

‘Seasonality of warm water intrusions onto the continental shelf near the Totten Glacier’ was published by Alessandro Silvano et al. in JGR Oceans on May 3 2019.

We conducted this research with scientists from University of Tasmania’s Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies supported by the Australian Antarctic Division, ACE CRC, the ARC-funded Antarctic Gateway Partnership and the Centre for Southern Hemisphere Oceans Research.

20th May 2019 at 9:18 pm

When ice forms on high latitude ocean surfaces during winter months (low/zero insolation and contact with cold air allows surface waters to get cold), if deeper layers of water are warm then the ice at the surface retards heat loss to atmosphere – so perhaps it’s not surprising that relatively warm deeper water can persist during high latitude winters.

Does this mean that these high latitude waters can only really dissipate heat to atmosphere (evaporation etc) only during summer months when there’s less (or even no) surface ice?

19th May 2019 at 2:44 pm

Presumably you mean peek under the ice?

20th May 2019 at 8:51 am

Oh! Yes, indeed. Thanks for this pick-up, Peter.

16th May 2019 at 9:21 pm

Remarkable and important