Last year’s record-breaking temperatures are having a devastating impact on the world’s coral reefs. In Western Australia the severity of the situation, which could lead to long-term collapse of reef ecosystems, has gone largely unnoticed.

Last year’s record-breaking temperatures are having a devastating impact on the world’s coral reefs. For only the third time in recorded history, coral reefs are experiencing a global “bleaching” event (where corals turn white; some ultimately die).

Australia’s reefs are feeling the impact, too. The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is in charge of producing global bleaching forecasts. Surprisingly, it isn’t the Great Barrier Reef facing the greatest threat this year, but Western Australia’s less well-known coral reefs.

NOAA predictions for the Western Australia (WA) are about as severe as they get: there is a 60% probability of the most severe bleaching (“Alert 2”) for all of April 2016.

In comparison, the Great Barrier Reef on Australia’s east coast has a 60% probability of milder bleaching (“Alert 1”) for most of March 2016 – obviously still a major concern, but not as severe as for the west.

And bleaching is not the only threat facing Western Austraia’s reefs. While we are well aware of the troubles of the Great Barrier Reef, we must make sure we don’t ignore its less famous western cousins.

El Niño and the western reefs

Recent years have seen devastating marine heatwaves cause massive losses to the underwater kelp forests and corals of Western Australia.

These events typically occur on the west coast during La Niña years (when the ocean is hotter off the west coast), but during the last year the Pacific Ocean has officially returned to El Niño.

This has sparked some hope for the marine environments in WA, because water temperatures are usually cooler in El Niño than La Niña years.

But water temperatures over the past 12 months have been recorded at 1-3°C warmer than long-term summer averages. While this may seem insignificant, global coral mortality previously occurred at these temperatures in 1998 and was observed in all ocean basins in 2015.

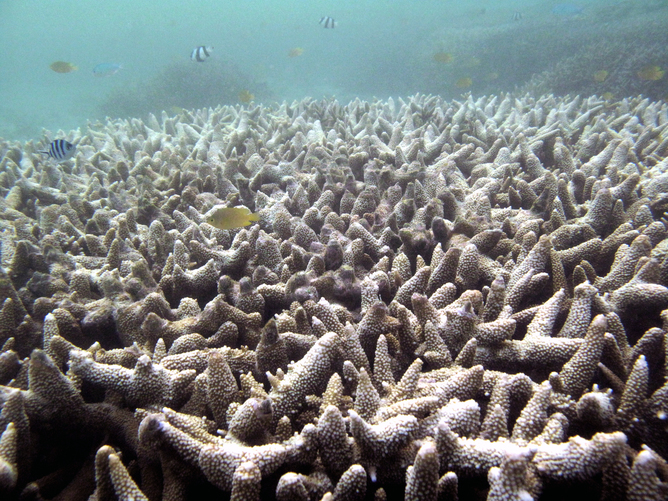

Coral undersea affected by bleaching

Acropora corals during a bleaching event. Image credit – Christopher Doropoulos.

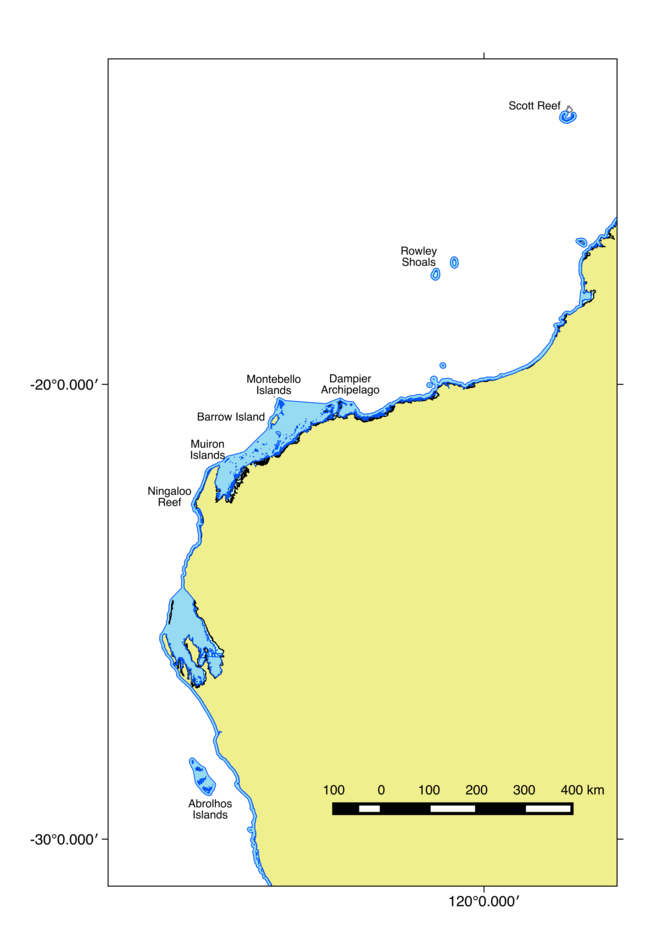

NOAA’s bleaching alert spans most of WA’s coastline. This includes the major coral reef systems of the Abrolhos Islands, reefs in the Pilbara (including Barrow Island, the Montebello Islands, and Onslow) and the Kimberley (including the Rowley Shoals and Scott Reef).

The alert also surprisingly includes the World Heritage-listed Ningaloo Reef. We say “surprisingly” because Ningaloo normally avoids bleaching: it fringes the Western Australian coast and usually receives cooler water welling up from the deep, and from a cool northward flowing current.

That said, Ningaloo experienced massive bleaching in 2011 at Bundegi, on the western side of Exmouth Gulf, where live coral cover crashed from 80% to 6% – almost all the adult coral was killed.

Drawing of map with locations of major coral reefs in Western Australia

Map of major coral reefs in Western Australia. Image credit – Mick Haywood.

Reefs in danger

WA’s coral reefs are unusual because most are isolated from major human populations. They are world renowned for the abundance of unique and iconic fauna they host, a stark contrast to the red deserts they directly neighbour.

Unfortunately, the last few years has seen a series of major environmental disturbances that have compromised the health of these coral reefs.

We recently undertook surveys of reefs from the Dampier Archipelago and Montebello Islands to the Muiron Islands and what struck us most was the depauperate state of the reefs. We saw a mosaic of impacts depending on where we surveyed.

Some places are still recovering from two major rounds of coral bleaching – the event of 2010-11 and another in the Pilbara in 2013. Some were beset by crown-of-thorns outbreaks, and some had high cover of dead branching Acropora (the most abundant coral that builds reefs) that were smothered in sediment, mostly from nearby dredging projects.

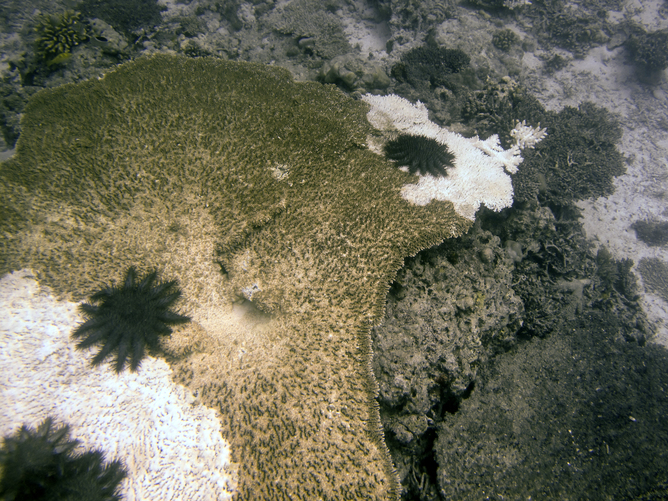

Crown-of-thorns starfish eating remnant Acropora colony.

Crown-of-thorns starfish eating remnant Acropora colony. Image credit – Christopher Doropoulos.

Ironically this region’s isolation is a double-edged sword — the severity of the situation, which could lead to long-term collapse of reef ecosystems, has gone largely unnoticed.

Isolation and the absence of human impacts might help coral reefs recover after coral bleaching. But it also means that few people are familiar with the region’s prolific coral reefs.

Without this understanding, there might not be sufficient public awareness to drive the action required to protect these areas in the face of mounting environmental pressures.

The future for WA’s coral reefs

Coral reefs rely on a range of ecological processes that keep the system resilient and able to function: processes such as the arrival of coral larvae, and removal of algae by herbivores.

However, human or environmental pressures can destabilise or weaken the system, and the ecosystem can swiftly collapse. Once a reef’s ecosystem processes have failed, they are much more difficult to restore than they were to remove, slowing the reef’s return to its optimal state.

Corals are archetypal ecosystem engineers: they provide the foundation for the diversity and abundance of all the other species in coral reef ecosystems. Greenhouse gas increases are contributing to more frequent and intense bleaching events.

Therefore, reefs need every chance to stay resilient by removing local human impacts and being actively restored. After all, without the foundation, there are no coral reefs.

It is time for the coral reefs of Australia’s west coast to be afforded the level of attention and resources devoted to the better known Great Barrier Reef. The system needs time to recover.

![]()

Christopher Doropoulos, OCE Postdoctoral Fellow, CSIRO; Damian Thomson, Experimental Scientist, CSIRO; Mat Vanderklift, Senior research scientist, CSIRO; Mick Haywood, Marine ecologist, CSIRO, and Russ Babcock, Senior Principal Research Scientist, CSIRO

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Pingback: Climate change and coral reefs: have the patterns of coral bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef been replicated on Ningaloo Coral Reef, Western Australia? – James and the Giant Beach

Pingback: 3 Favourite Articles on Climate Change - Caramel & Parsley

29th January 2016 at 5:35 pm

Are these actual bleaching or predicted events in WA?

1st February 2016 at 2:27 pm

Hi,

These events are predicted by NOAA for WA to occur in April 2016. Bleaching has not begun.

-Ellen, CSIRO Social Media Team

2nd February 2016 at 9:49 am

Have such bleaching events ever occurred in WA previously? And where?

I assume NOAA is basing this on predictions of higher ocean temperatures. Where will this arrive from?

2nd February 2016 at 10:12 am

Sorry! I should have re-read the article – about where there were previous bleachings. However, the next 2 questions remain, ie

I assume NOAA is basing this on predictions of higher ocean temperatures. Where will this arrive from?