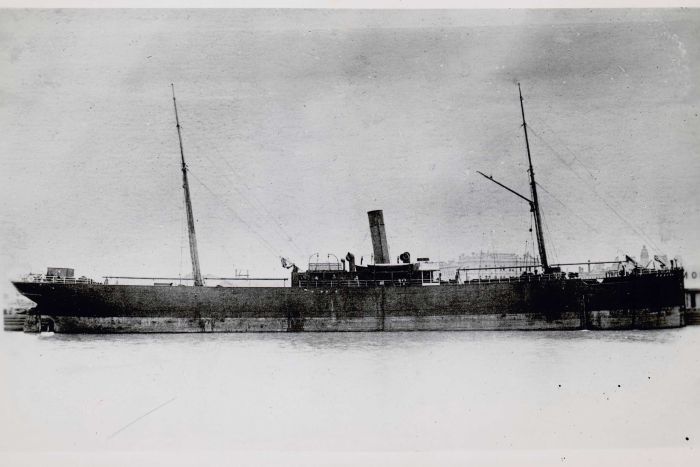

SS Federal was built in 1890 and sank on a voyage from Port Kembla to Albany in 1901. (Supplied: ANMM)

The wreckage of a ship that mysteriously disappeared more than a century ago with no survivors has officially been located and 3D-mapped at the bottom of Bass Strait between Victoria and Tasmania.

Scientists onboard the CSIRO research vessel Investigator surveyed SS Federal seven years after recreational divers filmed the shipwreck and reported it to authorities.

In 1901, SS Federal went missing in a storm as it carried coal from New South Wales to Western Australia with 31 crew onboard.

Australian National Maritime Museum ocean science curator Emily Jateff said the fate of SS Federal largely remained a mystery.

“The interesting thing about it is that we know that the wreck happened on the 21st of March in 1901, but it wasn’t actually reported until the 2nd of April,” she said.

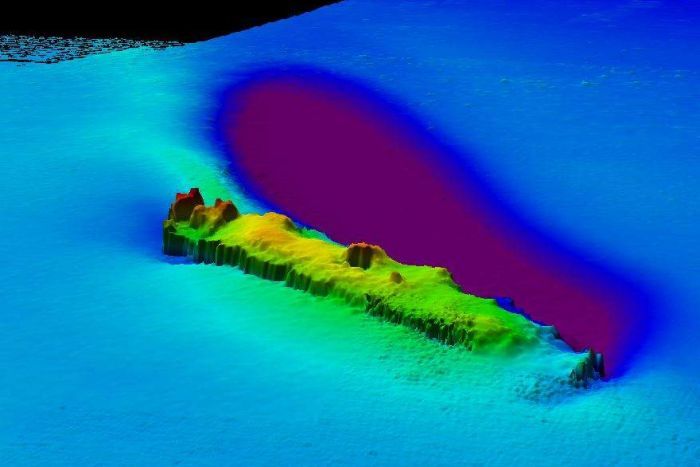

Scientists onboard RV Investigator used multibeam sonar to create a 3D image of SS Federal.

An article in the Mercury on April 8, 1901 reported five bodies had been found on a beach near Cape Everard in Victoria along with a boat “bearing the name of the ill-fated collier”.

According to a document from Heritage Victoria, a Marine Court of Inquiry was held into the loss of the Federal but it was unable to come to any conclusion about what happened to it.

The inquiry found that the crew likely had time to prepare to abandon ship because some of the bodies recovered wore life belts.

“The crew got off the ship but they struggled to get ashore and there were many lives lost,” Ms Jateff said.

“There was an inquiry because they thought more people might have survived if the shipwreck had been reported and crew sent out to see if they could salvage the site or save survivors earlier.”

The researchers used multibeam sonar and a drop camera to map the sea floor and film the wreck.

“It is always important to have the most information that you possibly can about a shipwreck site,” Ms Jateff said.

“It helps in protection, it helps in understanding preservation and it helps in management of the site long-term.”

A sample of Damien Siviero’s footage of the dive on the SS Federal in 2012.

The Victorian Heritage Database stated that during mine sweeping operations in World War I, a sunken object was “fouled in deep water halfway between Ram Head and Cape Everard,” which may have been the ship.

In 2012, recreational diver Damien Siviero explored the wreckage of SS Federal during a diving trip organised by a group of friends.

He thinks the Melbourne-based friends had been tipped off about the location of the shipwreck by local fishermen.

Mr Siviero said he did not know what to expect.

“It was very cold, 10 degrees at the bottom,” he said.

“The water was pretty murky but when you land on a shipwreck, you certainly know it is one.

“When the four or five of us descended, as a pretty tight group, we got to the bottom and you could see the hallmarks of a shipwreck all over the place.”

He said he could only see 10 metres in front of him.

“We all have a limited perspective of what the wreck looks like because you can only see your torch light in any one given distance,” he said.

“So the benefit now of a multi-beam three-dimensional map of the shipwreck as it lies on the bottom is another perspective that can be used to help tell the story.”

Chief scientist Emily Jateff said little was known about what happened to SS Federal.

CSIRO geophysicist Tara Martin said the Investigator’s onboard technology meant they could study the sea floor in high resolution and three dimensions.

“We use sonar to map the sea floor, and that’s basically sending a whole lot of sound beams down to the sea floor and having them bounce back and measure them,” she said.

“If we didn’t have sonar and we were trying to find a shipwreck it would be about as easy as trying to find a needle in a haystack.”

The remains of SS Iron Crown, which was sunk by a Japanese torpedo during World War II, was found during the same Investigator voyage.

‘No point in national park you can’t go into’

There are stringent laws protecting shipwrecks, with wrecks 75 years or older attracting automatic protection under Commonwealth historic shipwreck laws.

There are 15 historic shipwrecks that lie within protected or no-entry zones, which prohibits entry into the zone without a permit.

Ms Jateff said it was important to ensure shipwrecks were as accessible as possible.

“There are certain sites that people probably shouldn’t visit but for the most part,” she said.”We have thousands of shipwrecks across Australia and most of them are public access.

“I think that’s a really important thing to take away, that it is all of our heritage to enjoy and to preserve together.”

The 3D images tell scientists about the condition of SS Federal.

Mr Siviero agreed.

“The question is why do you protect something?” he said.

“I think you should be protecting it so it can be shared and so there’s no point in having a national park that you can’t go into.

“There are very few wrecks that you can’t dive on, but it’d be nice to see some of these open up.”

This article is republished from the ABC. Read the original article.

6th August 2022 at 9:29 pm

My great grandfather was a crew member on the s.s. Federal. His name was George Bibby. He left a wife and two sons, one being my grandfather. It devastated the family.I’m so glad the ship was found.