We're looking at coral reef spawning, one of the largest reproductive events, to better understand coral colonisation and growth.

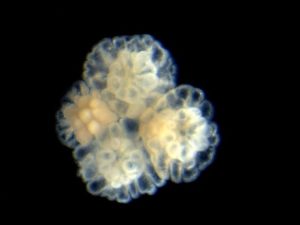

Coral releasing eggs into the water to be met by similarly disseminated sperm. Image: tungkyhandoko/Flickr

Imagine a world without intercourse, a world where men and women cast their sperm and eggs to the wind instead. Though this probably happens regularly on rock tours, for corals, the continuation of their species depends on those gametes meeting in the middle to settle down on a rock shelf somewhere.

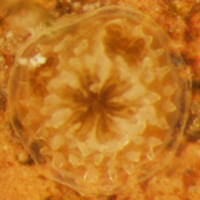

Tiny coral larva, free from the microorganisms that provide them with colour and nutrients.

The only way this reproductive Woodstock can work is if both males and females are coordinated in their ejections — this is difficult to coordinate without synchronised watches or calendars.

So what is the solution for these a-chronic organisms? What consistent, natural calendar can they rely upon to ensure their gametes’ late-night rendezvous occurs at the same?

These animals have found the moon, a regular and dependable sky clock ticking over every 29.5 days.

As the moon rotates its beckoning face around the globe we see, each year, the world’s largest reproductive event as corals let loose their love packages to the currents, an event known as coral spawning.

This year it will occur along Western Australia’s Ningaloo Reef five to ten days after March’s full moon, which fell on the 23rd.

This event is important not just for coral, but for marine scientists studying coral reproduction and colonisation. Our own marine scientists and those from the Western Australian Department of Parks and Wildlife are studying this process: coral spawning, conception, dispersal, and the settlement of coral larvae — the foundations of new reefs and the perpetuation of old ones.

“Coral spawning is a critical process for reef recolonisation. We are also interested in how many new corals survive to adulthood and help rejuvenate disturbed areas,” said Dr Christopher Doropoulos from CSIRO Ocean and Atmosphere.

- 1 week

- 1 month

- 2 month

- Zooxanthellae acquisition

- 1 year

- 2 year

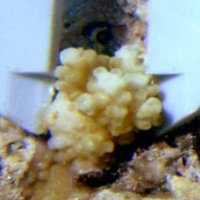

The scientists have been looking at the Ningaloo region which has undergone a bit of a battering from coral bleaching and cyclonic activity. This before and after snapshot of the reef system allows researchers to understand and predict the success of future perturbations to the coral. Especially important are the sensitive young coral colonisers.

“Understanding the early survival of coral recruits involves a series of manipulative laboratory and field experiments”.

The researchers have been introducing artificial terracotta tiles throughout the Ningaloo Marine Park. The terracotta tiles can be manipulated and controlled, and the corals’ colonisation be measured to isolate the factors affecting the tiny animals’ survival.

“We have been working to understand which reefs in WA’s marine parks are most resilient to changing environmental stresses.”

The findings from these types of studies can feed into the planning and upkeep of marine parks and reserves such as the Ningaloo Marine Park.

Ningaloo Reef is a unique natural wonder fringing the West Australian coastline. You can find more information about our marine research here.

16th April 2020 at 1:26 pm

Interesting and well written.

Why do corals spawn at different times on the Great Barrier Reef and at Ningaloo?

22nd April 2020 at 2:41 pm

Hi David, thanks for your comment. Our researchers are currently studying coral spawning to learn more about this process and how it helps our reef. I’d recommend checking out this article from late last year for more information: https://blog.csiro.au/how-multiple-coral-spawning-is-helping/

Thanks,

Georgia

Team CSIRO