New research highlights the importance of using specific shark names to manage conservation.

Here’s a tongue-twister for you, do you know what chondrichthyans [con-drik-thee-ans] are? Well now you do and how to pronounce it. They’re a class of fish containing jawed vertebrates with paired fins. They have a heart with its chambers in series, and a skeleton made of cartilage rather than bone. Its most famous members are sharks.

There are over 500 species of sharks in the world. And more than two hundred of these are found in Australian waters. When we refer to sharks, we usually do so under the umbrella of a collective term. But we might want to reconsider.

All sharks great and small

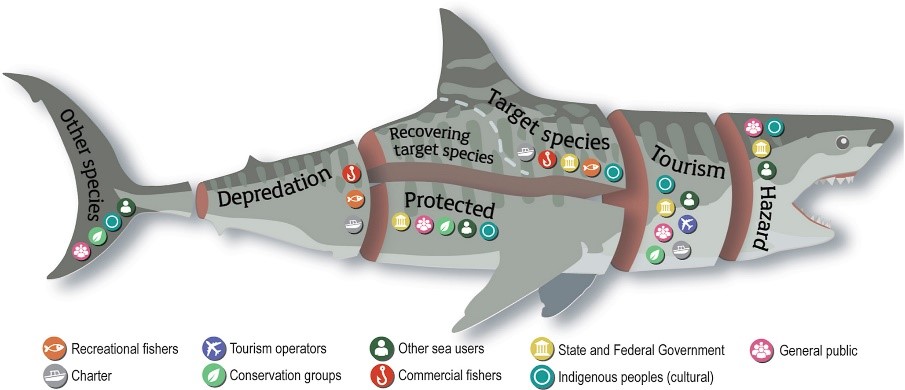

Sharks of all shapes and sizes are an important part of marine ecosystems. Some species are highly valuable for recreational and commercial fishers. Others can be tourism drawcards and important Indigenous cultural symbols. For some beach goers, shark attacks in Australian waters are a fear, even though they are a very rare event. It is a balancing act for decision makers to manage conservation, fisheries, public amenity and safety.

How do we understand the diverse roles of shark species in our oceans, and better manage them? The answer might be in how we refer to the shark.

The need for speed: the mako shark is the fastest shark in the ocean, with a speed of up to 68 kilometres per hour! Image: Patrick Doll

When is a shark not just a shark?

A new article published in Marine Policy suggests people should stop using the umbrella term ‘sharks’. This may help change attitudes to sharks by the media, community, other industries and government.

Scientists at our Australian National Fish Collection in Hobart have described and named many new species of sharks from Australia and the broader region. With such a large number of species, it’s no surprise shark species have a range of lifestyles. Some have relatively short lives and mature early, like whiskery sharks. Others have long lives and may not mature until their late teens or later, just like people. This means longer lived sharks like whale and white sharks, are more vulnerable to the impacts of fishing.

Sharks are also found in a range of different areas, from freshwater to the deep ocean. Some shark populations are restricted to local areas. Others may have ranges that cover entire ocean basins.

With more than 200 shark species in Australian waters, management strategies need to factor in conservation, industry, sustainability, tourism, Indigenous values and public safety. Graphic: Jen Middleton

To know them is to love them

Our research shows there are two distinct white shark populations – eastern and south-western. Each population rarely crosses Bass Strait. Defining a species by area such as ‘eastern Australia white sharks’ may support and inform discussions. It may help engage the media and Australian community to better understand specific issues and management strategies.

Other species also hang out in different waters around Australia. Gummy sharks swim across the shallow waters from WA to NSW. Dusky whalers often swim along our east, west and southern coasts. Mako sharks, capable of travelling up to 68 kilometres per hour, are widely dispersed across all Australian states.

Grey nurse sharks also have two distinct populations. The east coast population primarily lives along the eastern seaboard. It’s classified as critically endangered. The west coast population lives along the coastlines of Western Australia and is classified as sustainable. Tiger sharks have excellent sense of smell and sight.

Using the right shark names might help change community attitudes about the animals. Image: Galeocerdo Cuvier

Precision is the key to future research

Being precise about the species of shark, where they live and the issues at hand may increase effective communication. An understanding of a shark’s conservation status and values will better inform policies for ongoing management.

Advances in genetics such as environmental DNA or (eDNA) allow species identification in an area based on traces of DNA in the water. And close-kin mark-recapture uses a shark’s DNA to generate population estimates. These are already assisting with species and population identification. It gives us intel on how many there are and trends. And these techniques can help provide this information sometimes without needing to see or capture a shark.

Further application for a range of shark species will help balance diverse socio-ecological needs, including conservation and public safety. And, help to get the names right.