Part of the Biosecurity Series

By guest blogger Professor Peter Doherty

Image: caribb/Flickr

It’s no big secret that we’re citizens of an increasingly globalized planet where ideas, information, goods and services get around very fast. One of the downsides of this brave new world is that the same is true for pests and pathogens.

The security services, customs officers and quarantine regulations/officials protect Australia from such invasions as much as possible, although given the volume of trade and human movement, stopping bad things at the borders can only be part of any effective strategy.

There’s also a need for continual environmental monitoring to make sure that nothing dangerous slips through which could compromise Australia’s agricultural industries, wildlife and natural environments.

When it comes to biodefence against invading viruses, bacteria, insects, plants, marine parasites (on the hulls of ships) and so forth, we have layers of operation that function both at the Federal and State level.

This is, of course, where the wonderful high security CSIRO Australian Animal Health Laboratory (AAHL) comes into its own, providing the essential diagnostic tools and facilities for safe studies of deadly viruses in animals that are unique to the South-east Asian region.

The Australian Animal Health Laboratory in Geelong, Victoria

Apart from its service to the veterinary world, AAHL has also pioneered studies of bat-borne viruses like Hendra and Nipah (active to the North-West of Australia) that can transmit to people from infected horses and pigs respectively. These are classic cases of the “One Health” view CSIRO takes that stresses the intimate interplay between animal disease and human disease. Apart from the Henipaviruses, AAHL also has the facilities that allow CSIRO researchers to study the avian influenza A viruses, that are a looming threat to both domestic poultry and people.

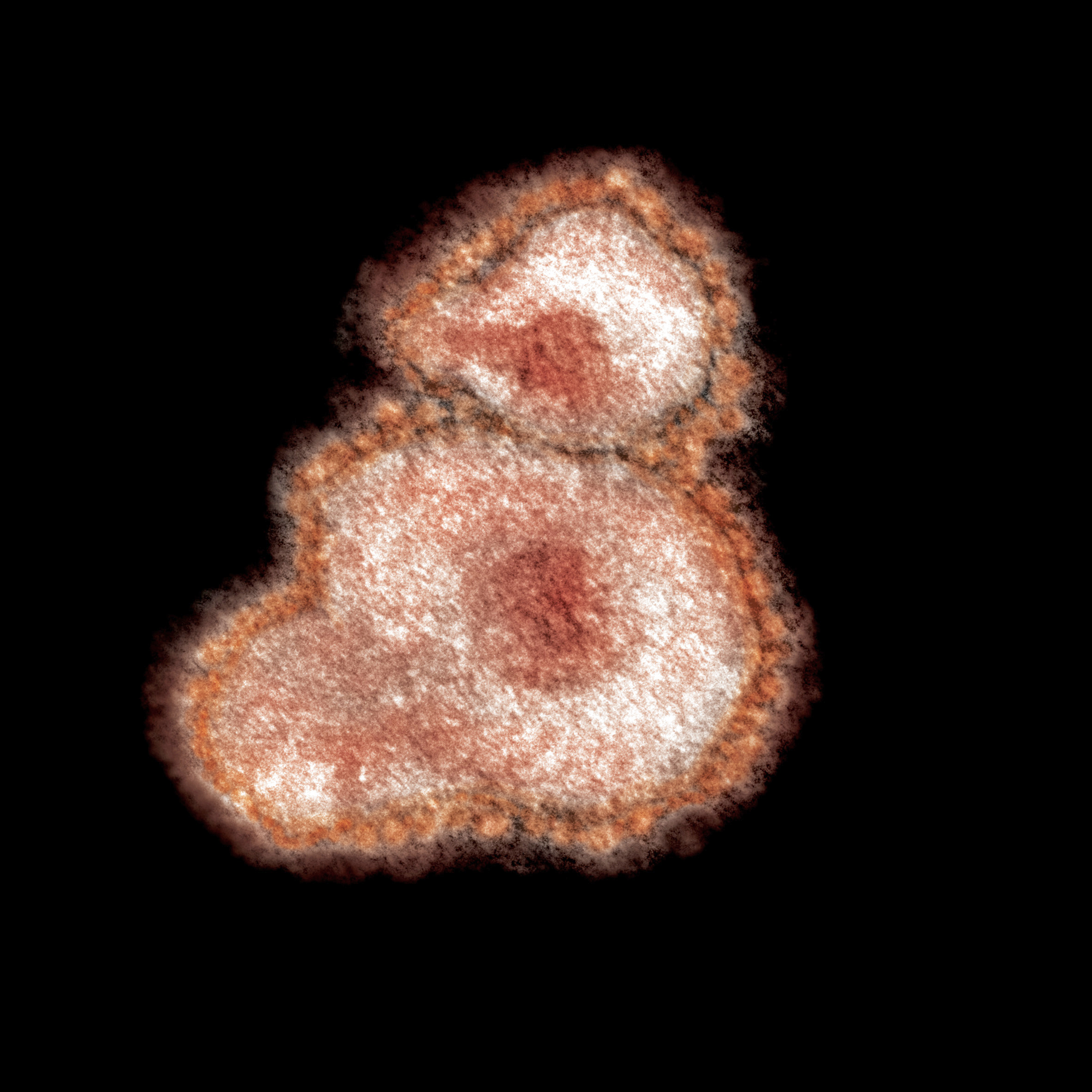

An artificially coloured electron micrograph of the new-SARS like virus – now known as the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) – which has caused an ongoing outbreak of respiratory disease and has spread from the Middle East to the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Italy and Tunisia. (click for full size image)

The new CSIRO Biosecurity Flagship pulls together research capability from across CSIRO together with a broad range of collaborating centres and groups. Sharing information is vital for such activities. Clearly, Australia cannot afford to have “silos” and artificial barriers that in any sense compromise our biological security. Of ongoing concern are the hi-path variants of the avian influenza H5N1 viruses that continue to circulate in wild and domestic birds (and occasionally infect and kill people) in the countries to the north-west of Australia. While we’ve avoided that particular threat so far, the situation requires constant monitoring.

Another threat is the recently emerged H7N9 avian influenza virus and MERS, a novel coronavirus in the Middle East.

I’ve said nothing about plant, insect and fish pathogens, but there are many diseases of key species, such as bees, trout and salmon that we have so far managed to keep at bay.

The new CSIRO Biosecurity Flagship is a great step in the right direction, and we need to continue doing all that we possibly can to ensure the long-term health and wellbeing of all the life forms that inhabit our extraordinary and unique country.

Join the Conversation: #bflaunch

About the Author

Peter Doherty trained initially as a veterinarian and shared the 1996 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for discoveries concerning our immune defence against viruses. He published the non-fiction book “Sentinel Chickens: What Birds Tell Us About our Health and our World” in 2012, and his new book “Pandemics: What Everyone Needs to Know” will be available in Australia from October.

Follow Peter on twitter: @ProfPCDoherty