From Wes Anderson to Jules Verne and the masterpiece that was Waterworld, for decades, the fictional idea of a floating science lab or research ark has captivated our imaginations.

The fourth and final winner of our World Oceans Day Competition got us wondering about fact versus fiction. Here’s what Rita de Heer suggested.

“Convert large superfluous still-seaworthy freighters into floating island arks to accompany gyre clean-up efforts, using onboard sustainable power plants to fuel living and research quarters, labs, pools and ponds for rehabilitation of sea-creatures to arrest the ongoing losses to plastics.”

Convert large sea freighters? Rita had a winning idea. Illustration by Campbell Whyte.

So, what’s the viability of a floating lab? We asked our scientists for their thoughts.

Floating lab a big tick for ecosystem rehabilitation

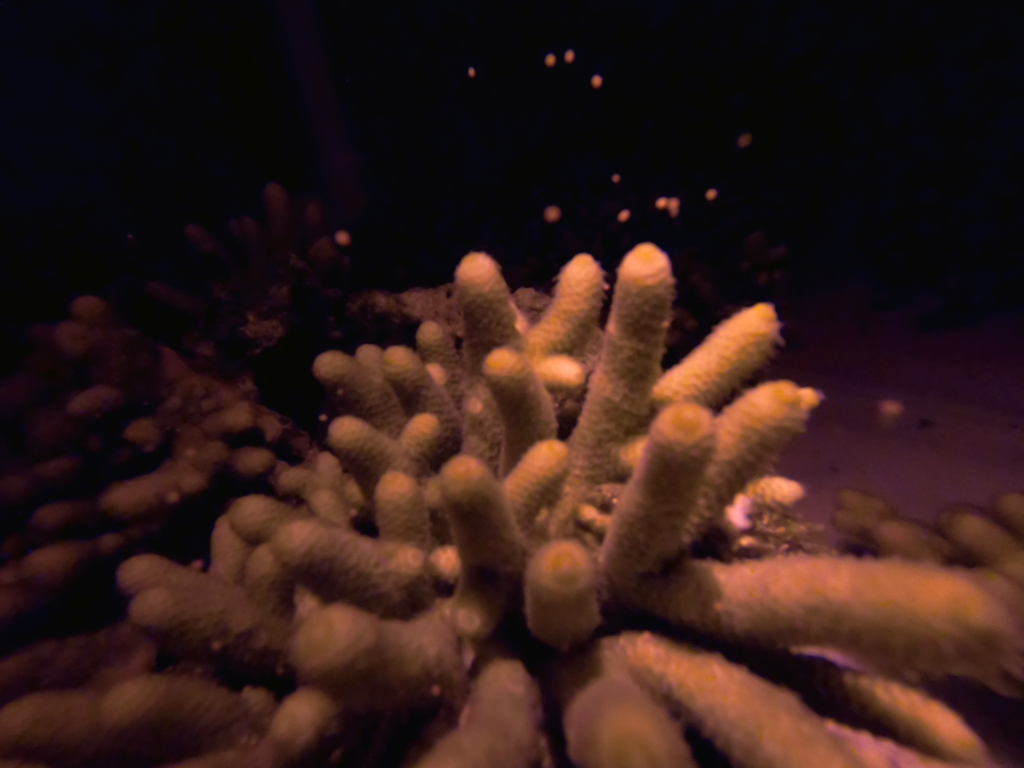

Each year, our coral reef researcher Christopher Doropoulos heads to the Great Barrier Reef to witness and learn from annual coral spawning events.

When it comes to studying coral, it’s one of those ‘you had to be there’ moments. Some coral species spawn like clockwork. On a set number of days after the full moon and hours after sunset – but there are always exceptions.

“It’s a bit nerve wracking, because there’s so much anticipation leading up to it. We have a general idea of when it’s going to happen but not the exact moment,” Chris said.

“So every day we prepare in case the spawning event occurs. The initial set-up requires continual maintenance. Our research activities can go on for 48 or 72 hours, often running on limited sleep.”

Being able to travel on an equipped research ark to observe and harness coral spawning events around the world would come in handy. Coral researchers need to take samples during the spawning event, so a research ark would allow them to access the events and then mimic the natural environment on board.

Chris’ fieldwork is critical to understanding the lifecycle of coral. It provides essential knowledge for future rehabilitation efforts. Researchers usually rely on aerial surveys to capture the span of coral bleaching events. Then water surveys are used to diagnose the mortality of the corals on the reef. Surveys conducted on the ark could include diving or technology deployed off the research ship. For example towed cameras, or autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) or remotely operated vehicles (ROVs).

We could put more research stations where they are needed, bolstering future rehabilitation with improved data collection. This could help researchers target known areas for rare and endangered species. There are over 600 different types of coral in the Great Barrier Reef alone!

“Corals can recover from bleaching. But it depends on the severity of the event on whether those corals will die or recover,” Chris said.

Coral spawning is one of those ‘you had to be there’ moments. Itusually only happens once a year after a full moon. Image: Christopher Doropoulos.

And for tackling plastic waste

Dr Qamar Schuyler is a research scientist in our marine debris team. She looks at the impact of marine debris on creatures like sea turtles.

“There are a lot of things that appealed to me about this idea. Especially reusing something that already exists, like a vessel,” Qamar said.

“One of the challenges of studying ocean plastics is that we have a mammoth area of ocean and we can only hit a targeted number of spots.”

Much of Qamar’s current research is on land and nearshore areas. In 2018, her team shed light on the impact of plastic on sea turtles found in coastal areas.

“We found that it is a numbers game. 14 ingested pieces of plastic causes a relatively high rate of mortality for coastal turtles but we have far fewer data on the turtles in the open ocean.”

“Not all plastics are created equal. Some are quite harmful and some are not. Out in the open ocean, there are different types of plastic, and they tend to be smaller. It would not be out of the question to think that a turtle out there could eat far more plastics before having a 50 per cent mortality risk.”

A platform at sea would also allow specialists to come across animals that might have a chance at rehabilitation. Before they have washed up on shore.

As for Rita’s suggestion on ocean clean ups, there are lots of challenges. Even at the densest points in oceanic gyres, Qamar describes it as “only specks of plastic in the big soup of an ocean. It’s not as simple as putting a net in and scooping it up.”

“Do we have the knowledge and technology to create a plastic–free ocean? I think we do, but achieving that will take a global effort,” Qamar said.

“Ultimately, we want to stop plastics entering the ocean in the first instance. Our research is looking at the whole of the pipeline. Starting at the top by changing how we manufacture materials. Then working down the chain to avoid single use plastics. By the time plastic reaches the ocean, we’re about as far down the pipeline as you can get. In that sense, cleaning up is the least useful point.”

Investigator was purpose-built for a wide-range of research. The ship before it was the Southern Surveyor which was a converted fisheries trawler that was refitted for research.

Wait – don’t we already have a floating lab?

We have our own research vessel, Investigator, which can spend up to 300 days at sea per year!

Marine geophysicist Tara Martin was part of the team who commissioned the scientific equipment on board Investigator. Tara said the ship can support some live animals on board and has a raft of sustainability measures in place.

“We have incubation tanks on the deck, which we sometimes fill with seawater to grow and transport sea creatures we’re studying such as krill,” Tara said.

“The vessel is capable of making its own fresh water from the sea water around it. We have a strict recycling program on board too.”

Before Investigator, we had Southern Surveyor which was originally a trawler converted into a research vessel. But we’ll explain why it might not be what Rita had in mind.

“We know large vessels require lots of people and power to run. Ships use a lot of energy to get to where they’re going and to ‘keep the lights on,’” Tara said.

“Gyres are marine creature hotspots, but they also move, so it would need to travel to keep up with one. The ocean is also a harsh environment for metal.”

And in terms of renewable energy on research vessels like solar power, it isn’t out of the question. But there’s some considerations around the technology being ready.

“So far, only smaller vessels, like AUVs (autonomous underwater vehicles) operate on renewables like wave or solar power,” Tara said.

Tara agrees it would be fantastic to find a job for the many old freighters which roam our oceans. But it might be more viable to consider some small-scale autonomous solutions for our future oceans instead.

Congratulations again Rita for your thought-provoking idea for a floating lab!

18th June 2020 at 2:07 pm

Tara is correct in saying that AUVs can operate almost infinitely on renewable energy such as wave and solar power; the principle is scaleable and if a big, empty ship is available it wouldn’t be too hard to convert it to run its ‘hotel’ services on renewables while retaining a big diesel for propulsion. Eventually, even propulsion could be via renewable energy. The trick would be finding a suitable ship with big tanks for seawater, plenty of deck space for solar panels and/or wind turbines and internal space for laboratories and workshops. It would also need accommodation for a skeleton crew as well as embarked scientists. The cost of acquiring and converting such a ship wouldn’t be negligible, however: a governmental sponsor, or multi-national scientific grant or even a commercial sponsor would be necessary. But it’s worth pursuing the idea.