In a collaboration with the Synchrotron, we used our powerful Maia analysis system to reveal the hidden painting beneath Degas' Portrait of a Woman.

Portrait of a Woman by Degas

The National Gallery of Victoria’s exhibition Degas: a new vision has provided just that, courtesy of a collaboration between us and the Australian Synchrotron.

While 206 artworks are on display, a 207th — hidden under an existing portrait — has just been brought into stark relief, and our powerful “Maia” detection and analysis system played an important role.

During the 1860–1870s French Impressionist Edgar Degas began work on a portrait, then set it aside and later painted another work over the top. Known as “Portrait of a Woman” (Portrait de Femme), it was painted by Degas using thin layers of pigment. As they aged and faded, parts of the earlier work emerged from underneath – but never quite enough to identify the earlier subject.

That was until now. As the painting sat in a custom made cradle, a precise beam of high energy x-rays from the Synchrotron was used to penetrate the layers of paint and make them emit a small amount of light. Our Maia system detected and analysed this microscopically faint glow to catalogue the brushstrokes and pigments used in “Portrait of a Woman”.

Maia created a massive, 31.6 million pixel image that details what chemical elements each pixel possesses. While the pixel by pixel scan took 33 hours, actually analysing the data from it was instantaneous, thanks to Maia’s powerful, purpose built hardware.

The result? A paper just published in “Scientific Reports” has suggested the identity of the painted over figure as one of Degas’ favourite models, Emma Dobigny (real name Marie Emma Thuilleux).

Portrait of a Woman.

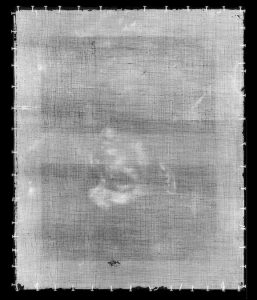

Portrait of a Woman under X-ray — note the upside-down underpainting.

Rendering of the ‘hidden’ Portrait of a Woman.

Our Robin Kirkham said “NGV, Australian Synchrotron and CSIRO couldn’t have made this identification with conventional techniques. It was thought the hidden figure was indecipherable.”

“These processes are revolutionising how art is authenticated, studied and preserved. Knowing an artworks’ chemical composition is the first step to working out how it may deteriorate and develop a plan to minimise that.”

Paper co-author Saul Thurrowgood created special software that turned Maia’s reams of data into a colour rendering of a portrait not seen in at least 136 years.

It’s not the first time we, the NGV, and Synchrotron have joined forces to solve an art mystery. In 2010 similar techniques were used to find a hidden Arthur Streeton self-portrait buried under layers of lead paint and in 2015 a major project helped uncover the hidden secrets in Frederick McCubbin’s The North wind.

Working with with its partners in the United States’ Brookhaven National Laboratory, we have exported Maia technology around the world. When it’s not focussed on famous artworks Maia is used to analyse mineral samples and help in other biological, geological, medical and material testing.

Degas: a new vision is exhibiting at the National Gallery of Victoria until 18 September.