A CSIRO scientist who had his home broken into has developed a new crime scene identification technique to help collar criminals.

Attention to all aspiring robbers, cat burglars, and home invaders: don’t ever break into a scientist’s house. You’re only going to make life harder for yourself in the long run.

Case in point? One of our materials scientists, Dr Kang Liang, had his house in Melbourne broken into recently. Like the rest of us he went through the usual emotions: anger at the invasion of his privacy and property, fear of what could have happened, and thanks that things hadn’t been worse.

But whilst watching the police dust his house for prints, his inquisitive mind kicked in.

“When my house was broken into I saw how common practice fingerprinting is for police” said Kang.

“Knowing that dusting has been around for a long time, I was inspired to see how new innovative materials could be applied to create even better results.”

Kang works with very useful metal organic framework (MOF) crystals. These little gems are extremely porous and can be designed to bind or grow around biological or organic material.

MOFs are already being used in an incredibly wide range of applications, but Kang was struck by the potential for MOF crystals to be used in forensics to help investigators gather evidence.

He and his team then set to work, by experimenting with a range of handled household items including a knife, scissors, plastic light switches and a wine glass; applying the crystals to see if they would grow around fingerprint residue.

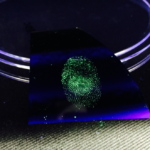

So how does it work? The tiny MOF crystals rapidly bind to fingerprint residue, including proteins, peptides, fatty acids and salts, creating an ultrathin coating that’s an exact replica of the pattern.

“Because it works at a molecular level it’s very precise and lowers the risk of damaging the print,” says Kang.

The method works on any nonporous surfaces including glass, metal and plastic.

“While police and forensics experts use a range of different techniques, sometimes in complex cases evidence needs to be sent off to a lab where heat and vacuum treatment is applied,” Dr Liang said, “our method reduces these steps, and because it’s done on the spot, a digital device could be used at the scene to capture images of the glowing prints to run through the database in real time.

“As far as we know, it’s the first time that MOF crystals have been researched for forensics.”

MOF crystals have a number of benefits in that they are cheap, react quickly and can emit a bright light. The technique doesn’t create any dust or fumes, reducing waste and risk of inhalation.

This new method could save valuable time and costs for police, and help in future investigations.

Want to learn more about the wonderful world of MOFs? You can find out more about these next generation smart materials on our website.

21st October 2016 at 10:49 am

Fantastic lets hope those managing the relative police process has a really long hard look at this.

12th December 2015 at 11:18 am

Wonderful CSIRO is finally talking itself up,long overdue for the wonderful work done and being done, as for taking science to the schools Terrific.

5th November 2015 at 5:23 pm

awesome Dr Kang Liang and CSIRO