We’re field testing a new malaria breath test to help the global fight against malaria, which killed more than half a million people in 2013 alone.

Close up view of the malaria-carrying mosquito, Culex pipiens.

It goes without saying that breathing is pretty darn important. Aside from the obvious benefits of filling our lungs with oxygen every couple of seconds, your breath can say a lot about you.

We’ll not get into the garlicy kebab after a night out kind of breath, but food, drink and even disease can be detected in a single breath.

Breath tests have been around for a while. It is about 34 years since random breath testing for alcohol was introduced in New South Wales. Recently, a study in the Journal of Breath even showed that conditions including Type 1 Diabetes, colorectal cancer and lung cancer could potentially be detected by breath testing.

Last year we made a breath-related discovery of our own. We found that by identifying distinctive chemicals (markers) in breath, we may be able to detect whether someone is infected with malaria. According to the World Health Organisation, almost 200 million people caught malaria and more than half a million of them died from it in 2013 alone. Currently, diagnosing malaria involves using powerful microscopes to look for parasites in blood using a method discovered in 1880.

Malaria.

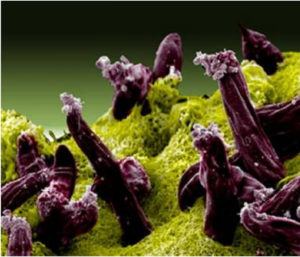

Scanning electron micrograph of Plasmodium gallinaceum (plasmodium that causes malaria in poultry) invading mosquito midgut. Credit: NIAID

Thanks to a $1.4 million research grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation we announced today, this could change. Our research team will be working with partners to field test the breath markers in Malawi, Bangladesh, Sabah province in Malaysia and Sudan.

This next stage of our research is a collaborative effort with the QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, Menzies School of Health Research and Washington University in St. Louis, USA. In the field trials, people with suspected malaria will be asked to provide a breath sample in addition to the testing and treatment that they receive at health clinics. Other patients, who are not suspected to have malaria will act as controls and also have their breath samples taken.

There’s no doubt breath testing has come a long way, but not even CSIRO will be able to develop a test to measure that smelly souva.

We’ve worked on developing a range of similar bioproducts – you can read more about them here.

For media enquiries, contact Andreas Kahl on andreas.kahl(at)csiro.au or +61 407 751 330.