A new strain of avian influenza emerged in China recently, where it ‘spilled over’ into the human population, causing 37 deaths.

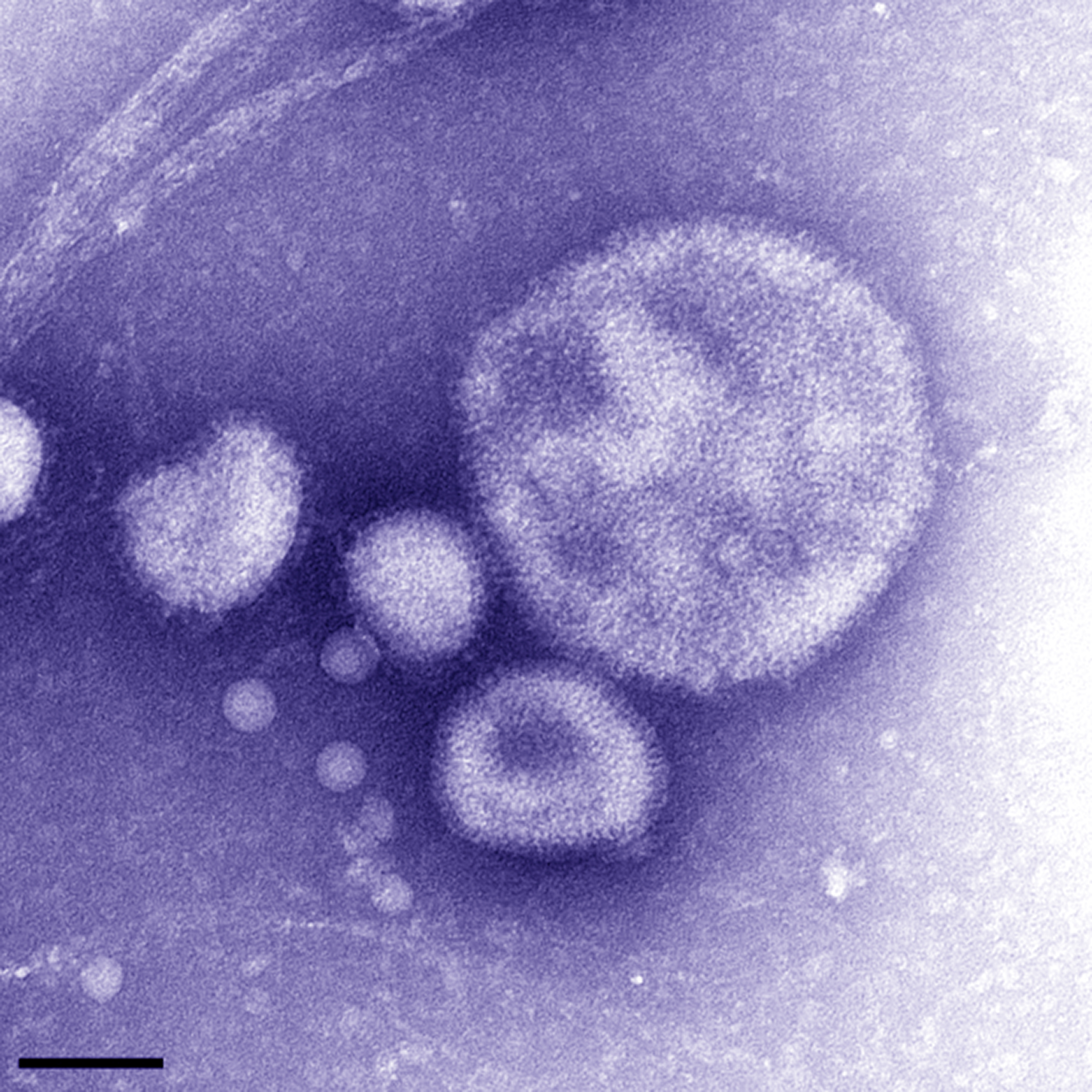

Mug shot of a one of the world’s new deadly viruses, A(H7N9).The four blobs in this electron micrograph are the virus.

The virus, A(H7N9), has a mortality rate more than twice as high as SARS, with over 25 per cent of the 131 infected people dying.

So what does this mean for Australia? So far, all the cases have been in China, but with thousands of people travelling the globe every day, there is a possibility that the virus could quickly jump between countries. One of the victims was a Taiwanese man who recently returned from China.

The source of the virus has proved difficult to track, as it’s considered ‘low pathogenic’ in poultry, which means that even though it’s deadly to humans, infected birds don’t get sick.

So far the suspected method of transmission is thought to be direct contact with live infected poultry, most likely at live bird markets. While these markets are uncommon in Australia, we would face a very different situation if the virus evolved into a form that was more contagious to humans, and was able to spread through direct human to human contact.

The scientific response

Chinese authorities announced the new virus on 31 March, and very quickly made samples of the virus available for international collaborators to form a global response.

Our Australian Animal Health Laboratory (AAHL) is an international reference laboratory for animal influenzas, and was one of the biosecure labs around the world to receive the live virus for testing.

In the high biosecure facilities at AAHL, our scientists collaborated with colleagues around the world on behalf of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation, to fine tune and validate a test to detect H7N9 in Asian poultry, over a backdrop of other viruses prevalent in the region.

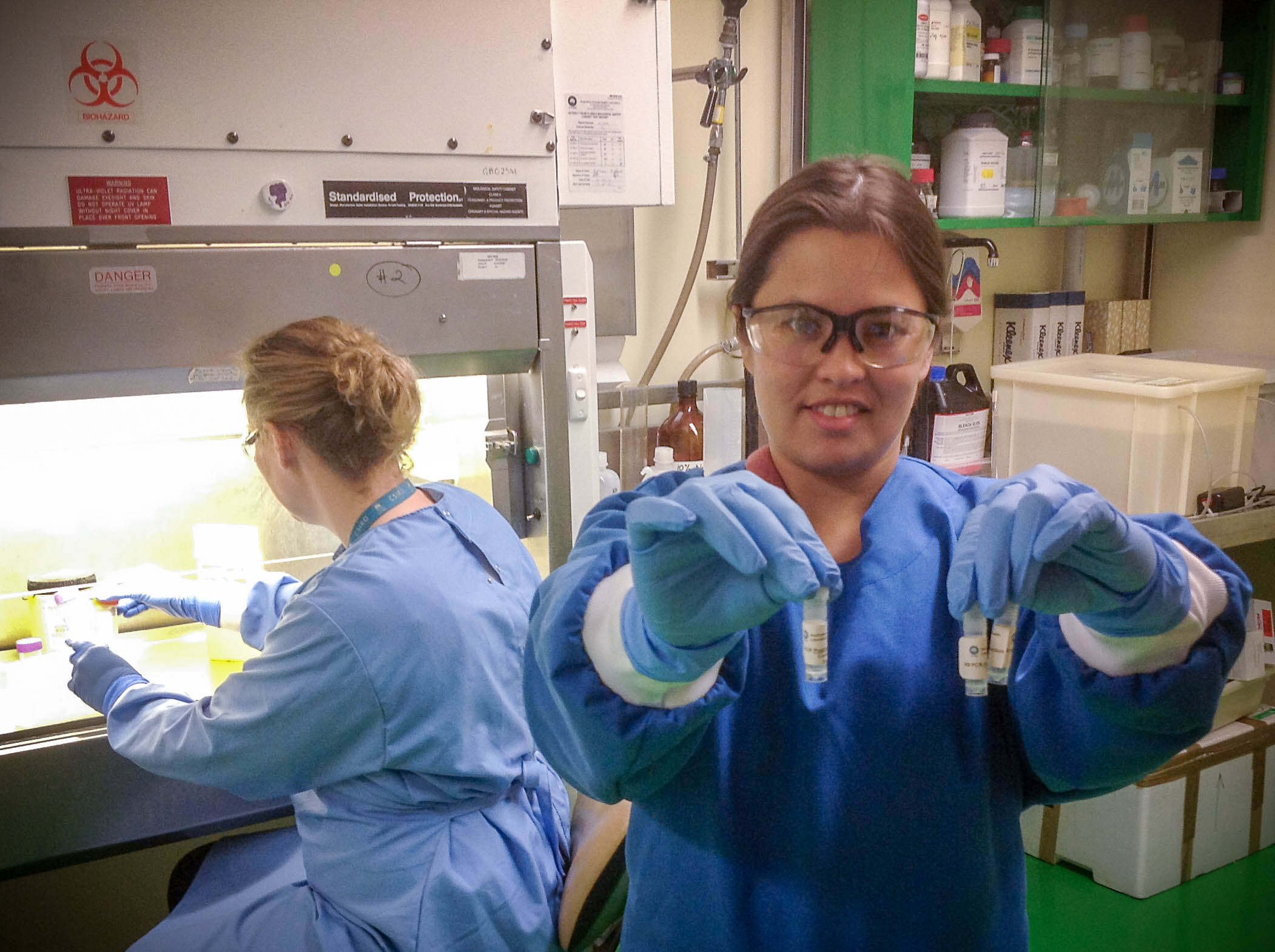

AAHL scientist Mai Hlaing Loh with a test kit bound for Asia.

We’ve made the test available in kit form so that qualified labs in Southeast Asia can test for the virus in their own poultry populations. We started distributing the kits in May, and the next delivery is destined for Bhutan and Nepal later this week.

The kits themselves look unremarkable – about half the size of a tissue box, yet they contain enough reagent for around 16,000 tests. With the H component and N component of the virus needing to be tested separately, each kit can test almost 8 000 birds. The test is a real-time PCR genetic analyses, and results are available within a few hours.

As well as helping our nearest neighbours, surveillance of H7N9 in poultry populations strengthens Australia’s pre-border biosecurity by helping us prepare for the movement and possible evolution of the virus, and to better manage the public health threat.

There haven’t been any reported cases of human to human transmission yet, but being prepared for a quick response will be key for saving lives in the face of any potential outbreak.

Media: Pamela Tyers. Phone: +61 3 9731 3484. Email: pamela.tyers@csiro.au