The 2019–20 Australian bushfires occurred during a period of record-breaking temperatures and extremely low rainfall.

More than 18 million hectares of land burned. Images of the catastrophic impact the fires had on communities in Australia’s south and east dominated news headlines for weeks. But the impact of the bushfires was also felt further afield – in the ocean.

From December 2019 to March 2020, researchers found something interesting in the previously desolate regions of the Southern Ocean.

They discovered widespread blooms of phytoplankton – photosynthetic algae – that are the powerhouses of ocean ecosystems. A phenomenon likened to turning the whole Sahara Desert into grassland for four months.

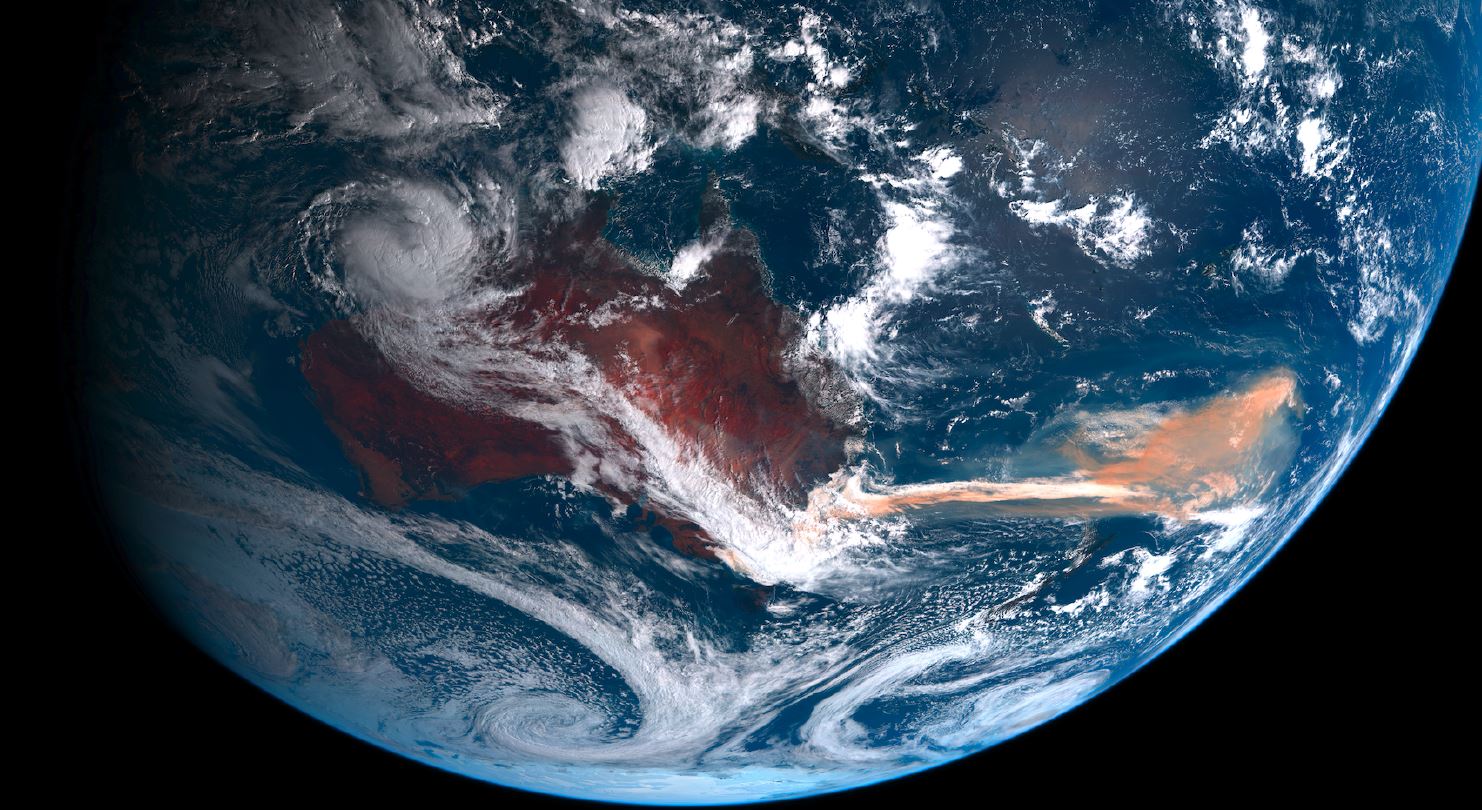

The Australian bushfires caused an enormous ash and smoke plume. The orange smear off the east coast of Australia represents this plume. It carried iron-rich aerosols through the atmosphere to the Southern Ocean.

Iron-rich plumes

Almost all living organisms require iron as a critical trace element. Therefore, iron plays a key role in metabolic processes such as DNA synthesis, respiration, and photosynthesis.

The Australian bushfires emitted around 830 million tonnes of CO2. Within the large clouds of ash and smoke blown away from the continent were iron-rich aerosols from the land.

The Southern Ocean is nutrient rich but typically has low levels of iron. The availability of iron places a limit on how productive these areas of ocean can be.

Following the bushfires, iron-rich aerosols were transported through the atmosphere and deposited into the ocean. Satellite imagery showed phytoplankton blooms flared in these iron-fertilised regions of the Southern Ocean.

Dr Richard Matear, chief research scientist in our Climate Science Centre, believes these observations demonstrate how events on land have a direct impact on our oceans.

“The phytoplankton blooms observed in the iron-enriched Southern Ocean is a real-world experiment. It shows the connectedness between the land and ocean on a global scale,” Richard said.

Our recent blog explains how iron improves anaemic oceans.

ACCESSing a climate model

Together with the Bureau of Meteorology (BOM), Australian universities and international collaborators, we developed the Australian Community Climate and Earth System Simulator (ACCESS).

ACCESS is a fully coupled earth system model. It integrates the land, the ocean, atmosphere and ice.

“Earth systems modelling is helping us understand the connectiveness of land and ocean ecosystems and atmosphere. The work helps us unravel the links between bushfires, marine ecosystems and the climate,” Richard said.

“While the bushfires had a destructive impact on terrestrial ecosystems, the fall-out effects of the bushfires enriched the iron availability in the ocean causing phytoplankton to flourish.”

Modelling for a changing climate

Experts predict more drought and extreme events as we face a warming climate.

More frequent bushfires, which release vast volumes of CO2 into the atmosphere, may also drive climate change and increase the risk of bushfires.

One surprising reflection may be that an event that caused such widespread devastation on land has a beneficial side effect of generating extraordinary productivity of life in our ocean.

Read more about our work on nature.com

25th September 2021 at 11:52 am

The logic of this observation, – that bushfires can be seen to benefit the oceans, – means that stopping bushfires, and removing bushland so it can’t burn, decreases the frequency of this benefit. Will this over time damage the health of the oceans? Has it damaged it already?

17th September 2021 at 2:10 pm

Indeed! At last, a ‘positive effect’ (a carbon-fixing negative feedback) from global warming. And expect whales to play their part in spreading the fertilizer. On the other had: >“Iron fertilization by the 1997 Indonesian wildfires was sufficient to produce the extraordinary red tide,” the authors wrote, “leading to reef death by asphyxiation.” / Wildfire smoke can also cause algae to balloon in freshwater rivers and lakes. “It usually causes a really big bloom response because [the algae] is just sitting there getting fertilized in the sun,” Kramer said. In these cases, however, it’s typically phosphorus rather than iron that the algae need to bloom, Hamilton said. < http://www.jstor.org/stable/3834840