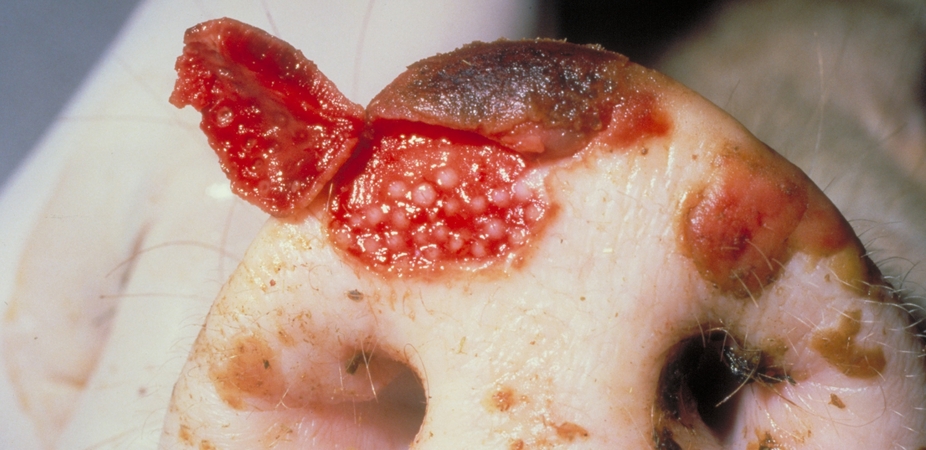

Foot and mouth disease wreaks havoc on the economies of countries where it breaks out.

By Wilna Vosloo, Principal investigator FMD risk management.

Co-authored by Dr Juan Lubroth, Chief Veterinary Officer, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

Australia has been free of foot and mouth disease since 1872, but it is still considered the most serious biosecurity threat to Australia’s agricultural industries. A widespread outbreak could cost the economy more than A$16 billion in the first 12 months.

Can foot and mouth disease actually be controlled? We think so, and we can learn a lot from how rinderpest – a highly virulent cattle plague – was eradicated.

A model for eradication

Even before the 2011 global declaration of freedom from rinderpest by the United Nations, many were asking what animal disease we could focus on next. Rinderpest was only the second virus to be globally eradicated, after smallpox.

For centuries, rinderpest devastated cattle and buffalo populations in Europe, Asia, the Middle East and Africa. It led to the downfall of armies, caused rural famine and created inestimable hardship.

The disease was not restricted by national borders: international coordination was fundamental for managing, controlling and finally ridding the planet of the virus.

Rinderpest’s reintroduction into Europe led to the establishment of a coordinating authority, the World Organisation for Animal Health, in 1924. When the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations was created in 1945, their charter to improve food and nutrition across the globe could only be realised by fighting devastating livestock diseases such as rinderpest and foot and mouth disease.

The tools for managing foot and mouth disease can be used to bring other benefits.

After decades of research and significant investment, rinderpest was isolated to only a handful of geographical areas by the late 1990s. The last outbreak was reported in 2001.

The rinderpest success story makes it clear there are three things needed if you are to eradicate an animal disease. You need political will, veterinary and local knowledge about how the disease spreads, and adequate tools (such as diagnostic assays and quality vaccines) for intervention.

These factors apply to many animal diseases, so control does not need to focus on one disease alone. Investment in improved veterinary services, for example, doesn’t just apply to disease elimination; it benefits animal health, community livelihoods and a country’s whole economy.

Can we control and eliminate foot and mouth disease?

As with rinderpest, tackling foot and mouth disease needs a global approach. Recent outbreaks in previously disease-free countries show that a piecemeal approach isn’t working: we must control the disease at source, in the places where the virus is endemic.

But disease-free countries also have to invest in their neighbours’ efforts to control and eliminate the disease. Australia is investing in neighbouring countries such as Indonesia and the Philippines, helping them with control strategies, laboratory facilities, and staff training through CSIRO and AusAID. Those countries are now free of foot and mouth disease.

Once a country is free of foot and mouth disease it can take advantage of lucrative trade with other disease-free countries. This trade isn’t just in animals, milk and meat, but also in genetics. But it takes millions of dollars to maintain freedom from foot and mouth disease, and to keep those market opportunities – worth billions – open.

Meanwhile, resource-poor countries are devastated by the effects of foot and mouth disease: reduced milk quantity and quality, weight loss and severe lameness. They are further crippled by unploughed fields, inability to transport produce to market for sale and loss of available food and quality nutrients for humans.

Unfortunately, countries where such debilitating diseases are circulating usually also have competing priorities in other sectors such as human health, education, governance and maintaining civil and political stability.

We know we have the tools, the diagnostic ability and enough knowledge about disease transmission to take on foot and mouth disease. So, globally, can we tackle the threat in endemic settings head on?

Improving practises at farm level is a good first step

There is much work to be done. But rather than focusing specifically on eradicating foot and mouth disease, countries where the disease exists could start by improving on-farm biosecurity generally.

They should improve production practises and hygiene, thereby increasing efficiency in milk and meat production, and improving the way they manage natural resources.

This can spread benefits to other areas: child and maternal care, nutrition and hygiene for the farmers and communities around the world. Boosting veterinary services and information sharing provides better health care and builds trust with trading partners.

If we took this approach, we would certainly reduce the effect of production and trade-related diseases, as well as a multitude of diseases humans can get from animals and food. Such a holistic strategy would also increase access to quality drugs and veterinary vaccines across the myriad of microbial threats, and improve the availability of high quality nutritious foods.

It is therefore not possible to focus on only one disease when embarking on disease eradication or control. We need a global approach – targeted and tailored to the prevailing social and economic conditions – against those diseases that affect livelihoods, human health and global-to-local trade opportunities.

With significant effort and investment, control and eradication are possible – not just of foot and mouth disease, but of all high-impact diseases that threaten today’s and tomorrow’s world.

This article was originally published at The Conversation. Read the original article.