What will Antarctica look like in the year 2070, and how will changes in Antarctica impact the rest of the globe? The answer to these questions depends on choices we make in the next decade, as outlined in our accompanying paper, also published today in Nature.

Read more:

Ocean waves and lack of floating ice can trigger Antarctic ice shelves to disintegrate

Our research contrasts two potential narratives for Antarctica over the coming half-century – a story that will play out within the lifetimes of today’s children and young adults.

While the two scenarios are necessarily speculative, two things are certain. The first is that once significant changes occur in Antarctica, we are committed to centuries of further, irreversible change on global scales. The second is that we don’t have much time – the narrative that eventually plays out will depend on choices made in the coming decade.

Change in Antarctica has global impacts

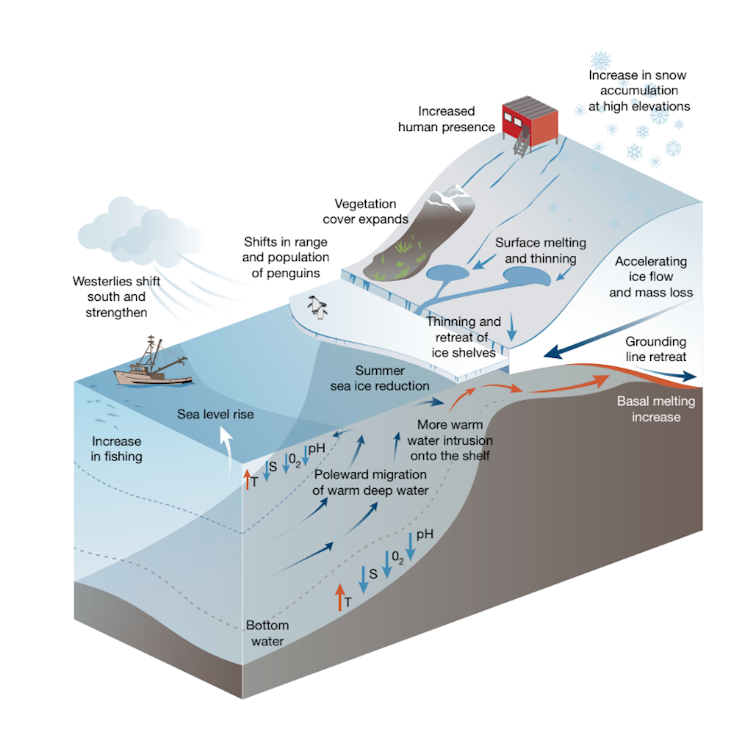

Despite being the most remote region on Earth, changes in Antarctica and the Southern Ocean will have global consequences for the planet and humanity.

For example, the rate of sea-level rise depends on the response of the Antarctic ice sheet to warming of the atmosphere and ocean, while the speed of climate change depends on how much heat and carbon dioxide is taken up by the Southern Ocean. What’s more, marine ecosystems all over the world are sustained by the nutrients exported from the Southern Ocean to lower latitudes.

From a political perspective, Antarctica and the Southern Ocean are among the largest shared spaces on Earth, regulated by a unique governance regime known as the Antarctic Treaty System. So far this regime has been successful at managing the environment and avoiding discord.

However, just as the physical and biological systems of Antarctica face challenges from rapid environmental change driven by human activities, so too does the management of the continent.

Antarctica in 2070

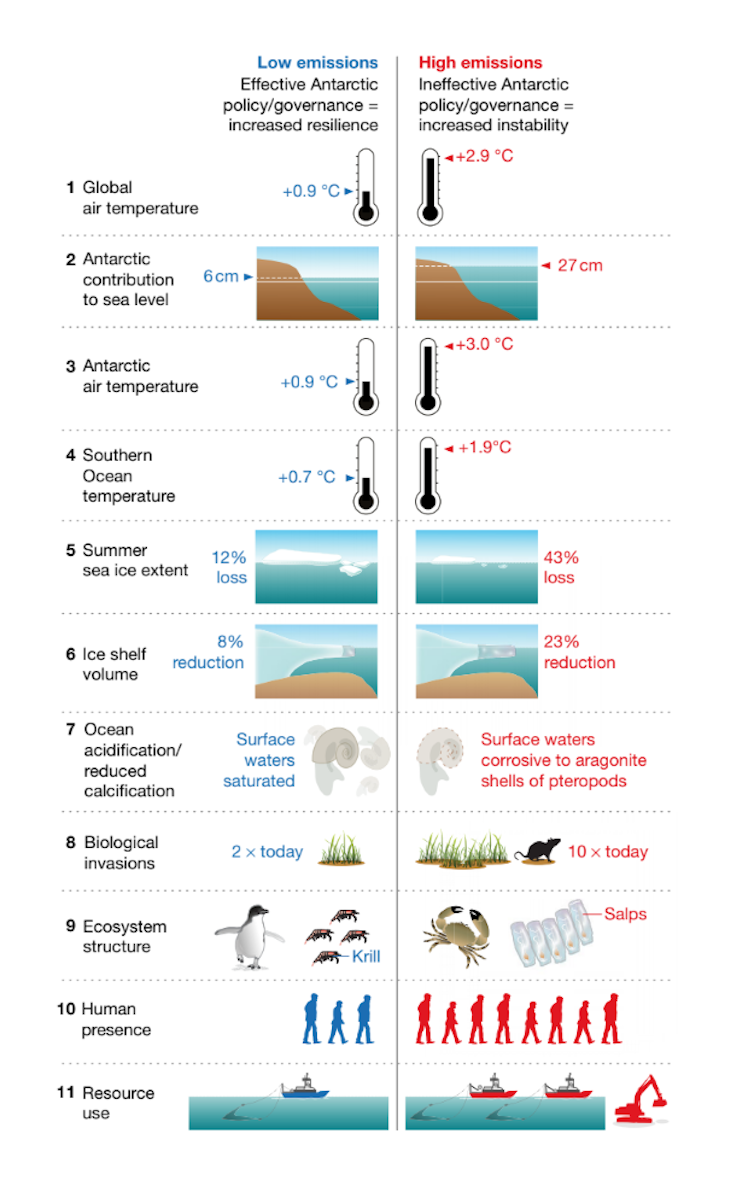

We considered two narratives of the next 50 years for Antarctica, each describing a plausible future based on the latest science.

In the first scenario, global greenhouse gas emissions remain unchecked, the climate continues to warm, and little policy action is taken to respond to environmental factors and human activities that affect the Antarctic.

Under this scenario, Antarctica and the Southern Ocean undergo widespread and rapid change, with global consequences. Warming of the ocean and atmosphere result in dramatic loss of major ice shelves. This causes increased loss of ice from the Antarctic ice sheet and acceleration of sea-level rise to rates not seen since the end of the last glacial period more than 10,000 years ago.

Warming, sea-ice retreat and ocean acidification significantly change marine ecosystems. And unrestricted growth in human use of Antarctica degrades the environment and results in the establishment of invasive species.

In the second scenario, ambitious action is taken to limit greenhouse gas emissions and to establish policies that reduce human pressure on Antarctica’s environment.

Under this scenario, Antarctica in 2070 looks much like it does today. The ice shelves remain largely intact, reducing loss of ice from the Antarctic ice sheet and therefore limiting sea-level rise.

An increasingly collaborative and effective governance regime helps to alleviate human pressures on Antarctica and the Southern Ocean. Marine ecosystems remain largely intact as warming and acidification are held in check. On land, biological invasions remain rare. Antarctica’s unique invertebrates and microbes continue to flourish.

The choice is ours

We can choose which of these trajectories we follow over the coming half-century. But the window of opportunity is closing fast.

Global warming is determined by global greenhouse emissions, which continue to grow. This will commit us to further unavoidable climate impacts, some of which will take decades or centuries to play out. Greenhouse gas emissions must peak and start falling within the coming decade if our second narrative is to stand a chance of coming true.

If our more optimistic scenario for Antarctica plays out, there is a good chance that the continent’s buttressing ice shelves will survive and that Antarctica’s contribution to sea-level rise will remain below 1 metre. A rise of 1m or more would displace millions of people and cause substantial economic hardship.

Under the more damaging of our potential scenarios, many Antarctic ice shelves will likely be lost and the Antarctic ice sheet will contribute as much as 3m of sea level rise by 2300, with an irreversible commitment of 5-15m in the coming millennia.

![]() While challenging, we can take action now to prevent Antarctica and the world from suffering out-of-control climate consequences. Success will demonstrate the power of peaceful international collaboration and show that, when it comes to the crunch, we can use scientific evidence to take decisions that are in our long-term best interest.

While challenging, we can take action now to prevent Antarctica and the world from suffering out-of-control climate consequences. Success will demonstrate the power of peaceful international collaboration and show that, when it comes to the crunch, we can use scientific evidence to take decisions that are in our long-term best interest.

Steve Rintoul, Research Team Leader, Marine & Atmospheric Research, CSIRO and Steven Chown, Professor of Biological Sciences, Monash University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

8th August 2018 at 4:50 pm

I’m no expert…just your average punter reading the everyday news, but listen to the nay sayers. If there wrong we are all stuffed. By changing our ways with consumption, pollution, carbon output, other gases output and massive population control of humans….so basically being sustainable, there can only be benefits for the entire planet even if climate change isn’t real. I know which theory I’m supporting!!!!

11th July 2018 at 12:52 pm

New Zealand research has shown the Ross Ice Shelf to be stable and may be expanding. How does the CSIRO model explain that?

5th July 2018 at 9:42 am

0.01% of total mass and the study has error of +51%. This sounds like gut-feel. The results could also be classified as impossible and unlikely. Based on these results the CSIRO predicts sea level rise of 60cm-1metre by 2100. Seriously you need to explain to the general public the error analysis and probability. This is sensationalised junk science (Nature has become uncreditable) in my mind like a snow ball perpetuated by bias and misleading assumptions. At this point in time based on hard facts it’s better to flip a coin so we can all agree.

11th July 2018 at 1:45 pm

Hi there, David,

Here’s a response from our researcher:

‘The following four points are relevant to this comment:

1. The statement that Antarctica has lost 0.01% of its mass is based on 25 years of satellite measurements of ice volume, flow and gravitational attraction and estimates of snowfall on the continent. The fact that this combination of instruments can measure changes in the mass of the entire Antarctic Ice Sheet to within an error of about 50% is remarkable.

2. Whether 0.01% is a big or small number depends on what you are talking about. The Antarctic Ice Sheet is so vast (a mass of about 2.7 x 1018 kg) that even a small change in mass of 0.01% raises sea level around the entire globe by a measurable amount.

3. However, the most important aspect of the study is the fact that the loss of mass from the Antarctic Ice Sheet is accelerating with time. For example, the loss of mass from West Antarctica tripled between the first and last five-year period considered. It is important that we continue to track changes in the Antarctic Ice Sheet to see if this tendency continues and to understand what factors are driving the increase in mass loss.

4. The estimate of 60 cm to 1m of sea level rise by 2100 is not based on extrapolation of these measurements of change in the past 25 years. They are based on the most recent published estimates of the future behaviour of the Antarctic Ice Sheet, based on models that represent ice sheet flow and interactions between the atmosphere, ocean, bedrock and the ice sheet.’

Jesse

CSIRO Social Media Team

26th June 2018 at 11:08 am

Please make plain what percentage of the total ice mass in Antarctica is “3 Trillion tons”.

I’m thinking it’s a very small percentage (and is it distinguishable from noise and natural climate variation??). If so, how does this very small percentage warrant the “time is running out” headline?

This headline and article seem like a sensationalist propaganda stunt unbecoming of the CSIRO (or any scientific body).

29th June 2018 at 2:21 pm

Hello,

We asked one of our scientists to help answer your question:

“Three trillion tons is about 0.01% of the total mass of the Antarctic Ice Sheet. This doesn’t sound like much. But even this small fraction is sufficient to have already raised sea level around the entire globe by 8 mm. More importantly, the rate of mass loss is accelerating. The most recent estimates suggest an Antarctic contribution to sea level of between 60 cm and 1 m by 2100, and sea levels will continue to rise in the centuries to come. The contribution from thermal expansion and mass loss from Greenland needs to be added to the Antarctic contribution to get the total sea level rise.

If society decided that it was preferable to follow a low emissions pathway (e.g. as needed to meet the Paris Agreement target of limiting global warming to less than 2°C above pre-industrial temperatures, and to minimise the risk of large sea level rise from melting ice sheets), then action would need to be taken very soon. Science and economics show that after another decade of continued high emissions, it becomes virtually impossible to follow the low emissions pathway. The paper makes the point that decisions made today have long-term consequences.”

Cheers,

Eliza – social media team

21st June 2018 at 8:43 pm

It’s just now worthwhile to respond to those comments by pjcarson2015. If (s)he doesn’t get it now (s)he never will.