The 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill is often cited as the worst environmental disaster in U.S.A’s history.

The Deepwater Horizon oil spill of 2010 was the largest and most destructive toxic marine spill in history. Almost 4.9 billion barrels of oil were discharged into the Gulf of Mexico. The slick wreaked widespread havoc over oceans, beaches, wetlands and estuaries.

The spill covered the habitat of more than 8,300 species of fish, crustaceans, birds and other wildlife. In the months after the spill, the area contained 40 times more polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) than it did before. PAHs include carcinogens and chemicals dangerous to human and animal life. This was a disaster on a monumental scale.

Remediation efforts were intense but laborious, and in many cases had side-effects on the environment.

Seabird losses from the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill estimated at hundreds of thousands. Photo: Office of Governor Jindal/ Louisiana Gohsep.

Sci-fi or synthetic biology?

Imagine an army of synthetic, jellyfish-like organisms that could be deployed to ‘hunt and kill’ pollutants like PAHs. They could be released in marine environments after toxic spills, breaking down toxins down as they move through the affected area.

They would be immense in number, but non-replicating. Able to absorb the toxic chemicals before they cause any great harm.

While it might seem like a sci-fi fantasy, this solution is actually closer to reality than you would think – thanks to the wonders of synthetic biology.

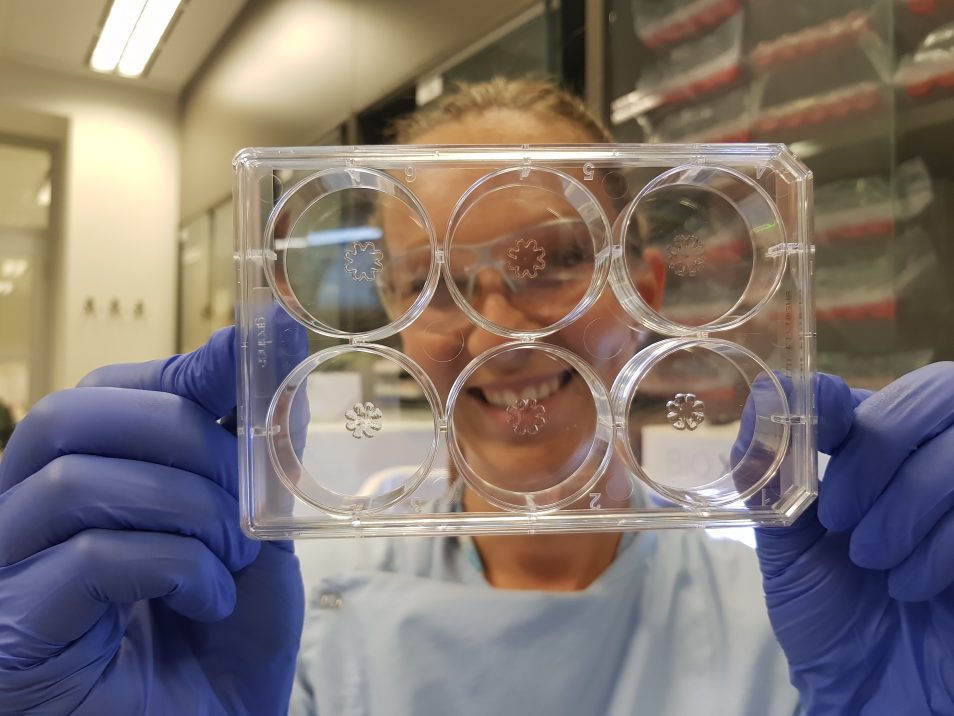

Dr Nina Pollak holding up printed prototypes of the synthetic jellyfish.

Synthetic biology to the rescue

Synthetic biology is a rapidly growing research area and industry. It brings together principles from biology and engineering together to design and construct new biological entities (such as enzymes, genetic circuits, and cells) or to redesign existing biological systems.

Synthetic biology is used for important applications like bioenergy, sustainable biomaterials, new therapeutics, biosensors, and food production.

We see a great future in synthetic biology, so we set up the Synthetic Biology Future Science Platform (SynBio FSP). One of our most exciting new projects is to create a multicellular structure, a bit like biological tissue, which can move and sense certain things in marine environments.

A (multicellular) tissue for your (toxic spill) issues

We want to create a new multicellular structure to detect toxins in aquatic environment. Once it has detected the toxins, it will mimic natural processes from our body’s detoxification organ, the liver. It will then produce animal liver enzymes that break down the toxins.

The multicellular structures could be used to restore the balance of nature in the wake of pollution incidents.

“It’s a non-invasive, environmentally sustainable solution for toxic spills. They could even be preemptively deployed in areas that are at risk for toxic spills without impacting the environment around them,” says project lead and SynBio FSP future fellow Dr Nina Pollak, who is also a researcher at the University of the Sunshine Coast, where the research is undertaken.

So should we worry about the possibility of a sea of self-replicating pseudo jellyfish going rogue and invading the ocean, nanobot–style?

No, says Nina. “The pseudo jellyfish will be fully biodegradable and not able to reproduce. There may even be the possibility to implement a ‘kill switch’ into them for biocontainment.” In other words, our scientists could create a ‘self-destruct’ mechanism in these toxin-swallowing synthetic jellies.

“We’re still in the proof of concept stage, but we hope that one day this technology could be used on a wide-spread scale,” said Nina.

28th June 2019 at 10:40 pm

wanted to meet with Nina to discuss doing something similar with marine microplastics… can you convey my interest to her – I will be in Oz in a few weeks and would like to speak with Nina about this

18th May 2019 at 10:43 am

Why don’t we grow real jellyfish and use them? I know that is impractical but more synthetic products in the ocean? No thanks.

20th May 2019 at 5:27 pm

Hi Chris,

Thanks for your interest in this story. To answer your questions:

– Normal jellyfish can’t do the job. The wild type jellyfish would need to be mutated/engineered to do so. This would mean GMO – genetically modified organisms, which are contentious. While people study jellyfish and their genetic manipulation, we do not know enough to easily manipulate them, or to use GMO jellyfish.

– On the issue of introducing “synthetic” material: synthetic means imitating a natural product. In our case this means biological tissue and gelatin-based ink. These are two components that we often find in nature.

We hope this answers your questions.

Kind regards,

Kate from the CSIRO communications team.

17th May 2019 at 8:37 pm

Why do oil companies never have floating barriers ready to deploy in case of spill? Seems a very serious mismanagement. They get sued but that doesn’t fix the problem if judges made lack of due care insetting up the oil spill protocols part of the costs awarded against the perpetrators things might change

17th May 2019 at 4:03 pm

I have also read “Do you have ….”.It sounds great and not one of the great ideas that quietly vanish. But my problem is that our government (both type) is for “small government; private enterprise can do everything better than bureaucracy”. If it succeeds, this has bulk potential. China is a good private enterprise place, ideal to turn laboratory into factory.

16th May 2019 at 3:04 pm

So what happens when jellyfish predators come along and eat these “toxic swallowing synthetic jellyfish” ?

17th May 2019 at 4:14 pm

Hi Allan,

That’s a great question. The project is still at ‘proof of concept’ stage and more research needs to be done. Analysing the effect on marine life is one of the next steps. However, the ‘jellyfish’ are created from biodegradable gelatin-based ink and could potentially be an actual protein source for animals.

Thanks,

Kate from the CSIRO communications team.