In the wise words of John Lennon, ‘Power to the people, right on’.

Truer words have never been spoken and in this instance, we are talking the buzz-ness of bees. No, we’re not pollen your leg. We need people power to save our pollinators.

It’s true, bee puns really sting. Ok, we’ll stop now.

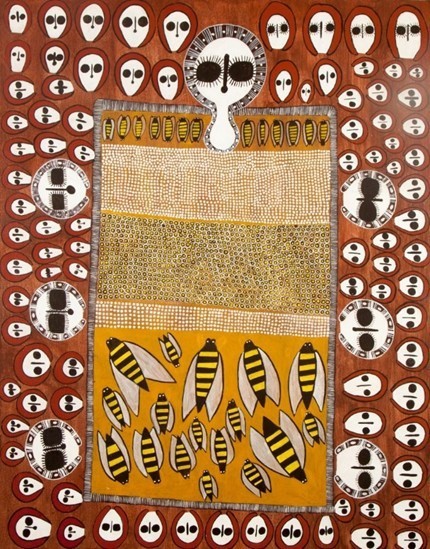

Bees are a vital part of our quality of life and in ecosystems globally. Image: David McClenaghan

Let’s face it, honey is like liquid gold, this sugary nectar of the gods sweetens even the sourest of souls. Luckily for us, honey isn’t the only gift our buzzing buddies provide us.

Bees are actually a vital part of our quality of life. Through pollination, they contribute to our sustainable livelihoods, maintenance of ecosystem health and function, food production, and cultural, spiritual and social values.

Whilst bees aren’t the only pollinators, they do play an essential part in ecosystems all over the world. They are the main pollinators of our food and without them, here’s the real stinger, we could see devastating effects on our food production.

As awareness of the importance of our sweet saviours is certainly growing amongst the public, efforts to protect and stop the decline in bee populations around the world have generally been limited to increased land conservation reserves.

Conservation science has often neglected cultural knowledge systems, values and approaches. However, a recent global study has found that people are essential to conserving the pollinators that maintain and protect biodiversity, agriculture and habitat. In particular, Indigenous communities who occupy large parts of our planet including many high biodiversity areas.

“What we found is that the best way to protect pollinators is to support those people whose cultural, spiritual and economic lives are tied to them.” lead researcher Ro Hill said.

In a world first, the global pollination assessment included input from Indigenous pollinator experts and scientists from around the world who were able to contribute local indigenous knowledge, practices and belief to help shape future policies that support biocultural conservation.

“Where local communities rely on bees as a source of honey and wax, they will not just protect the bees, their habitat and their nectar sources, they will also acquire detailed knowledge of their biology and ecology that will contribute to long-term, sustainable management of those resources,” Ro said.

Bee-lieving in the power of Indigenous knowledge

Indigenous peoples and local communities have many unique practices to keep bees—by far the most important food pollinator—and collect honey, like the Gurung people of Nepal whose innovative rope ladder technology allows them to harvest foster bees in-situ, rather than moving them to hives.

Gurung man collecting the Apis dorsata laboriosa honeycombs on cliffs in Nepal. Image: Andrew Newey

What’s more, their philosophies on biocultural diversity recognise the continuing co-evolution and adaptation between people and nature. This co-evolution has generated ecological knowledge, spiritual beliefs and practices across generations, such as the Wandjina-bee honey links. According to Ngariniyin artist Sandra Mungulu, “Wandjinas (ancestral beings from the Dreaming, present in the landscape today) keep the countryside fresh and healthy which allows the native bees to produce high-quality Waanungga, bush honey”.

‘Wandjina and Waanungga’, artist Sandra Mungulu (b. 1960), acrylic on canvas. Sandra explains “The Wandjinas (ancestral beings, present in the landscape today), keep the countryside clean for the bees to make Waanungga (honey).” © Sandra Mungulu/Copyright Agency, 2019.

These and other practices were highlighted in the Assessment.

Policies for the pollinators

Researchers say the best policies to protect bees recognise these values, strengthen indigenous and community-conserved areas and support diversified farm systems, while it’s a step in the right direction, there’s still a long way to go.

As the paper concludes: “Further efforts are needed to promote and increase the exchange and integration of knowledge on pollinators and pollination between the scientific world and indigenous pollinators and local communities working towards common conservation goals.”

Read more in Nature Sustainability