How do you like your veggies? Are you a boiler, a roaster, a steamer or maybe even a stir-fryer?

There’s no denying the goodness of vegetables. They provide essential nutrients for our everyday health and wellbeing. But can the way we prepare them alter how much nutrition we get out of them? The short answer is yes – and it’s all to do with their structure.

Carrots and turnips

When it comes to maximising the nutrition of fruit and vegetables, structure is key. Image: Flickr/meg’s my name

For generations, many Aussies soaked their veggies in water, boiling them till they were soft and straining off the water they were cooked in. But this method leaches most of the vitamins and nutrients out of the plant and doesn’t leave much goodness other than fibre.

Vitamin C, for instance, is a delicate food micro-nutrient that’s essential for growth and development. But given that it’s water-soluble, it can be easily damaged by overcooking.

So is it better to eat our veggies raw? Snacking on a carrot when the nibbles hit during the day is more nutritious than eating over-cooked veg, but it’s not always the best way to make the most of the vitamins veggies have to offer.

Our research into food structures, digestion and health suggests a food’s structure has a huge impact on how nutrients are released in our bodies from the food.

Fruit and vegetables are built from millions of plant cells that lock up their vitamins in what’s called a ‘cell wall’ structure. For instance, when a carrot is fresh and raw, the cell walls are firmly attached to each other. This is partly what gives carrot its crunch.

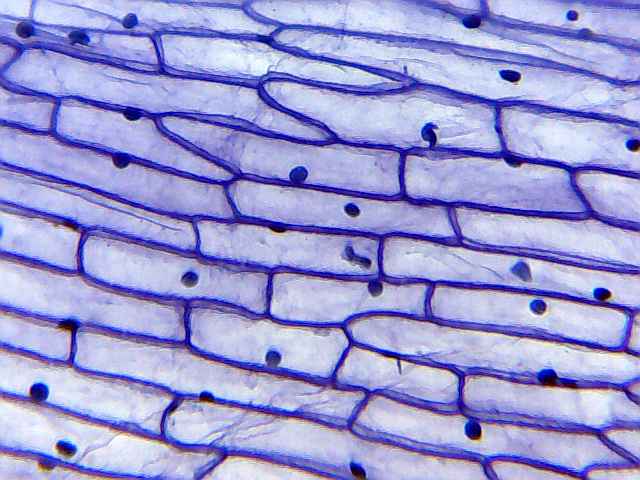

The typical cell wall structure of a plant. Image: Flickr/Yersinia

Based on this work, we’re helping create a healthier Australian food supply by incorporating more positive nutrients – like vitamins and fibre from vegetables – into our everyday processed foods such as bakery products and yoghurts.

But in the mean time, how can we make the most of our veggies?

Gentle steaming with a very small amount of water, or even grating a fresh veggie like carrot, breaks the plants cell walls and makes the inherent nutrients more ‘bio-available’ – that is, available for absorption by the body as we digest it. Adding the water your veg is cooked in to your meal will help maximise the vitamins available for digestion.

The same goes for fruit. Fruit blitzed into smoothies, pureed and used in sauces and desserts breaks the cell walls and increases the bio-availability of many nutrients – but make sure you eat the pulp as well, as it contains valuable nutrients and fibre.

In many cases, veggies or fruit such as tomatoes can provide better nutrition processed than raw – as is the case for tinned tomatoes and pasta and passata sauces.

The antioxidant lycopene can be more easily absorbed by the body in cooked tomato products, compared with raw tomatoes. Image: Flickr/ devlyn

Time to lift the lid. The antioxidant lycopene can be more easily absorbed by the body in cooked tomato products compared with raw tomatoes. Image: Flickr/devlyn

Of course, some vegetables like potatoes have to be cooked to be able to eat them at all. But a mixture of raw and gently cooked vegetables and fruit in our diet is key to maximising their nutritional value.

We’re getting together with the food industry and researchers this week to talk more about the increasing awareness of food structures and what they mean for the bio-availability of nutrients at the Food Structures, Digestion and Health Conference.

26th October 2017 at 12:56 pm

Worth watching ABC Catalyst’s last two programs about the gut microbiome which if healthy, is able to break down the otherwise indigestible cellulose. The biproducts can then be digested in the lower intestine. Good understanding of pre-& pro-biotics helps to promote a healthy gut microbiome but ultra sterile conditions in ( for example) caesarean birth can mean that babies miss out on a good dose of these important bacteria at birth.

26th October 2017 at 11:10 am

I wonder where a quick microwave with no added water fits in the mix.

11th March 2014 at 4:53 pm

At last, some scientific evidence for what is common sense. Well done team!

3rd March 2014 at 2:36 pm

This is really interesting, I’m just finding it counter-intuitive. My assumption was that chewing, followed by digestion, would easily break up cell walls to release the nutrients inside. If that’s not the case, and we need to make sure the cell walls are destroyed before eating, does that mean that after eating say, an uncut raw carrot, we pass the cells in tact?

3rd March 2014 at 4:37 pm

It can seem a bit counter intuitive! We lose a bit of vitamin C by cooking veg like carrot, but chewing is actually fairly inefficient and our bodies can’t break down cellulose materials. If the fibrous structure isn’t altered in some way, most of the inherent nutrients in something like a piece of uncut raw carrot will just go in one end and out the other! The advent of fire by cave man and thus cooking their food is credited with rapid human development and that’s owing to the increased bio-availability of nutrients in their food supply. Hope that helps.

Cheers,

Steph

3rd March 2014 at 8:45 pm

Thank you Steph, for the clear and informative response 🙂

21st February 2014 at 2:38 pm

Thanks for the information Dr Ingrid! I hope to read more of your writings!