Here’s a challenge: how would you go about finding something if you didn’t know what it was you were looking for? No, this isn’t an ancient riddle or one of those horrible corporate team building exercises. It’s actually a very real problem being being faced by astronomers using our newest telescope, the Australian SKA Pathfinder (ASKAP).

The Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder.

The Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder. Credit: Alex Cherney

Here’s a challenge: how would you go about finding something if you didn’t know what it was you were looking for?

No, this isn’t an ancient riddle or one of those horrible corporate team building exercises. It’s actually a very real problem being being faced by astronomers using our newest telescope, the Australian SKA Pathfinder (ASKAP).

In order to understand how galaxies form and evolve, the Evolutionary Map of the Universe (EMU) team will take a census of radio sources in the sky. Along the way they expect to find about 70 million galaxies along the way – which is a substantial increase from the 2.5 million we currently know of. But to do so means trawling through, literally, a Universe of data.

“With EMU significantly increasing the volume of phase space we’re observing, it’s more than likely we’re going to stumble across some unexpected new phenomena,” said the project’s Principal Investigator, Ray Norris.

The EMU in the sky.

The EMU in the sky. Credit: Barnaby Norris.

But with the supercomputer only sifting through data collected according to a specific selection criteria, there is a chance that these phenomena may fall through the cracks and lie undiscovered for decades, until an “open-minded researcher” suddenly recognises something odd in the data.

The truth is out there, but how would the team find it?

Well, we can tell you how: by developing a cloud computing platform that learns how to stumble across unexpected bits of science that would otherwise be ignored.

“We had a huge opportunity to analyse the data to look for outliers that might point to some new and interesting discovery, so we looked to cloud computing as a way to mine the massive amounts of data looking for any hidden gems.”

The result is the Widefield ouTlier Finder (WTF), a project to develop data mining techniques that search for phenomena beyond the limits of current astronomical knowledge.

Ray says there are three types of outliers they’re looking for. “First are the artefacts, which are important for our quality control, then there are the statistical outliers which are interesting, but the most important are the third kind of outliers – the entirely unexpected bits of science, the ones that make us stop and say – WTF?”.

“The complexity of the newest telescopes like ASKAP means that we can’t just hope to simply stumble across new phenomena, we have to actively look for it by whatever means we can, or else we’ll end up missing the most exciting science results of the future.”

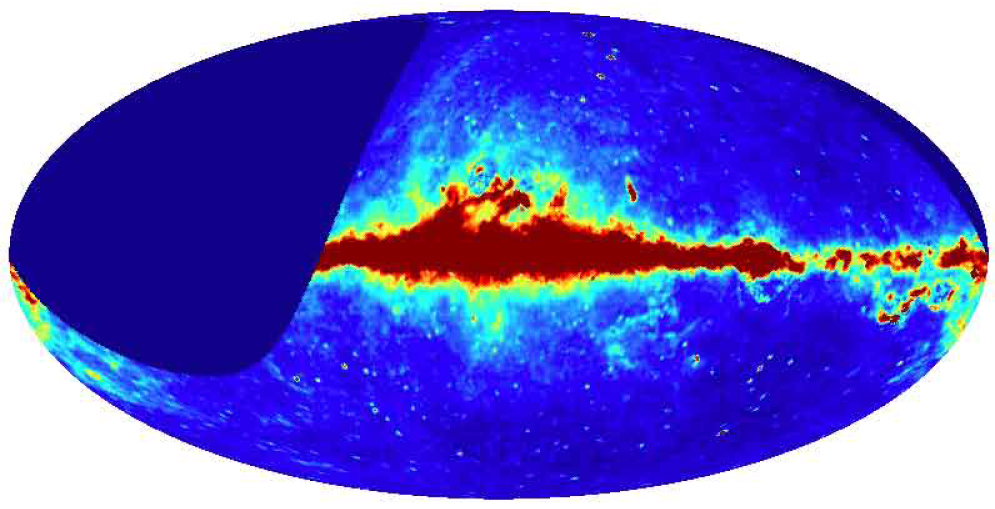

A colourful representation of the EMU sky coverage. The area in the top left is the part of the sky not covered by EMU.

A colourful representation of the EMU sky coverage. The area in the top left is the part of the sky not covered by EMU.

WTF’s cloud-based backend is hosted on Amazon Web Services servers, where the researchers are able to access software for data reduction, calibration and viewing right from their desktop. The team is currently issuing a challenge using data peppered with “EMU (Easter) Eggs” – objects that might pose a challenge to data mining algorithms. This way they hope to train the system to recognise things that systematically depart from known categories of astronomical objects, to help better prepare for unanticipated discoveries that would otherwise remain hidden.

EMU has received a grant to develop a cloud computing platform for machine learning as part of the AstroCompute in the Cloud collaboration, driven by Amazon Web Services (AWS) and the SKA Telescope. The collaboration is intended to accelerate the development of innovative tools and techniques for processing, storing and analysing the global astronomy community’s vast amounts of astronomic data in the cloud.

Pingback: A machine astronomer could help us find the unknowns in the universe

Pingback: Finding the unknowns in the universe – TopNewsPH

3rd December 2015 at 1:12 pm

Testing out the comments.