A painting of two Tasmanian tigers standing – tan coloured dog like animals with black tiger stripes on back and tail.

The Tasmanian tiger, or thylacine, was the largest known carnivorous marsupial of modern times. Wikimedia Commons: John Gould

Eighty two years ago today the last known Tasmanian tiger (Thylancinus cynocephalus) died in Beaumaris Zoo, Hobart, though it would be a further 50 years before the species was officially declared extinct.

Although the Tasmanian tiger, or thylacine, lived solely on Tasmania for its last 2,000 years, fossils dating back to the Palaeogene period indicate the species once lived on both mainland Australian and Papua New Guinea. And just like Scotland’s Loch ness and Gippsland’s elusive black panther, there have been numerous unconfirmed sightings of thylacines, both on and off the mainland, for years. There have also been recent discoveries of nests and dens, typical of thylacine nests, photographed in the 1800s—some complete with unidentified animal hair.

A hairy mystery

In 2016, a collection thought to have previously belonged to 20th Century British naturalist David Bellamy went up for auction in the United Kingdom. Within it, was a small envelope labelled “Thylacinus cynocephalus”. It contained three tan-coloured hairs.

The mystery hairs were acquired by Sydney-based amateur naturalist, Chris Rehberg. Chris has an interest in thylacines that extends to investigating whether the timid marsupial’s existence continued past its declared extinction date.

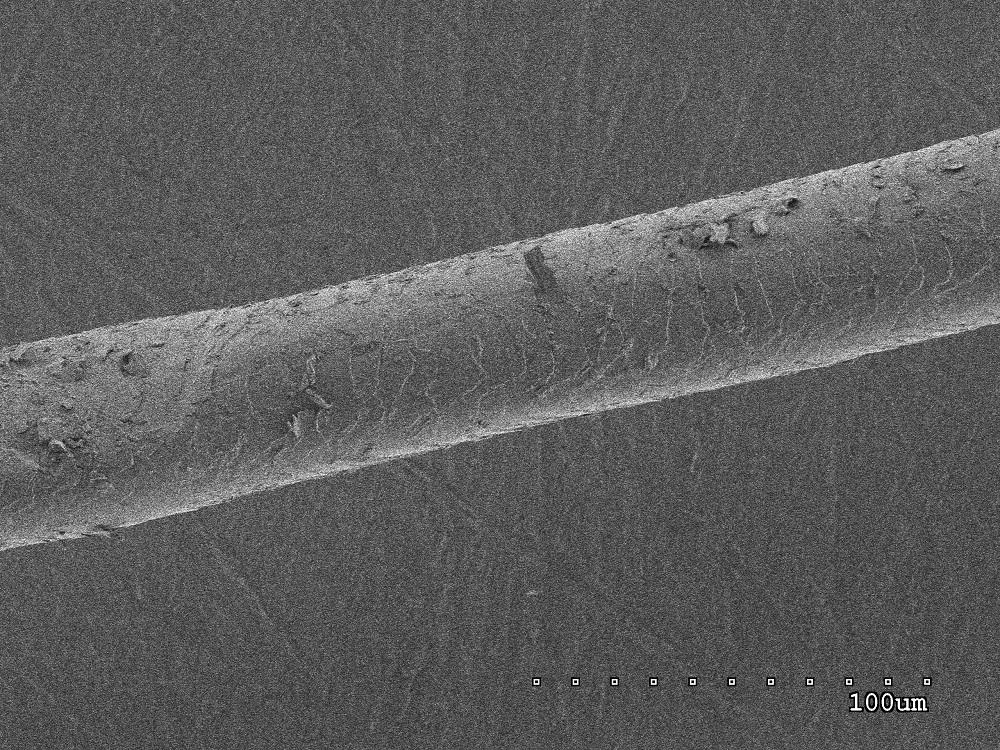

Having good micrographic evidence of thylacine hair to use as a comparison base for more recent findings would be useful in this endeavour. Thylacine hair samples can already be found in various museums around the world, however the existing analyses and black and white images were of fairly poor quality, so Chris was keen to get some photomicrographs that would allow a clearer look at details such as surface scaling and hair pigmentation.

But first Chris would need to confirm the hairs’ authenticity. He created a crowdfunding campaign to help raise the money required to purchase the necessary equipment to solve this mystery.

Putting extinction under the microscope

Microscopic image of thylacine hair.

When our microscopy team heard about Chris’ quest, their interest was piqued, and they immediately got in touch, offering the use of their equipment and expertise.

Our team studies things under the microscope day in, day out – from wool to metal alloys, and they’re very good at it! The shelves in the Geelong microscopy lab proudly display numerous collections of materials, including wool samples from nearly every sheep known to man. They even have a sample hair from the extinct woolly mammoth!

If anyone was going to determine the origin of the envelope’s contents, it was our microscopy team.

It was soon confirmed the three hairs were indeed from a thylacine. What’s more, it was discovered the three distinct hairs each represented a different part of the tiger’s pelt—guard, over and under.

This was an interesting find, because most other mammals have only two different kinds of hair distributed throughout their pelt—guard and under (or down). The thylacine’s additional over hair suggests the species may have evolved to better suit the cooler, damper climates it inhabited. Other known species to have a similar three hair structure include the Scottish highland cow.

Adding to the knowledge

Confirmation of the hairs’ authenticity, and the high quality images and analysis generated by our microscopes, means we can now add to the existing knowledge on this beautiful and unique animal, and maybe even answer some questions about thylacine’s final years on Earth.

Could the species have persisted into the 21st Century? Perhaps we’ll never know, but at least we now have some high quality data on a bona fide hair sample to compare with more recently found samples.

And the next job for our microscopy team? We’re on the lookout for a sample of Tibetan Yeti hair so they can confirm the existence of the abominable snowman!

Fun fact: In 1999 researchers at the Australian Museum attempted to clone a thylacine, à la Jurassic Park, using 100 year old female tissue samples. Although DNA was successfully extracted and genes replicated, the project was scrapped in 2005 after researchers deemed the DNA of too poor quality to work with.

7th September 2018 at 5:03 pm

Fascinating research ….. I havce a personal interest in the Thylacine, as I thought I saw one on the West Coast of Tasmania in I think about 1953/4. Dad informed me it could not have been one as they were extinct, and I as a ten year old, took it at face value. But I have thought about it often over the years, and still can only think it was the Tasmanian Tiger.