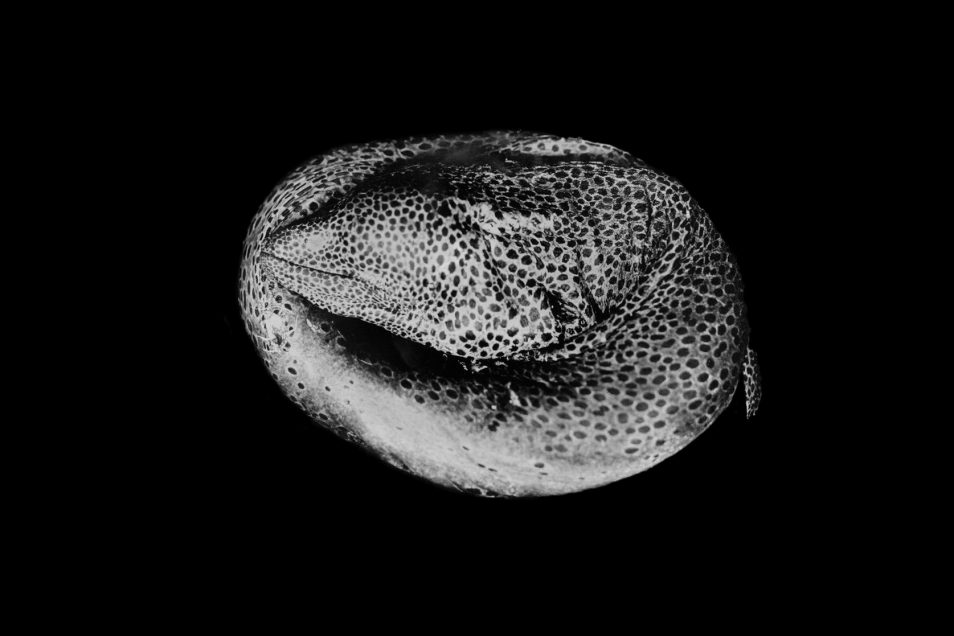

Gymnothorax isingteena, the Spotted Moray. Tintype photograph by Phillip England. Digitally enhanced by Carlie Devine.

Spotted Moray. Tintype photograph by Phillip England.

A fish’s colours can be critical for identifying its species, especially for species like tropical wrasses, whose colouring differs between males, females and juveniles.

When fishes are preserved in natural history collections they lose much of their colour, becoming dull shades of grey and brown when they are first fixed in formalin and then stored long-term in ethanol. Yellows, oranges, reds and greens all fade away, but darker browns and blacks tend to remain. To capture the original colours of the fishes in our collection, we photograph specimens as soon as they are collected.

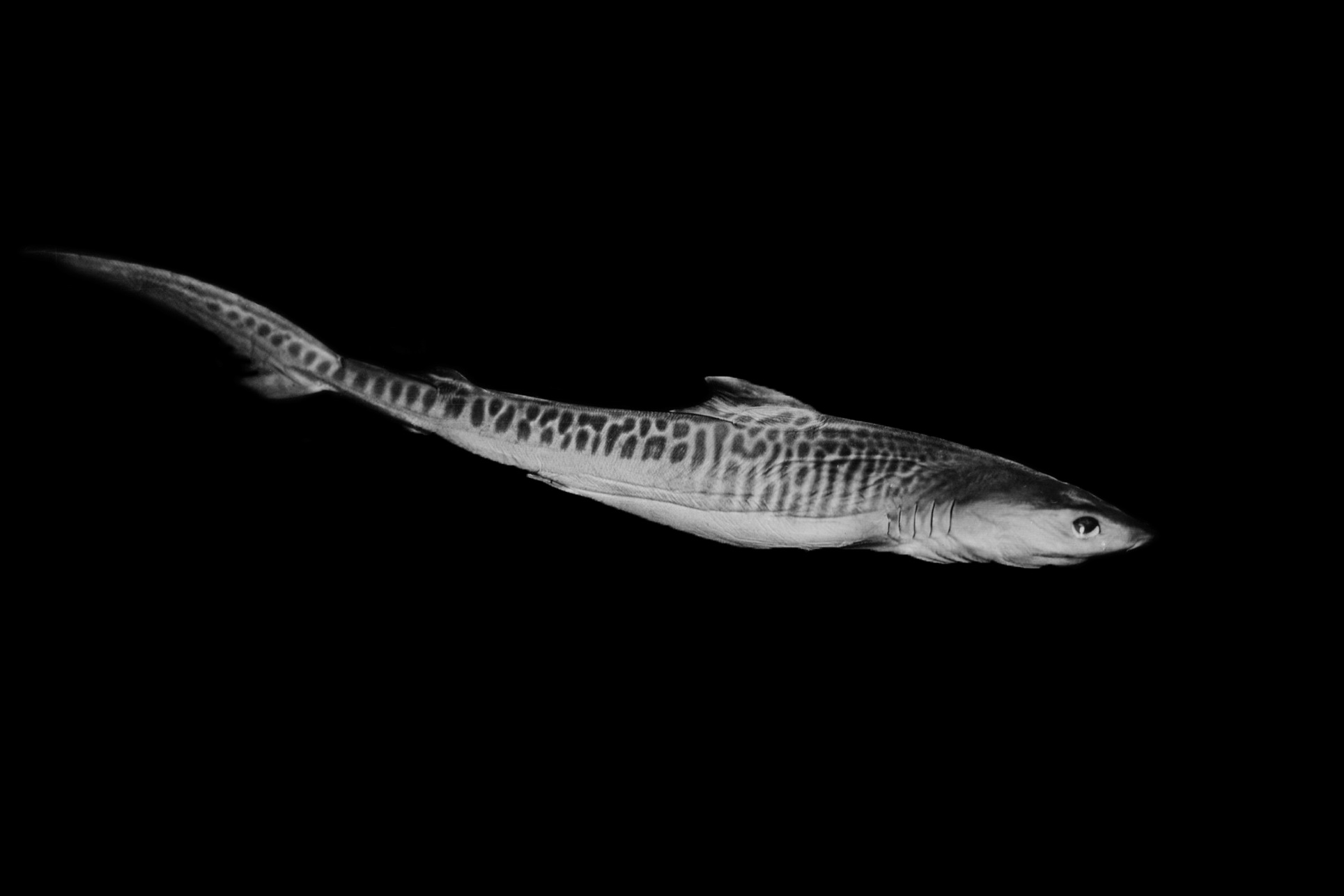

Along with colour, features like length, shape and skeletal details are all important for identifying a fish’s species. We use photomicrography to record small details such as shark skin dentacles, which cover the entire body of a shark like the scales of bony fishes and can be as small as 2 mm long. We also take x-rays of our fish specimens if the skeletal details, like the number of vertebrae, are important in telling one species from another.

At the molecular level, we can read a fish’s DNA barcode and compare this DNA sequence to a reference library, Barcode of Life, to determine its species.

Phillip England photographing an Ornate Angelshark, one of nearly 156,000 specimens of the Australian National Fish Collection. Photo credit: Dan Gledhill

The nearly 156,000 specimens in the Australian National Fish Collection provide physical evidence of a fish species occurring in a specific place at a specific point in time. The collection is an invaluable resource that supports conservation and fisheries management in Australia and the region. It can help reveal the impact of fishing or climate change on fish populations and help scientists assess which species may be vulnerable.

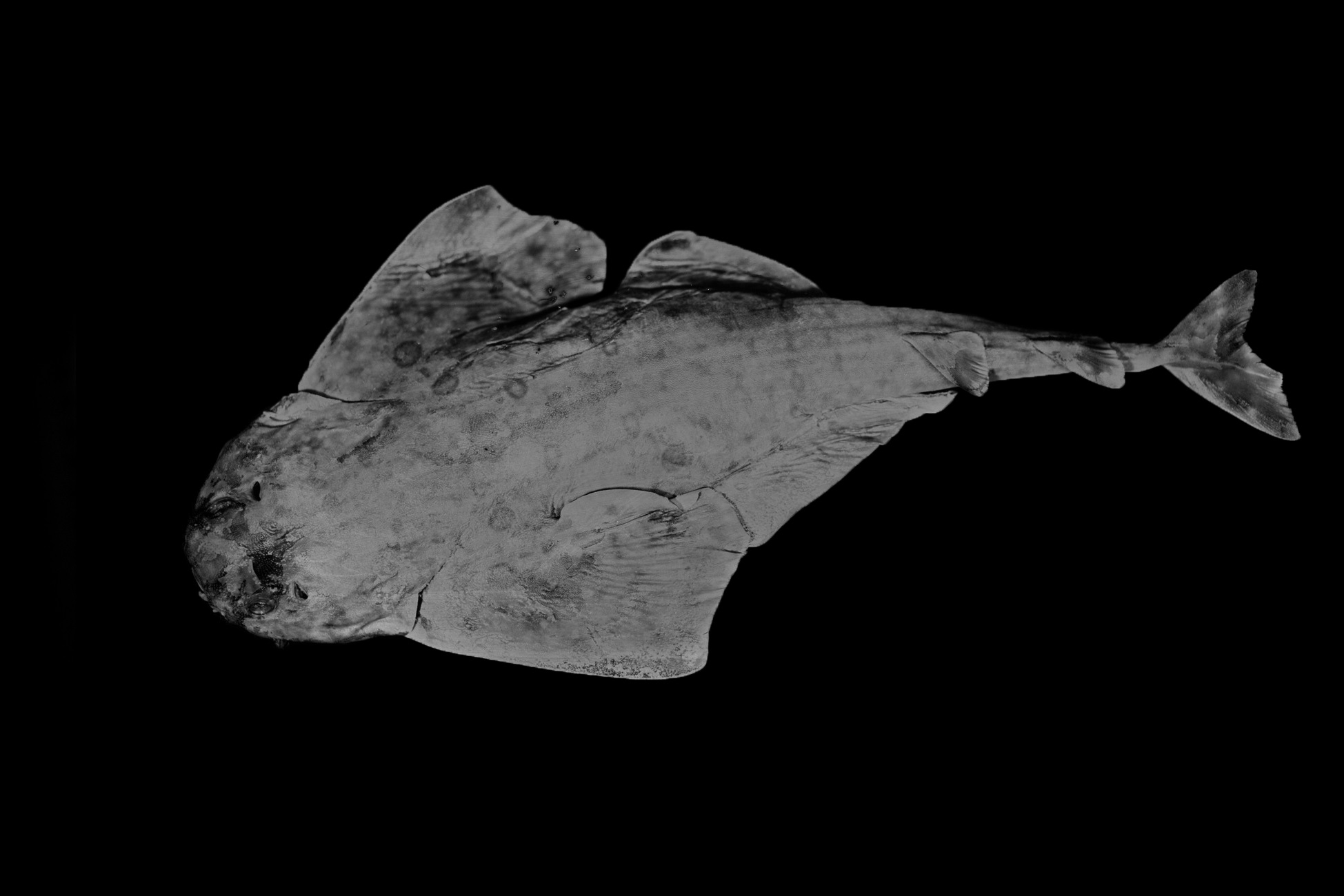

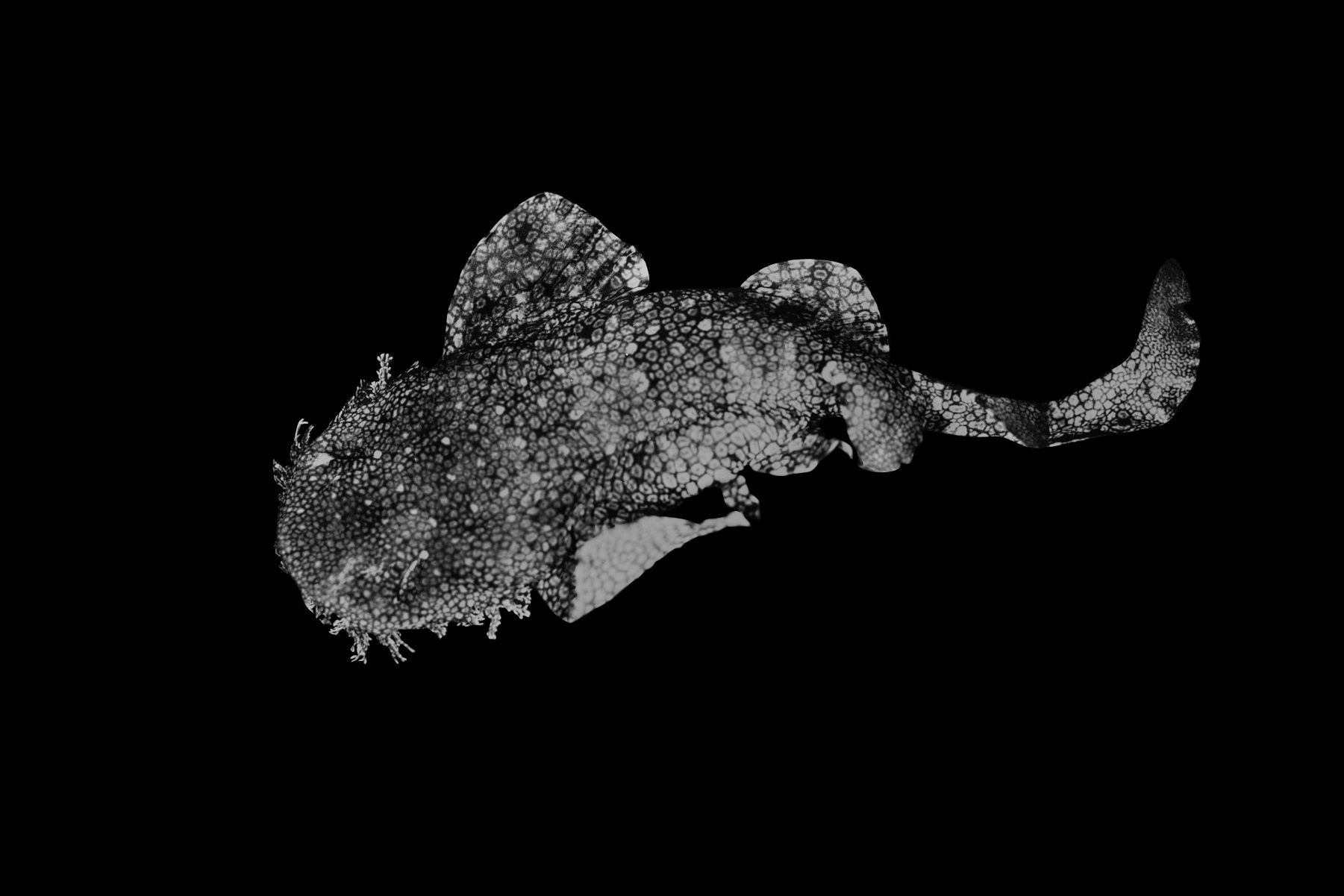

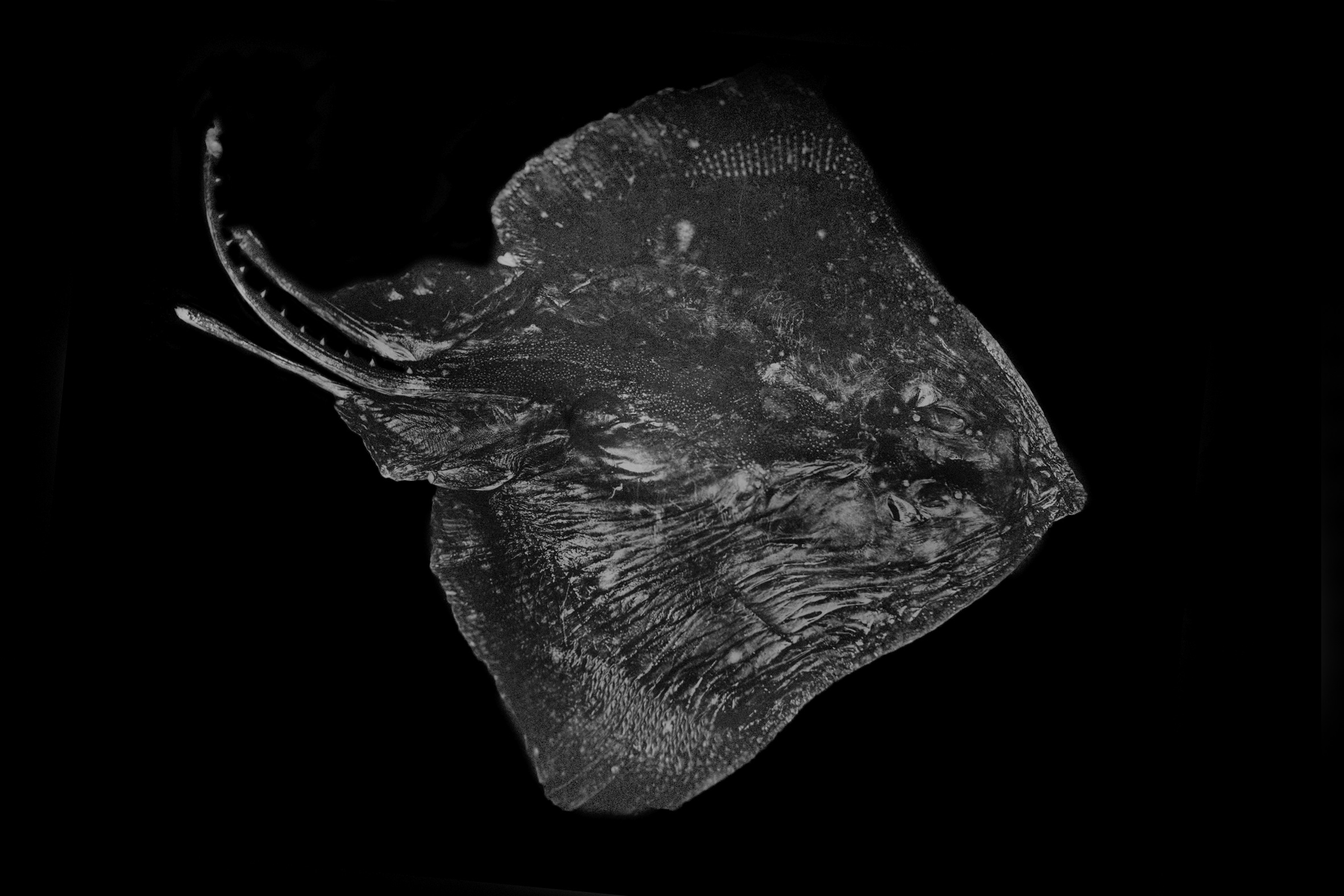

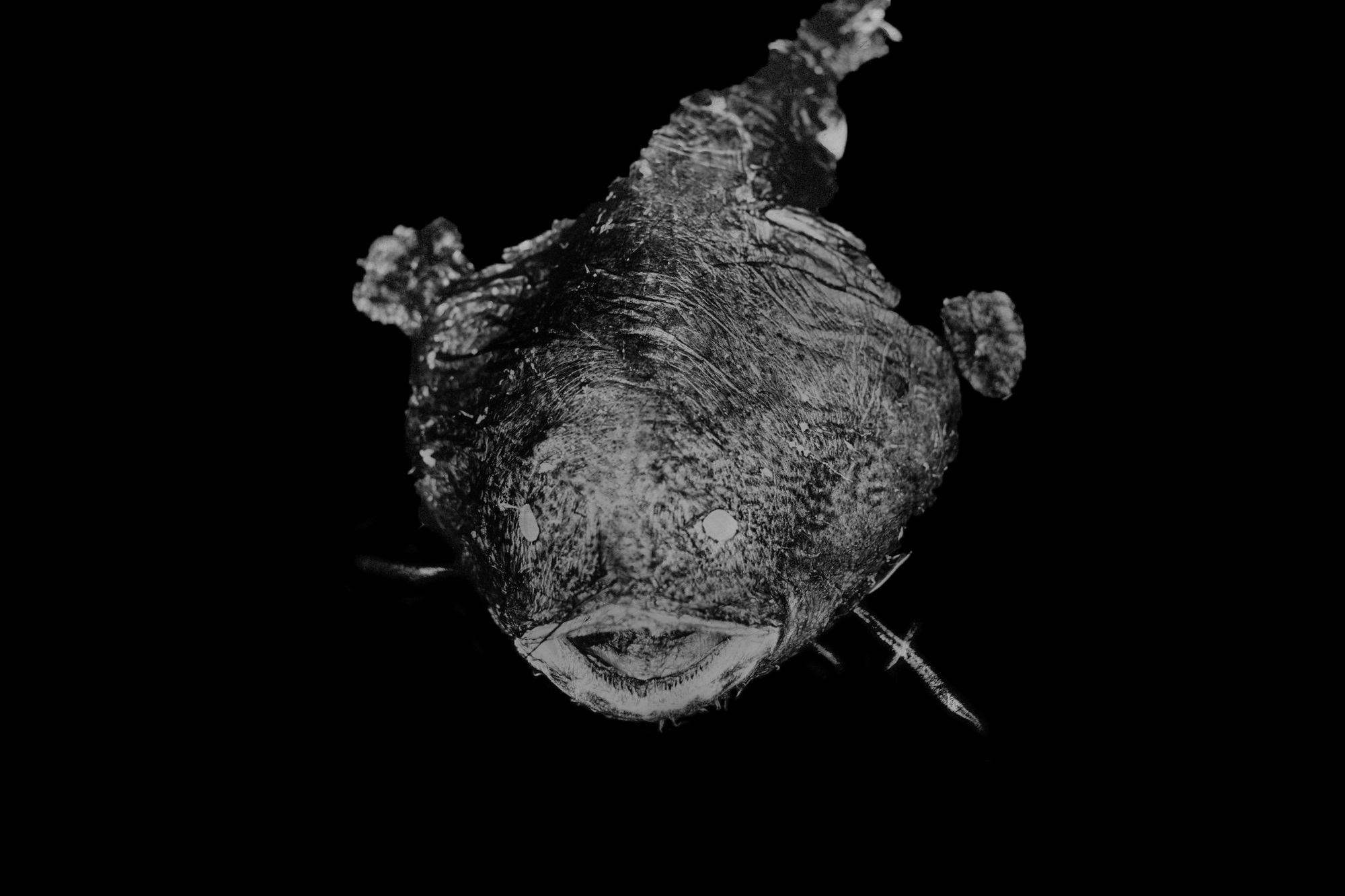

While an artist in residence at our fish collection, photographer Phillip England used an antique technique to look at our collection in a new way, creating black and white tintype portraits of fish specimens. Phillip uses the collodion tintype process, which dates from the 1850s.

“There’s nothing quite like a tintype photograph,” Phillip said. “At the fish collection, the specimens seemed to come to life again in their tintype portraits. The uniqueness of each tintype symbolises the uniqueness of each fish in the collection.”

Phillip selected fish specimens to photograph from among our many jars, drums and tanks of fishes. Each specimen was taken out of storage for around ten minutes, dried slightly, photographed and then returned to ethanol storage while the photographic plate was being developed.

The collodion tintype process uses a silver-based photographic emulsion poured onto a metal plate. The plate is exposed for a minute or two inside a large format bellows camera made of wood and leather, with a glass lens. The plate is then developed and fixed and the small, one-of-a-kind image is complete within minutes. This led to tintypes becoming popular in the mid-19th century for studio portraits and at fairs.

Phillip’s exhibition Denizens, an unusual visual perspective on the fascinating and scientifically important specimens in our Australian National Fish Collection, runs at Salamanca Arts Centre in Hobart until 20 February 2018.

Add this to your collection

Did you know The Australian National Insect Collection holds 12 million specimens?