By Kim Pullen – Australian National Insect Collection

Insects hide their enormous diversity well. We may hear that several thousand species live in and around our town or city, but where are they all?

They are in every patch of garden or vegetation. They are on nearly every bird or mammal that walks, runs or flies around us (think lice and ticks for example).

We don’t see a lot of them because most are small, some minute, and live hidden from our view. And if they are a rare species as well, then even entomologists (scientists that study insects) don’t get to see them much. The twisted-wing fly, which is actually not really a fly at all, is one such insect.

Underside of the head of a male twisted-wing fly, showing the complex branched antennae and peculiar berry-like eyes. Captured by scanning electron micrograph (SEM) by K. Pickerd, from ‘The insects of Australia’, 2nd ed, CSIRO 1991.

Strepsiptera is the taxonomic group these enigmatic creatures belong to, so we can also call them strepsipterans. That name is from the Greek, streptos meaning twisted, and pteron meaning wing. But these features really only refer to the males, which, unlike the females, also have legs, eyes and antennae like most adult insects.

The male lives only a matter of hours and if there’s one thing on his mind during his short life it is sex—his only goal is to find a female and mate.

The female is a maggot-like parasite that never emerges from her insect host— in most cases a wasp, bee or plant hopper. The only time she sees the light of day is when she pokes her fused head and thorax out from between the host’s body segments to emit a powerful pheromone. Wafting along on the breeze, the molecules are picked up by masses of sensory pits on the male’s complex antennae, and he responds by flying towards the source.

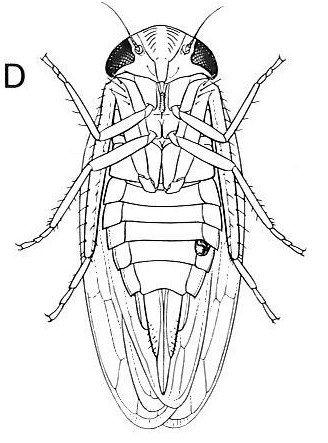

A leafhopper turned upside-down. A female twisted-wing parasite is in its abdomen, with its head visible between the segments on one side. Drawn by M. Quick, from ‘The insects of Australia’, 2nd ed, CSIRO 1991.

Here the story starts to get bizarre…

The female has no external genitalia as such. What she does have is a brood canal that opens near the front of the body. In a terrifyingly named process called hypodermic insemination, the male injects sperm into this canal and it passes directly into her circulatory system to fertilise eggs drifting there. The resulting minute offspring—and there are many thousands of them—make their way out of their mother’s body through the brood canal as very active larvae. They can spring through the air, and seek out a host to parasitise. Most will die before finding one, but the lucky ones that do will latch on to that host, penetrate its skin and then, having no further need for mobility, will transform into a second-stage larva without legs.

The twisted-wing fly larva is now an internal parasite, and will remain inside its host until maturity. If it is a female, she will never leave and only show her face to the world momentarily. If it is a male, it will leave its host for an anxious few hours riding the breeze with one thing on its mind.

1st February 2013 at 1:00 pm

Reblogged this on Diadasia.