Can you have social media accounts and be safe online?

Our species has undergone a significant shift in the way community is realised. Facebook has 2.2 billion users – about 90 times greater than the population of Australia. 25 per cent of humans use the site at least once a month. It’s quite likely that you’re reading this on a browser that’s also logged into your Facebook account – you may have even found a link to this page through Facebook.

With the recent revelation that Facebook’s third-party application settings once allowed for large-scale transfer of user’s (and friends-of-user’s) profile data, and one particular instance of that data being passed to now-infamous political marketing firm Cambridge Analytica, the core of our relationship with social media feels different and conflicted.

Since the revelation, a #DeleteFacebook movement was trending across a few social media sites, but the story isn’t quite as simple for the majority of users, who rely heavily on social networking.

At our Data61 unit, we focus on deep science and deep tech, alongside exploring the cultural, social and economic risks and benefits of technology. Part of our mission is furthering the interests of Australian community, and privacy is a major factor in much of the work we do. The quantities of information transferred between previously disconnected individuals and groups is expanding both in quantity and diversity.

Dali Kafaar, Group Leader of Data61’s Information Security and Privacy Group and Scientific Director of the Optus-Macquarie University Cyber Security Hub, has published a range of research on the complex relationship between the data we generate as users and the lifecycle of that data after it leaves our hands.

We spoke to Dali Kafaar about what the recent news means for your own social media use:

D61: A lot of us have been using Facebook for almost a decade now. Why is that trove of information we’ve loaded onto their servers something we should think about?

DK: People who use social media platforms submit ‘explicit’ data to platforms, for example, consciously liking the fan page for a particular band. En masse, and over time, these explicit data points can be used, through inference to create an implicit data set: eg, inferring that for everyone who ‘liked’ a band might also possess a particular personality trait.

D61: That’s surprising. Has this been studied?

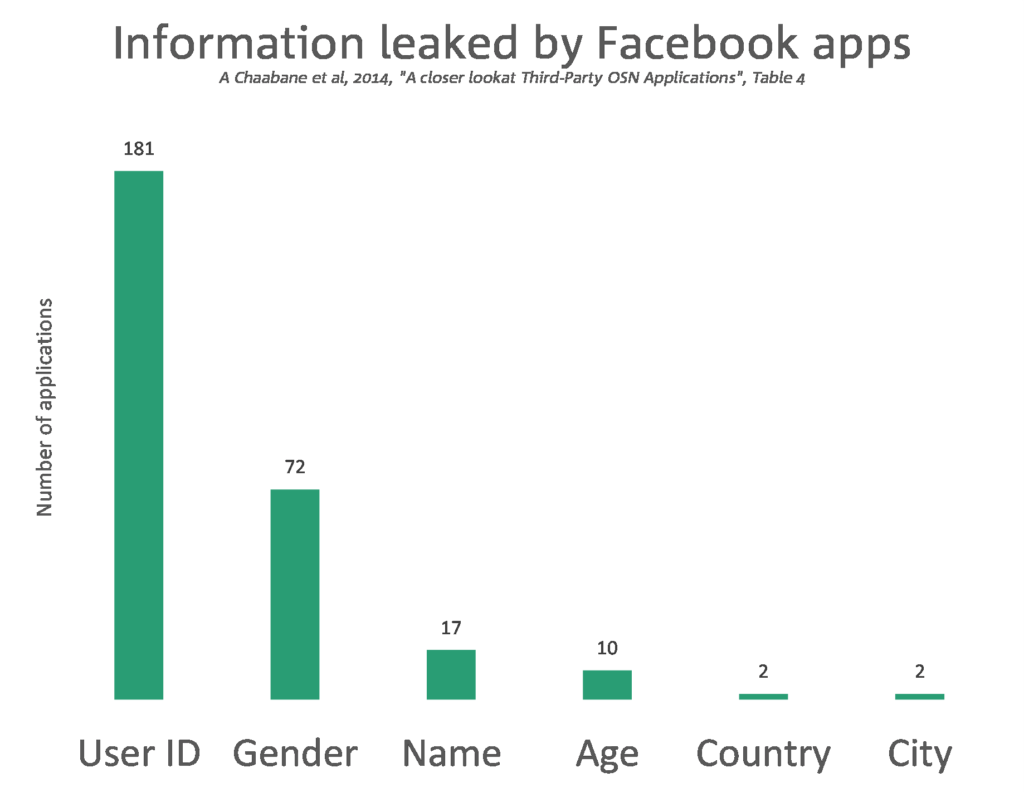

DK: A paper we published in 2014, examining 997 Facebook and 377 ReRen (a chinese social networking site), found that 22 per cent of Facebook apps provide user’s information to one or more fourth-party tracking entities, such as advertisers, entertainment companies or analytics firms.

In 2012, we published a paper entitled ‘You are what you like: Information leakage through user’s interest”, where we guided a small group of volunteers, who made their Facebook information available to us, through what they were really saying when they ‘liked’ pages. Specifically, we used their music-related Facebook likes to infer surprisingly accurate private information.

D61: That’s pretty similar to the recent news – seemingly innocuous information can be converted to deeply private insights. Does this mean we should stop using Facebook?

DK: Our model could predict hidden information, which suggests these sites need to raise the bar of privacy protections. For now, social media is really great in many different ways, but people should be cautious in how they use it. You should keep, in the back of your mind, that a lot can be inferred from the small things you’re doing.

D61: Do you use Facebook?

DK: I do use Facebook, but I don’t use it that often. I visit Facebook once a week, but I also don’t provide too much information. I pay attention to things that might be perceived as seemingly harmless information – our ‘likes’ are a particularly powerful signal that can be used to draw private inferences about us.

D61: This isn’t just Facebook, is it? Don’t most sites track user behaviour as they move across sites?

DK: Yes, you could potentially install anti-tracking tools in your browser. This is something else we’re examining directly, and we’re working on a new tool that counteracts tracking across sites. We presented on blocking JavaScript tracking at least year’s Privacy Enhacing Technologies Symposium. We’ve done work on ‘Virtual Private Network’ apps too, which purport to protect your privacy but can come with risks of their own.

D61: What about after the data’s left our hands? How can companies, business and governments stop sensitive data sets getting in the wrong hands?

DK: We work on technology that can algorithmically remove identifiable individual information from data sets while at the same time preserving the ‘statistical shape’ of the original data. The underlying philosophy of this approach is ensuring that we don’t have to opt-out of important and increasingly unavoidable digital tools if we want to be confident about our privacy.

Though there’s plenty of work being done to increase awareness of the very novel risks presented by big new digital platforms, and to protect large troves of sensitive data collected by companies, there’s always real worth in being wary of what you’re signing up to when you sign up for useful and slightly addictive tools like Facebook – we’ve learnt, this month, that there’s a decent chance your data might come back to bite, if you don’t.

D61: So, should I delete Facebook?

Dali: This depends on how much you get out of using Facebook, and how strongly you want your information to remain truly private. The key issue here isn’t deleting or not deleting Facebook; it’s really that many of us are unaware of just how ‘leaky’ these networks are, and so we end up with a false sense of security. One way of correcting that is simply to provide less information to a social media site, and to make more thoughtful decisions about the information we do provide even when these are seemingly harmless.

16th February 2019 at 4:52 pm

I couldn’t agree with you more.

16th February 2019 at 4:50 pm

I’m not really under any delusions about the security of the data I’m freely giving away. My concern is more around who is buying the data. Is it only companies wanting to sell me sneakers and power tools? Is it the government? Foreign government? Special interest political groups?