Small heroes with a big impact. Plankton are an important indicator of the health of our oceans. Today, the first ever Australian plankton report has been released, describing the state of our oceans through the eyes of these tiny drifters.

Nyctiphanes australis, a type of krill

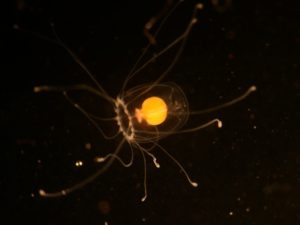

Big eyed and beautiful, the Nyctiphanes australis (a type of krill)

Imagine floating in the wide open ocean, drifting with the currents as they carry you across the vast and deep blue sea. Sound like fun?

This is what life is like for the trillions of plankton that inhabit our seas and provide the foundation of the marine food web that supports life in our oceans. Oh, and they just happen to produce about half of the oxygen we breathe too!

Plankton are an important indicator of the health of our oceans. Today, the first ever Australian plankton report has been released, describing the state of our oceans through the eyes of plankton (well some of them have eyes…).

Plankton 2015 is based on plankton data from the Australian Integrated Marine Observing System (IMOS) and looks at why plankton are important to the health of our oceans and Australia’s future prosperity.

- The intricate details of a copepod.

- The beautiful Turritopsis lata – Copyright L. Gershwin

- Feathery appendages on the copepods stop them from sinking.

- Keesingia Gigas, a new species of Irukandji (box jellyfish) described in 2014. Their sting can severely harm (and potentially kill) people. Credit: John Totterdell MIRG Australia

- Comb jellies in their own phyum.These jellyfish can be invasive and have taken over the Black Sea in the past.

- Subeucalanus crassus

- Not all plankton are small. Here is a colonial tunicate (in our phylum so related to us!) and can be up to 20m long. Credit: Karen Gowlett Holmes

Plankton Facts

- The word plankton comes from the Greek planktos meaning ‘to drift’, and although many of the phytoplankton move and zooplankton can swim, none can progress against the currents.

- The most common species of plankton, a zooplankton called copepods, are the most abundant animals on Earth.

- But not all plankton are microscopic. Jellyfish are plankton too, and like their smaller cousins they too cannot swim against the tide.

The plot thickens

The amount, growth and composition of plankton is critical to the carrying capacity of the world’s oceans. That is, how much plankton there is, and where it is, determines how many fish, marine mammals and turtles are in the sea.

Plankton also impacts human health. Some species produce toxins and form large potentially fatal algal blooms and some species, like the Irukandji and box jellyfish, are venomous.

Not content with just affecting humans in a localised area, plankton can also influence the pace and extent of climate change. Through photosynthesis, plankton can suck carbon from the atmosphere and fix it in the deep ocean for thousands to millions of years, a process known as the ‘biological pump’. It has contributed to the ocean sucking up 40% of the carbon dioxide people have produced – it would be a much warmer world without plankton.

That’s not all. The last time you filled up the car, you might have been pumping dead zooplankton into the tank. Zooplankton bodies that settled on the sea floor over millions of years has formed the oil we now burn.

Sensitive little suckers

Plankton is sensitive to changes in temperature, acidity and nutrients. The fact that plankton is abundant, short-lived, and not harvested by people means they can tell us about the changing climate, the state of global fisheries, and about ecosystem health and biodiversity.

Through the IMOS Australian Continuous Plankton Recorder (AusCPR) survey and the National Reference Stations (NRS) program, researchers are collecting and counting thousands of plankton samples, as a window into the health of our oceans.

A sea change

Our oceans are changing and plankton can show us how. Warming Australian ocean temperatures have altered the distribution of many plankton species. Researchers have found that on the east coast of Australia, plankton have moved southward by 300 km over the past 30 years.

Glowing plankton disturbed on beach.

The glow of plankton when disturbed is not only striking, but an important defence mechanism against predators. Credit: L. Gershwin

Off Tasmania’s east coast at Maria Island, there has been a shift from cold-water to warm-water species. This is consistent with what is happening in other ecosystems under global warming and is likely to have repercussions up the food chain. Warm-water plankton is smaller and, like some snobby people, some fish, seabirds and marine mammals just don’t like the taste.

With warming water, the red tide species Noctiluca scintillans, once only found around Sydney, is expanding throughout Australian waters and into the Southern Ocean, where it has never before been observed. This species can cause problems for aquaculture farms.

In various parts of the world that have been heavily fished or polluted, jellyfish – which are the largest plankton – have bloomed in massive numbers. The good news is there is no evidence that jellyfish abundance has increased in Australian waters.

A knowledge bloom

Plankton allow us to listen to the ocean’s heartbeat. Plankton data are being used in regional and global assessments of ecosystem health. Australia, through IMOS, is contributing to this collection, in particular within or near areas of high conservation value, including protected areas such as the Great Barrier Reef. Information from Plankton2015 will be used in the next Australian State of the Environment report to highlight how our marine estate is changing. As more data is collected, our knowledge on the baseline conditions across Australia will improve.

Find out more about how we are sustaining Australian fisheries.

10th April 2017 at 7:22 pm

You say that krill are a significant plankton species. I worry that the latest western world fad of taking krill oil as a dietary supplement is just as thoughtless as killing whales for oil. From where are all these tons of krill coming? What is the effect on plankton populations? Is the nutrient value of the krill pill for humans so important to us that we are blindly robbing the plankton body of a key source of basal level nutrients for other ocean species?

Pingback: Lynchpin – The Ocean Project – Art Science Collaboration | PLANKTON – learn more