Penny Whetton, right, addressing a March for Science rally. Her death last month shocked and saddened colleagues. Supplied by family

Last month we lost Dr Penny Whetton – one of the world’s most respected climate scientists and a brilliant mentor to the next generation of researchers. Penny will also be remembered as a passionate environmentalist, artist, photographer and champion of the transgender community.

Penny was at the forefront of climate change projection science for more than three decades. She played a key role in putting CSIRO, and Australia, on the map as a world-leading centre for climate change research. Her groundbreaking scientific work was among the first to raise awareness of the challenges of a warming world, laying the groundwork for possible solutions.

Penny was a strong believer in the power of each person to make a difference, at work and elsewhere. Her professional career is a great example. She also encouraged those around her to seek out challenges that could benefit the world. That creative energy continues to flow through everybody who was close to her.

Penny Whetton at Cradle Mountain in Tasmania. She was known as a passionate environmentalist. Supplied by family

A global climate science pioneer

Penny’s work focused on understanding the emergent threat of a changing climate on Australia and the region. She authored papers and reports that have become fundamental to our understanding of how climate change would affect us.

Penny was recruited to the CSIRO’s new climate impacts group in 1990, after completing a doctorate at the University of Melbourne. She rapidly established a reputation for high quality science and innovative thinking.

Penny was a senior leader for much of her career and managed many large collaborative projects with colleagues in CSIRO and the Bureau of Meteorology. After retiring in 2014, Penny became an honorary research fellow at CSIRO and the University of Melbourne, where she continued to be involved in climate research, advisory panels and consulting work.

Over her 25 years at CSIRO, Penny drove innovation in making climate projections useful to decision makers. Her clear grasp of the science and its impact led to novel ways of communicating many complicated concepts.

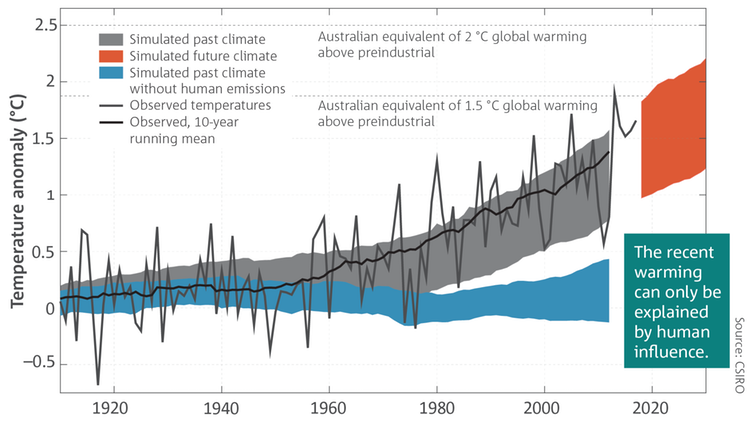

One of Penny’s many great ideas was to combine historic climate observations with future projections in a single timeline of data – creating a seamless path from past to future. This visualisation method is now a standard part of the climate projections toolkit.

Penny led the development of national climate change projections for Australia in 1992, 1996, 2001, 2007 and 2015. The 2015 projections remain the most comprehensive ever developed for Australia. They are widely used by the private sector, governments and NGOs and were one of Penny’s proudest achievements.

This style of representing the climate as a seamless path from past to future was one of Penny’s many great ideas. State of the Climate 2018

Penny’s science was renowned internationally as well as at home. She spoke at dozens of international conferences, and workshops and journalists sought her out regularly for interviews.

She was a lead author for three climate change assessments by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the world’s leading authority on the subject. Penny’s work was recognised many times, including with a Eureka Prize in 2003 and internationally as part of the IPCC team that won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007.

More recently, Penny provided scientific assurance on the external advisory board for the European Climate Prediction system, a project strongly influenced by methods and thinking developed under her leadership in climate projections for Australia.

Penny Whetton taking part in a panel discussion at a CSIRO open day in Melbourne. Supplied by David Karoly.

Generous collaborator and mentor

Penny was instrumental in forging links between researchers in CSIRO, the Bureau of Meteorology and universities. This led to several collaborative, high-impact reports on climate change projections.

Penny was generous with her time and guidance – committed to developing the next generation of climate change specialists. Always with a smile on her face, she combined a great intellect and strongly held opinions with a receptiveness to the ideas of others.

Many of us writing this were mentored by Penny at various stages in our academic careers. Anyone who’s studied for a Masters or PhD knows meetings with academic supervisors can be stressful. But meetings with Penny were quite the opposite – she was friendly, but academically rigorous. Collectively we owe her an immense debt of gratitude.

Penny’s diverse knowledge and skills – including geology, geography, meteorology, climate, history, carpentry, painting and photography – gave her unique perspectives to draw on when tackling the wicked problems posed by climate change.

A painting completed by Penny Whetton in March 2018 titled ‘Liffey River downstream from the falls’. Acrylic on canvas. Supplied by family

Penny made our lives richer

Penny was a real friend to many. Students became colleagues, colleagues became friends, and all of us were invited to be part of her life in a diverse extended family. We were pleased to support Penny in her own gender affirmation, and for many LGBTIQA+ scientists, Penny was both role model and supportive friend.

Penny had a wonderful knack for making inclusive conversation, whether at work or over dinner. Her contributions were insightful and grounded in truth, very often tinged with humour, and always kind and understanding.

We all assumed there would always be another dinner, and another opportunity to enjoy her company and be fascinated by her conversation. Sadly, and shockingly, this possibility has been taken from us.

Penny made our lives richer, more interesting and more human. Her absence leaves a massive hole in our community and our lives.

Penny Whetton is survived by her wife Janet and adult children John and Leon.

Vale Dr Penny Whetton, 1958-2019. Supplied by authors

The following people contributed significantly to this article:

Aurel Moise (Bureau of Meteorology), Barrie Pittock (retired), Chris Gerbing (CSIRO), Craig Heady (CSIRO), David Karoly (CSIRO), Debbie Abbs (retired), Dewi Kirono (CSIRO), Diana Pittock (retired), Helen Cleugh (CSIRO), Ian Macadam (University of New South Wales Sydney), Ian Watterson (CSIRO), Jim Salinger (University of Florence, Italy), Jonas Bhend (MeteoSwiss, Switzerland), Karl Braganza (Bureau of Meteorology), Kathy McInnes (CSIRO), Kevin Hennessy (CSIRO), Leanne Webb (CSIRO), Louise Wilson (Bureau of Meteorology), Mandy Hopkins (CSIRO), Marie Ekström (Cardiff University, UK), Michael Grose (CSIRO), Rob Colman (Bureau of Meteorology) and Scott Power (Bureau of Meteorology).![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.