The Square Kilometre Array, or SKA, is a next-generation radio telescope that will be vastly more sensitive than the best present-day instruments. It will give astronomers remarkable insights into the formation of the early Universe, including the emergence of the first stars, galaxies and other structures. We caught up with research engineer Mia Baquiran to find out more about this amazing new instrument and her role in getting it off the ground and into the skies.

When they flick the switch on the world’s largest telescope, one woman’s work will come to life.

If it takes a village to raise a child, it takes a planet – or at least ten countries – to build the the world’s largest radio telescope, the Square Kilometre Array.

The Square Kilometre Array, or SKA, is a next-generation radio telescope that will be vastly more sensitive than the best present-day instruments. It will give astronomers remarkable insights into the formation of the early Universe, including the emergence of the first stars, galaxies and other structures.

Consisting of thousands of antennas linked together by high bandwidth optical fibre, the SKA will require new technologies and progress in fundamental engineering. The telescope’s design and development is being led by the international SKA Organisation.

Radio telescopes add to observations made by optical and other telescopes by revealing different information about stars, galaxies and gas clouds. Because radio waves can pass through clouds of dust and gas, radio telescopes are able to observe objects and processes not visible to other telescopes.

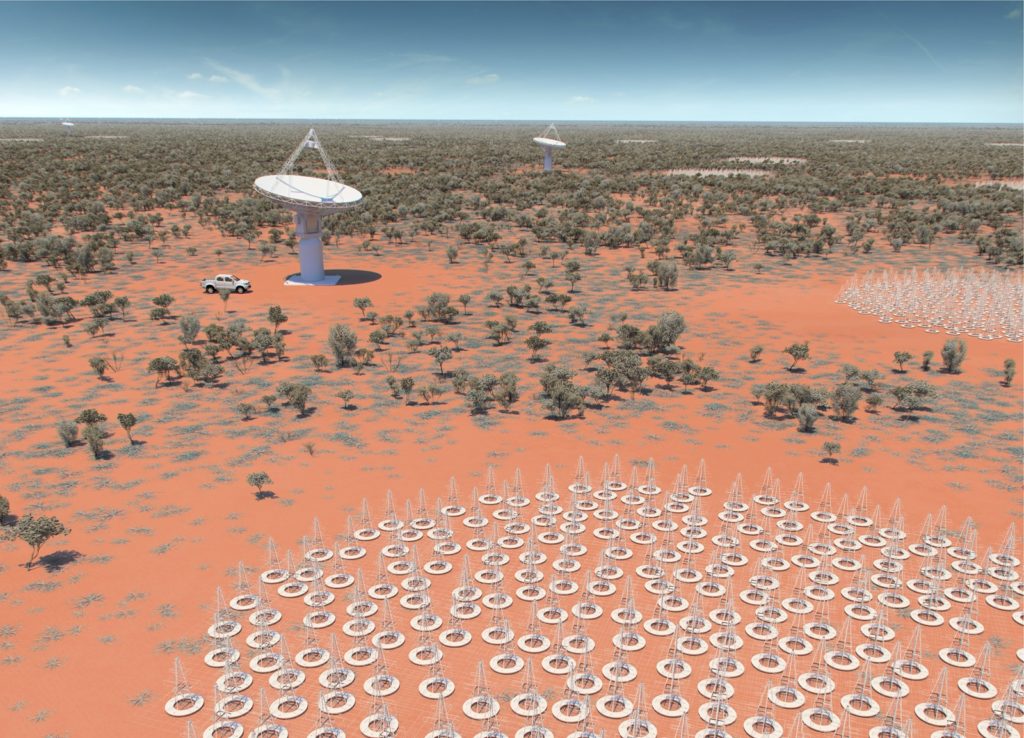

An artist’s impression of the Square Kilometre Array’s antennas in Australia. ©SKA Organisation. We acknowledge the Wajarri Yamaji people as the Traditional Owners of the Murchison Radio-astronomy Observatory site.

Construction is due to start in 2018 and around the globe 11 groups, all with members from several countries, are working feverishly on different aspects of the project to make it come together.

Australia has a presence in several of these groups, and indeed leads two of them. Our very own Mia Baquiran is one of the researchers working on this exciting project.

She spends her days in a quiet, ground-floor office in a leafy suburb of Sydney, working on systems that will go into the international SKA radio telescope.

Mia’s role in this ‘moon-shot’ project concerns a telescope called ‘SKA Low’, an assembly of more than a hundred thousand low-frequency antennas that will be housed at CSIRO’s Murchison Radio-astronomy Observatory in Western Australia.

SKA Low has no moving parts but it is still a complex beast. The signals from the antennas have to be brought together and compared with each other (‘correlated’) to create a view of the sky.

Mia is working on the system (the correlator and beamformer) that does this. She writes ‘permanent’ software (firmware) for controlling the subsystems of the correlator and beamformer.

Our research engineer Mia Baquiran is working on the software that will create a view of the sky using the SKA Low radio telescope.

So how did she get into this space you might ask?

“When I was thinking about what I wanted to do at university I didn’t have that much direction,” Mia said. “Really the only thing that got me excited was the concept of engineering, being able to develop things and understanding how things work.”

She was always interested in physics and robotics appealed too, so she headed for a degree in mechatronics, a field that brings together mechanical engineering, electronics and software.

After finishing her studies at UNSW in 2012 she worked at a small software company, then joined our astronomy and space science research area.

Mia loves problem solving. “There’s always that wonderful moment when you finally find a solution,” she said.

She’s also curiosity-driven. “I like the idea that I can learn something new every day,” she said. “Engineering is constantly changing, so you have to become a lifelong learner.”

“I do enjoy the opportunity to learn from people who are more experienced than me, and that’s definitely well-facilitated in CSIRO.”

Because the correlator and beamformer project is international Mia has had the opportunity to visit the Netherlands to work with colleagues there.

The SKA will give radio astronomers a view of the past a million years after the Big Bang, when the universe first evolved to what is referred to as the “cosmic dawn”.

But what’s in store for Mia in her future?

“I’d like to continue in electronics and FPGA (field programmable gate array) design,” she said.

“Ideally I’d like to continue in radio astronomy, because we’re in a special position being in Australia, where it’s one of the fields that we’re world leaders in.”

Find out more about how CSIRO is helping to bring the Square Kilometre Array to life.

4th May 2017 at 8:32 pm

Very interesting article! As an IT professional, Mia’s job is the kind of work I would have loved to do rather than the commercial & business applications I had continuously done in the last 40 years.

Kudos to Mia’s curiosity and diligence and her yearning to create and discover. I’m excited and can’t wait!!

Keep it up!!

14th March 2017 at 9:52 am

I really loved working on things like this! There’s a lot of free and open source software if anyone wants to get back into hardware development.

13th March 2017 at 10:49 am

Lost me with a BS caption “working on software” when that’s a printed circuit layout on the middle monitor and a schematic on the left. Nothing to do with firmware. When will PR spin doctors learn that accuracy counts? And BTW, you don’t normally touch type on PCB layouts, you use the mouse.

13th March 2017 at 11:52 am

Hi David,

Like the first image/caption, the caption you’re referring to is a stand-alone sentence related to Mia’s work, not to the image/scene itself.

Regards,

Jesse

14th March 2017 at 11:51 pm

A caption that’s unrelated to the picture it, ehr, captions? Sounds like something out of the White House.

Guys, it’s a really nice story. I love the SKA and seeing bright young people working on it. But inaccuracies introduced by the PR department can be damaging. Maybe not in this case, but where do you draw the line between acceptable and unacceptable inaccuracies? When will an inaccuracy give a gainsayer ammunition? I bet if you had gone back to Ms Baquiran she would have corrected you. I expect she does hardware /and/ software, so the caption could have been:

“Our research engineer Mia Baquiran is working on the hardware and software that will create a view of the sky using the SKA Low radio telescope.”

13th March 2017 at 4:33 pm

Mr. Stonier-Gibson,

Such an obnoxious comment of yours. Way to pick at a minor detail you misinterpreted rather than enjoying the main story.

Regards,

David

14th March 2017 at 11:39 pm

David, I have a strong dislike of inaccuracies in technical reporting. It is akin to the ignorance of technology and science shown by politicians or climate change denialists. Technical/science reporting should be impeccably accurate, just as science itself should be rigorous. How can our children, or politicians, understand the truth if they get confused by confusing reporting?

17th March 2017 at 3:34 pm

David Gedymin I have to agree with David Stonier-Gibson. While it is a minor point, it gives the detractors of science an excuse to attack the rest of the article. In the current climate with some significant anti science advocates in government, in Australia, the US and elsewhere in the world we have to be exceedingly vigilant about anything which can detract from the value of the science. As a CSIRO scientist myself in the past, I always cringed whenever science was reported with obvious inaccuracies and inconsistencies. It is bad enough when it appears in the general press, but when it appears in a CSIRO publication/blog it can have a cumulative damaging effect on credibility.

That said otherwise the artile was great and the work being done is fantastic!

10th March 2017 at 5:49 pm

Brilliant.

Fabulous.

Can’t wait.

#skaNOVEL

Indeed – I’m so excited that I wrote a drama novel “A Trojan Affair – The SKA at Carnarvon”… and the SKA organization love it. The Department of Science have already bought 300 books they distribute to give people insight into the project.