By Carrie Bengston

You might not realise, but we use maths in nearly all of our daily activities. Every time we check the weather, use the internet or travel anywhere, maths plays a part. On a larger scale, maths can even be used to protect our flora and fauna from invasive pests. Our Biosecurity Flagship Director Dr Gary Fitt explains.

Zoos are a great place to visit but we don’t want Australia to become one. Image: Shutterstock.

Q: You’ve said we don’t want Australia to become a zoo. What do you mean?

A: Zoos have collections of animals from all around the world. While they’re fun to visit, we don’t want Australia to become one. Australia already has its own magnificent native flora and fauna. We’re an island continent and our wildlife really is unique in the world.

Take the Gouldian Finch for example. I’ve just spent a week in the Kimberley region of WA observing and counting these spectacularly colourful little birds. These endangered species are found nowhere else in the world but northern Australia. It would be tragic if they were lost from nature because of the introduction of a pest or disease.

With the world so connected by air and sea, the risks are real that Australia could become a zoo of introduced species alongside a reduced set of native ones.

It’s not just animals either – our plants are unique too. Botany Bay, where Captain James Cook landed, is named after the science of plants because so many unusual plant specimens were collected there by Joseph Banks. Unfortunately, our bushland today can become a new home for invasive plants, like the garden escapees lantana and privet.

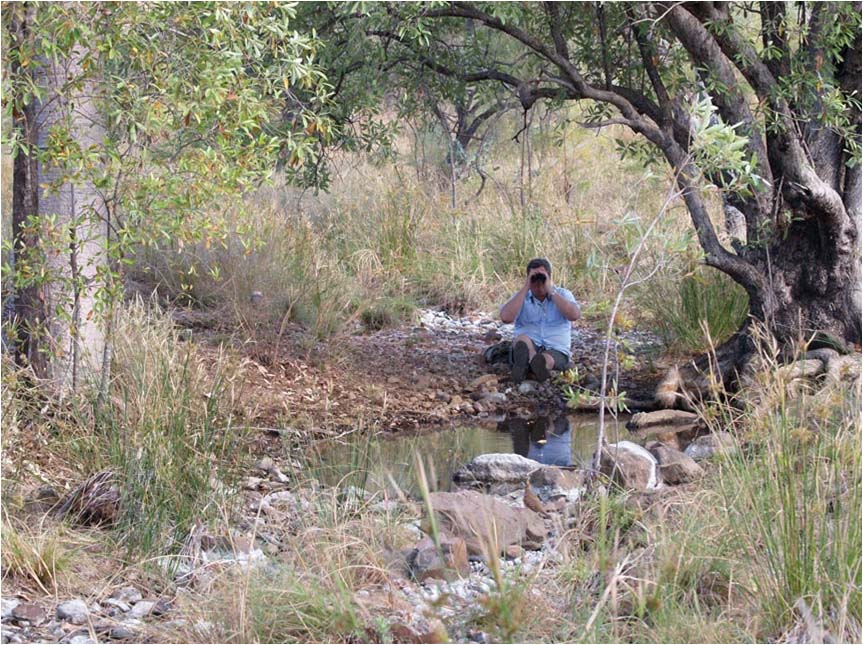

Australia is home to some of the world’s most unique and precious wildlife, just like the Gouldian Finch. Image: Cheryl Mares.

We don’t want invasive animals, plants or even micro-organisms from other parts of the world coming in and getting a foothold. Australia’s ecosystems would change forever, affecting health and agriculture. We need to protect our own biodiversity as much as we can. Our biosecurity research is key to that. It’s in our interests and future generations’ interests to get that right.

Q: You’ve enlisted mathematicians and statisticians to work on this research. What do they bring to the field of biosecurity?

Biosecurity is in a sense a game of probabilities. In this game the mathematical sciences are critical in two ways.

The first is to do with risk. Maths can help us determine the chances of a particular pest arriving and surviving in Australian environments, often in the face of uncertainties. By better understanding the risks and pathways, we can optimise investments in the right kind of surveillance systems. For instance, some of our projects quantify the riskiest pathways of entry in Australia, while others look at where to focus surveillance in ports.

The second is to do with response. Once a pest has arrived here, how do we get rid of it or limit its spread? We need to choose strategies that have the greatest chance of success. Once implemented, we need to know whether those methods are working.

Maths and stats play a vital role in protecting Australia from invasive pests. Image: Cheryl Mares.

By making decisions based on statistical inference from the available data, rather than gut feel or vested interests, we can help policy makers and operational Biosecurity players better target funds for response. Maths is also important for modelling the life cycle stages of invasive species which might be most vulnerable to biological control.

Q: It’s Canberra’s centenary year. How has research in Canberra contributed to our understanding of bioinvasion and biosecurity?

A: Canberra is and has been home to some of Australia’s most famous research into invasive pests.

Canberra was where the ANU’s Frank Fenner worked on myxamatosis with CSIRO’s Ian Clunies-Ross and Macfarlane-Burnett. Mid-last century, they famously injected themselves with the myxoma virus, brought in to control the country’s rabbit plague, to prove it wouldn’t infect humans.

For years, we’ve been helping to control ‘those pesky wabbits’.

The introduction of myxamotosis was a big step forward in controlling a pest that had devastated huge areas of farmland and was costing millions in lost production. We’re continuing our work here to improve the effectiveness of the next generation rabbit biocontrol agent, calicivirus.

***

September 12 – 13 is the Biosecurity and Bioinvasion workshop in Canberra. Our experts are discussing how maths is essential in protecting Australia from the threat of pests and diseases as part of the International Year of the Maths of Planet Earth.