Our new roadmap outlines the opportunities for hydrogen in commercial aviation.

Imagine planning a trip where you could be confident your flight was environmentally friendly. It’s the dream.

Well, carbon-free air travel might be closer than you think. Our recent report with Boeing looks at how we can decarbonise the commercial aviation industry. And the answer could be in hydrogen.

Planes, trains and automobiles

The transport sector is a major emitter of greenhouse gases. Global transport emissions make up around a quarter of all emissions. And the aviation sector makes up a big slice of that pie. The global aviation industry consumes over three times more energy than the whole of Australia each year!

That’s not to say that the aviation sector isn’t working hard to reduce its environmental impact. There are strict regulations in place and the commercial aviation industry has already committed to ambitious low-emissions targets. The International Aviation Transport Authority has adopted a target of a 50 per cent reduction on 2005 CO2 emission levels by 2050, with no net-emissions increases after 2020.

Decarbonising the aviation sector is also driven by community concern about emissions. But, even with these concerns, passenger demand is forecasted to increase. In fact, projections show a three-fold growth in CO2 emissions from transport by 2050. This is because increasing numbers of flights outstrips the efficiency gains in the industry.

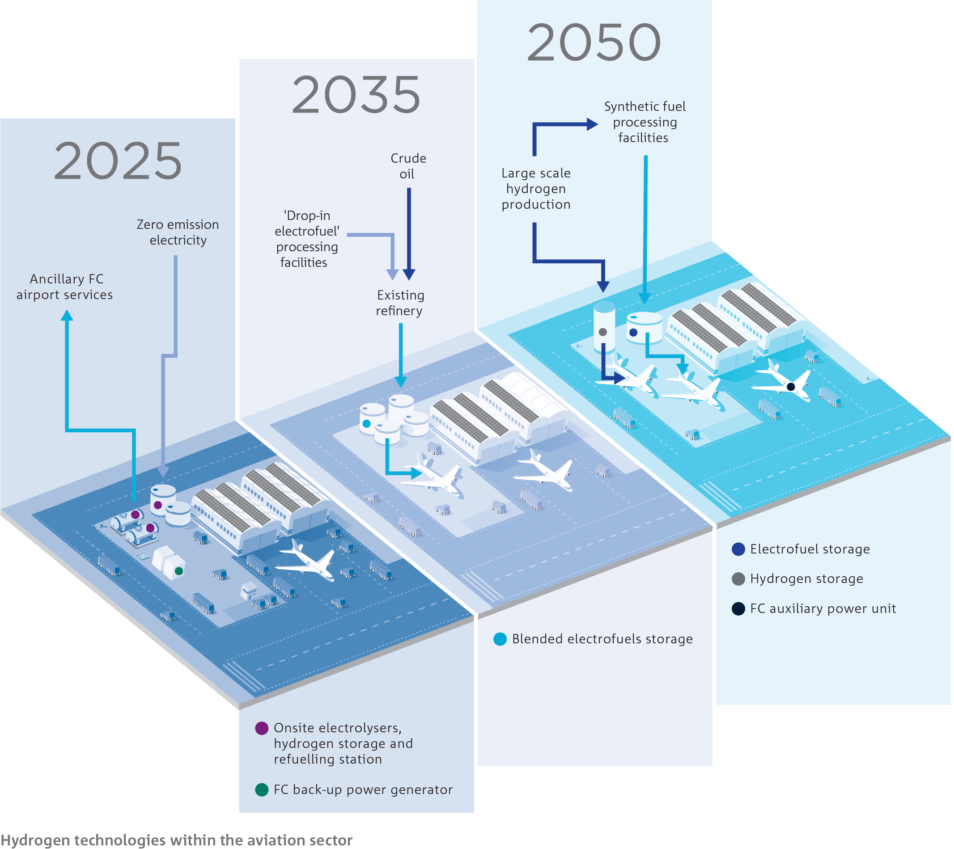

The report outlines how the commercial aviation industry can adopt hydrogen across short, medium and long-term applications.

Over time, aircraft have become more efficient and this has reduced overall sector emissions. But, to meet their targets, the sector must continue to embrace new technologies and innovation. This is particularly important for Australia as we are heavily dependent on long-haul flights to support much of our economy.

Hydrogen is already used in cars, trucks, buses and trains around the world. And hydrogen has propelled our rockets for decades! So, using it to decarbonise the aviation sector could be the logical next step. There are short, medium and long-term opportunities for the adoption of hydrogen in the aviation industry. And each has different CO2 abatement potential over time.

Short haul (between now and 2030)

In the short-term, we could upgrade ground support equipment (like forklifts and baggage loaders) by replacing what currently runs on liquid fuels to hydrogen alternatives. Ground support equipment is not a large contributor of total sector emissions. But a transition to hydrogen would save money and reduce our dependence on imported fuels. Plus, it’s a good way to start incorporating standards and operating procedures for handling hydrogen at airports.

Medium haul (from 2030 onwards)

Medium-term adoption is all about electrofuels. These are ‘drop-in’ fuels made from hydrogen and carbon dioxide, and they can be used without changing existing infrastructure. The industry needs strategic global investment for large-scale electrofuel production. But there is already a strong technology and regulatory base we can build upon. And, as in any new industry, we need to do more research and development for hydrogen to really take off.

Long haul (towards 2050 and beyond)

The long-term goal is a complete departure from conventional jet fuel and a focus on new infrastructure. And yes, that could mean hydrogen-powered planes dotting our skies. Hydrogen could play a major role in both non-propulsion and propulsion applications. But getting to that point is not without significant challenges.

One challenge is that hydrogen fuel needs more room for storage. We could solve this with revolutionary aerodynamic designs that can accommodate larger volumes of fuel. Non-propulsion applications, such as fuel cells used for aircraft taxiing, could be adopted sooner.

What does this mean for Australia?

The transition to zero-emission air travel is critical for many reasons but the big opportunity for Australia is in the fuel. We already know from the National Hydrogen Roadmap that Australia is one of the cheapest places in the world to make renewable hydrogen. And if we want to transition the world’s aircraft onto blends of electrofuels or pure hydrogen fuel, we are going to need a lot of it. Decarbonisation of the aviation industry is a big opportunity for Australia. It will help create jobs, grow our economy and establish a new industry.

Our report takes a long-term view on creating a sustainable aviation industry incorporating hydrogen. We still need further research and investment before our first jet-propulsion aircraft takes off. But efforts to achieve it are accelerating rapidly.

Air travel may be the farthest thing from our minds as the global pandemic continues. But we need to be planning for a low-emissions aviation industry that is innovative and sustainable in the long-term now. There are plenty of opportunities to introduce hydrogen into commercial aviation and it can play a critical role in decarbonising our air travel.

27th August 2020 at 3:10 am

Alternative fuel cells exist such as the hydrazine cell. This has been around for a long time and Shell’s Thornton Research centre ( now closed) made a demonstration conversion of an Austin 1300 car long ago. Coal pyrolysis, as I have pointed out elsewhere, creates a gas wit more than 50% hydrogen which can readily be separated from the materials. The other product, byproducts are in fact valuable, even th e coke can be activated to absorb carbon dioxide. I like the idea of airships and previous disasters have been shown due to faulty canvas coatings which contained a dangerous mixture of chemicals in fact used for rail welding at one time! Could airships lift an aircraft so avoiding the emission of pollutants during takeoff? A mad idea but who knows what is possible in the future!

26th August 2020 at 3:44 pm

I wish to see hybrid airships manufactured in the Hunter Valley. Hot Hydrogen lift cells; hull coated in thin film photovoltaics (Uni of Newcastle); turbo sails to make use of win for motive force; fuel cell for backup power. Financed using an issue of negative interest money. .

Please contact me if you can help.

7th August 2020 at 5:03 pm

i think fuel cells to electricity then electric maybe most efficient collect resultant water solar panel to convert it back to hydrogen and through fuel cell again for electricity

6th August 2020 at 3:20 pm

Agree. Hydrogen is driven by the fossil fuel industry. Hydrogen made by steam reforming hydrocarbons is 1/4 the cost of green hydrogen. Making and packing hydrogen consumes 60 to 80% of its embodied energy. Planes could be powered by electric motors and the electricity supplied form a metal (e.g. aluminum) air fuel cell. These cells have twice the energy density of hydrocarbon fuels. Electric motors are far less complex and quieter than gas turbines. It would be interesting to know how they compare on a power to weight ratio.

4th August 2020 at 10:41 am

Why hydrogen rather than electric? Is it the fossil fuel companies driving this? Or, when we talk about hydrogen, do we mean green hydrogen rather than blue?

What about issues of safety, stronger tanks required, issues of erosion by hydrogen, far higher cost of infrastructure etc?

How about efficiency? I understand efficiency of hydrogen is similar to that of petrol or diesel around 17-22% whereas electricity is around 69%.

Certainly there appears to be potential for hydrogen in shipping, aircraft and trucks, but it appears that for ordinary vehicles electric is becoming established as the preferable option?