Hydrogen could become a significant part of Australia’s energy landscape within the coming decade, competing with both natural gas and batteries, according to our new roadmap for the industry.

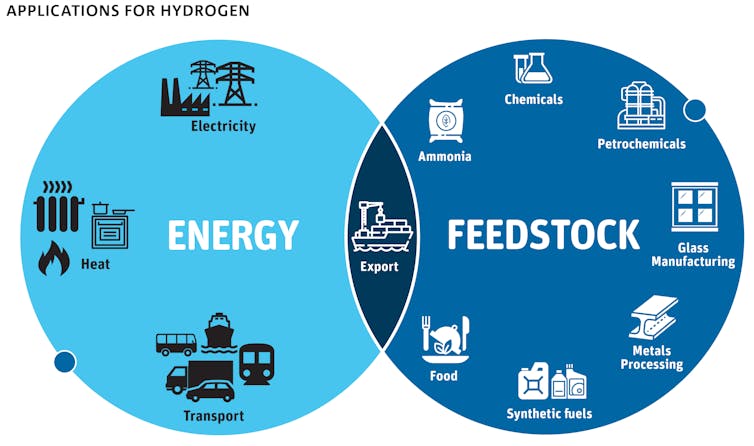

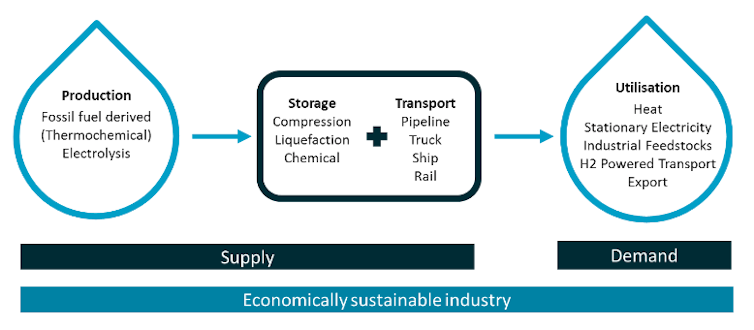

Hydrogen gas is a versatile energy carrier with a wide range of potential uses. However, hydrogen is not freely available in the atmosphere as a gas. It therefore requires an energy input and a series of technologies to produce, store and then use it.

Why would we bother? Because hydrogen has several advantages over other energy carriers, such as batteries. It is a single product that can service multiple markets and, if produced using low- or zero-emissions energy sources, it can help us significantly cut greenhouse emissions.

The benefits are potentially even greater for heavy vehicles such as buses and trucks which already carry heavy payloads, and where lengthy battery recharge times can affect the business model.

Hydrogen can also play an important role in energy storage, which will be increasingly necessary both in remote operations such as mine sites, and as part of the electricity grid to help smooth out the contribution of renewables such as wind and solar. This could work by using the excess renewable energy (when generation is high and/or demand is low) to drive hydrogen production via electrolysis of water. The hydrogen can then be stored as compressed gas and put into a fuel cell to generate electricity when needed.

Australia is heavily reliant on imported liquid fuels and does not currently have enough liquid fuel held in reserve. Moving towards hydrogen fuel could potentially alleviate this problem. Hydrogen can also be used to produce industrial chemicals such as ammonia and methanol, and is an important ingredient in petroleum refining.

Further, as hydrogen burns without greenhouse emissions, it is one of the few viable green alternatives to natural gas for generating heat.

Our roadmap predicts that the global market for hydrogen will grow in the coming decades. Among the prospective buyers of Australian hydrogen would be Japan, which is comparatively constrained in its ability to generate energy locally. Australia’s extensive natural resources, namely solar, wind, fossil fuels and available land lend favourably to the establishment of hydrogen export supply chains.

Why embrace hydrogen now?

Given its widespread use and benefit, interest in the “hydrogen economy” has peaked and troughed for the past few decades. Why might it be different this time around? While the main motivation is hydrogen’s ability to deliver low-carbon energy, there are a couple of other factors that distinguish today’s situation from previous years.

Our analysis shows that the hydrogen value chain is now underpinned by a series of mature technologies that are technically ready but not yet commercially viable. This means that the narrative around hydrogen has now shifted from one of technology development to “market activation”.

The solar panel industry provides a recent precedent for this kind of burgeoning energy industry. Large-scale solar farms are now generating attractive returns on investment, without any assistance from government. One of the main factors that enabled solar power to reach this tipping point was the increase in production economies of scale, particularly in China. Notably, China has recently emerged as a proponent for hydrogen, earmarking its use in both transport and distributed electricity generation.

But whereas solar power could feed into a market with ready-made infrastructure (the electricity grid), the case is less straightforward for hydrogen. The technologies to help produce and distribute hydrogen will need to develop in concert with the applications themselves.

A roadmap for hydrogen

In light of this, the primary objective of our National Hydrogen Roadmap is to provide a blueprint for the development of a hydrogen industry in Australia. With several activities already underway, it is designed to help industry, government and researchers decide where exactly to focus their attention and investment.

Our first step was to calculate the price points at which hydrogen can compete commercially with other technologies. We then worked backwards along the value chain to understand the key areas of investment needed for hydrogen to achieve competitiveness in each of the identified potential markets. Following this, we modelled the cumulative impact of the investment priorities that would be feasible in or around 2025.

What became evident from the report was that the opportunity for clean hydrogen to compete favourably on a cost basis with existing industrial feedstocks and energy carriers in local applications such as transport and remote area power systems is within reach. On the upstream side, some of the most material drivers of reductions in cost include the availability of cheap low emissions electricity, utilisation and size of the asset.

The development of an export industry, meanwhile, is a potential game-changer for hydrogen and the broader energy sector. While this industry is not expected to scale up until closer to 2030, this will enable the localisation of supply chains, industrialisation and even automation of technology manufacture that will contribute to significant reductions in asset capital costs. It will also enable the development of fossil-fuel-derived hydrogen with carbon capture and storage, and place downward pressure on renewable energy costs dedicated to large scale hydrogen production via electrolysis.

In light of global trends in industry, energy and transport, development of a hydrogen industry in Australia represents a real opportunity to create new growth areas in our economy. Blessed with unparalleled resources, a skilled workforce and established manufacturing base, Australia is extremely well placed to capitalise on this opportunity. But it won’t eventuate on its own.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation. Read the original article here.