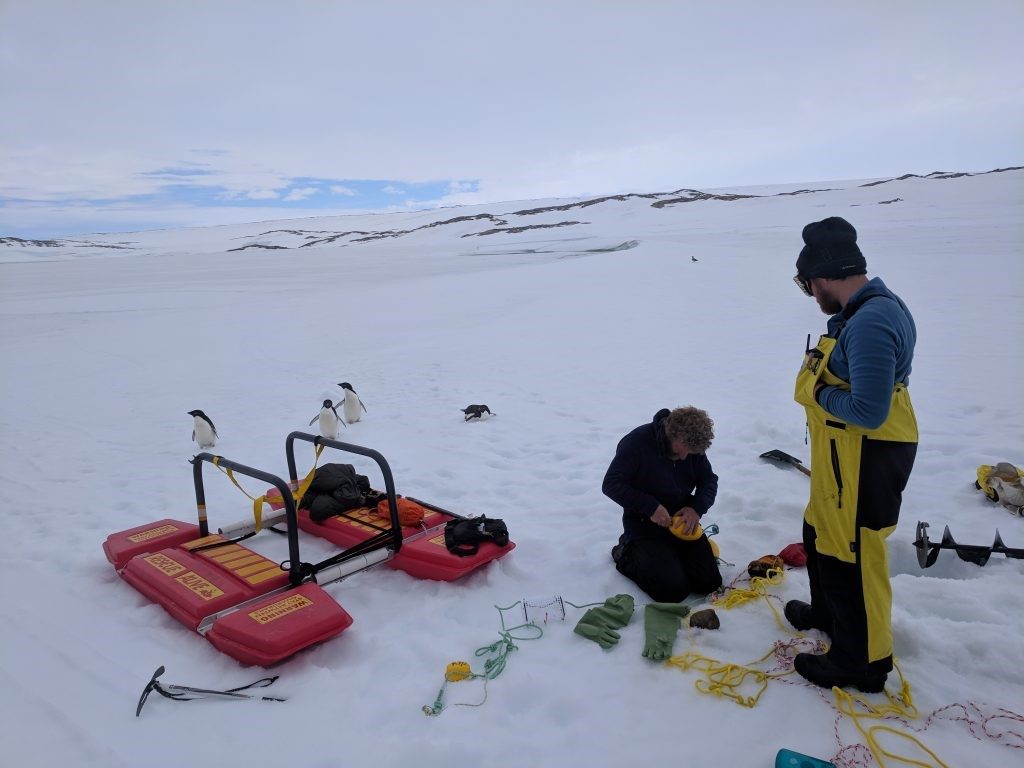

Just came to say hello! Image – Darren Koppel

Humans have taken on many great expeditions. Whether it’s Lewis and Clark exploring the West, Amelia Earheart flying across the Atlantic and Pacific Ocean, or getting yourself to the kitchen for a glass of water after big night.

Expeditions have led the way to many discoveries, challenging and inspiring generations that have followed. But they can be (and have been) extremely problematic. Harsh conditions and infectious disease have caused loss of life for crew, Indigenous peoples’ have had their cultures and populations decimated and local environments have been forever altered. Expeditions can leave a legacy of impacts that continues long after the explorers have gone.

“But what does this have to do with science?!” we hear you scream. If you’ve been following us lately you might have seen an extremely cute video of a penguin jumping on board a little research boat (scroll down for the video if you missed it and start following us on social media pls). Turns out we’re not just in Antarctica to look at cute penguins (who knew?!). Together with the Australian Antarctic Division and University of Wollongong, our scientists are braving the cold to work on some very important environmental management research (don’t worry, we explain what that means below).

Paying the price when you leave it on the ice

There have been a lot of expeditions in the Antarctic (if you don’t believe us just check out the Wikipedia page). They’re an important part of research, allowing scientists to collect data from one of the most pristine environments on the planet. You’d think that when heading out to explore a landscape like this that humans would leave it in the same condition they found it. Historically, that wasn’t always the case.

It was only in 1991 that the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty came into force. The Treaty protects Antarctica as a natural reserve devoted to peace and science, and this includes waste management principals. Prior to this, nearly all waste generated at stations in Antarctica was either burned, buried, or pushed into the sea (and most of it is still there). Cleaning up historical waste in Antarctica is expensive and logistically tricky. Disturbing these areas may also cause more damage than just leaving it untouched.

Most of the pollution in Antarctica has come from historical waste dumps, abandoned stations or fuel spills, and some of it has important historical value. Across the bay from Australia’s Casey research station is Wilkes, which was abandoned in 1969. Here you’ll find machinery, old food, oil drums, gas cylinders and laboratory supplies. This is typical of the historical waste from stations and at the moment we don’t know what kind of damage it could be causing to the environment.

Historical waste dumps could be causing damage to the environment in Antarctica. Image – Darren Koppel

Cleaning our act up

To help solve this rubbish issue, our researchers are developing tools and building the knowledge that will help environmental managers in Antarctica make decisions about whether or not they need to clean up, and how much they need to clean up. This is what the team of researchers were working on when they were visited by the penguin border control officer. The project, which is supported by the Australian Antarctic Program and led by Prof Dianne Jolley, will provide science that better informs environmental management in Antarctica.

The team are trying to establish techniques known as Diffusive Gradients in Thin-films (DGT) that monitor contaminants movement in the Antarctic environment. This lets us measure the pollution that is likely to be a problem to the local environment, rather than what may be locked up (and immobile) in the minerals or ice. DGTs are placed in the waters, sediments and soils and use a filter and sticky gel system to capture contaminants. When the DGTs are collected, the contaminants can be investigated and measured to give us a picture of the pollution in the area.

The DGTs measure the portion of the contaminants that can affect organisms. It doesn’t measure what’s locked up in the soils, ice, or sediments. Together with toxicity data from Antarctic organisms already collected by the team, the DGT measurements will be able to tell us more about the pollution situation in the region.

The project is also looking at the toxicity of individual contaminants to Antarctic organisms. This helps us understand how much contamination needs to be there before Antarctic organisms start to be negatively affected in a way that would lead to population collapse. This data will contribute to the development of environmental quality guidelines for the water and sediments. The team of researchers are specifically looking at metal contaminants (cadmium, copper, nickel, lead, and zinc).

Penguin patrol

And what of the border patrol penguin? While the researchers in Antarctica are often visited by the naturally curious local penguin population, it’s rare for them to actually jump onto a boat.

“There was a group of about five of them checking us out while we were working,” Darren said.

“We could see them playing around us, checking out our mooring. Then all of a sudden – poing!”

After asking around the station, it seems like once a year or so someone will have a penguin jump into their boat.

“We’d been out on about eight boating days and that was the first time they had jumped up. Our unsubstantiated unverified uninformed opinion would be that either it’s now that their chicks have hatched they’re freed up to be more playful or that it’s adolescents playing around,” he said.

The research project is set to conclude this year, so we’ll keep you up to date on their findings (and any more cute penguin patrols of course).

We loved science before it was cool