Gravitational waves have seduced scientists for the past 100 years. But why the big fuss? In the wake of latest rumours that these waves may have been detected, we take a look at five things you need to know about gravitational waves.

Gravitational waves have seduced scientists for the past 100 years- but why the big fuss?

Well-known American astrophysicist Lawrence Krauss caused a bit of a stir last week when he tweeted the supposed confirmation of a rumour that these waves had been discovered by the purpose-built Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) in Louisiana.

The LIGO guys were a bit more circumspect. “The official response is that we’re analysing the data,” according to spokesperson Gabriela Gonzalez.

It’s all a bit mysterious, but in the event that they are discovered, we want you to be prepared for possible high-falutin’ BBQ chat. Here are five things you need to know about gravitational waves.

Gravitational waves are ripples in spacetime

If you run your hand through a still pool of water waves will follow in its path, spreading throughout the pool. Back in 1915 Einstein proposed that spacetime is a four-dimensional fabric that can be pushed or pulled as objects move through it.

Like the waves created by your hand, Einstein’s general theory of relativity proposes that violent events in the cosmos such as stars exploding, black holes merging or even the Big Bang itself send ripples through the fabric of spacetime. These ripples are known as gravitational waves.

What he failed to predict was that 100 years later a rumoured detection of these waves would cause mass hysteria in the scientific community, sending ripples through the very fabric of Twitter.

But why do gravitational waves exert such a powerful appeal for scientists?

“It’s a bit like the Higgs Boson discovery from a few years ago in that the existence of gravitational waves is a fundamental piece of physics that underpins our current understanding of the Universe,” said our head of astrophysics Dr Simon Johnston.

“Detecting them would have implications for the whole of physics, not just astronomy.”

They are exceedingly elusive

Scientists are pretty certain that gravitational waves exist. Aside from the fact that they were indirectly detected in the 1970s (leading to the Nobel Prize in 1993), people don’t generally make a habit of disagreeing with Einstein.

But 100 years on from Einstein’s general theory of relativity, why have we still failed to detect them?

“Gravitational waves are incomprehensibly tiny. CSIRO’s own Parkes Telescope was used as part of an eleven-year high precision search for gravitational waves emanating from the merging of black holes.

“Although black holes merging is an extremely violent event and among the strongest imaginable sources of gravitational waves, it’s happening hundreds of millions of light years away and would still only distort spacetime enough to briefly change the distance between Earth and the sun by the width of a human hair,” Dr Johnston said.

“Like the Higgs Boson, we know the waves are there, but LIGO promises to detect them directly.”

Man with a moustache and zany grey hair wearing a tuxedo

Gravitational waves were first proposed by Einstein 100 years ago.

They could have a practical use

“When radio waves were first discovered nobody thought there’d be a use for them, yet here we are with TV and WiFi. The whole theory of general relativity has applications today- your GPS wouldn’t work unless you took general relativity into account,” Dr Johnston said.

“Gravitational waves are one more piece in the puzzle. By detecting them we can examine them, and who knows where that could lead?”

They would open a new window to our Universe…and possibly others

“At the moment we see the Universe with optical, radio or gamma-ray eyes, but directly detecting gravitational waves would provide us with a new window through which we can look at the world around us,” Dr Johnston said.

The discovery of gravitational waves could also bolster inflation theory and with it, the notion that our Universe is just one of many floating around like bubbles in a glass of lemonade. Inflation theory states that the same force that made space expand super quickly at the moment of the Big Bang also created infinite other universes. Some would be identical to our own, with identical galaxies, exact copies of our planets, countries…and even you.

“Once we’ve caught these waves we can examine them and use them to probe the Universe.”

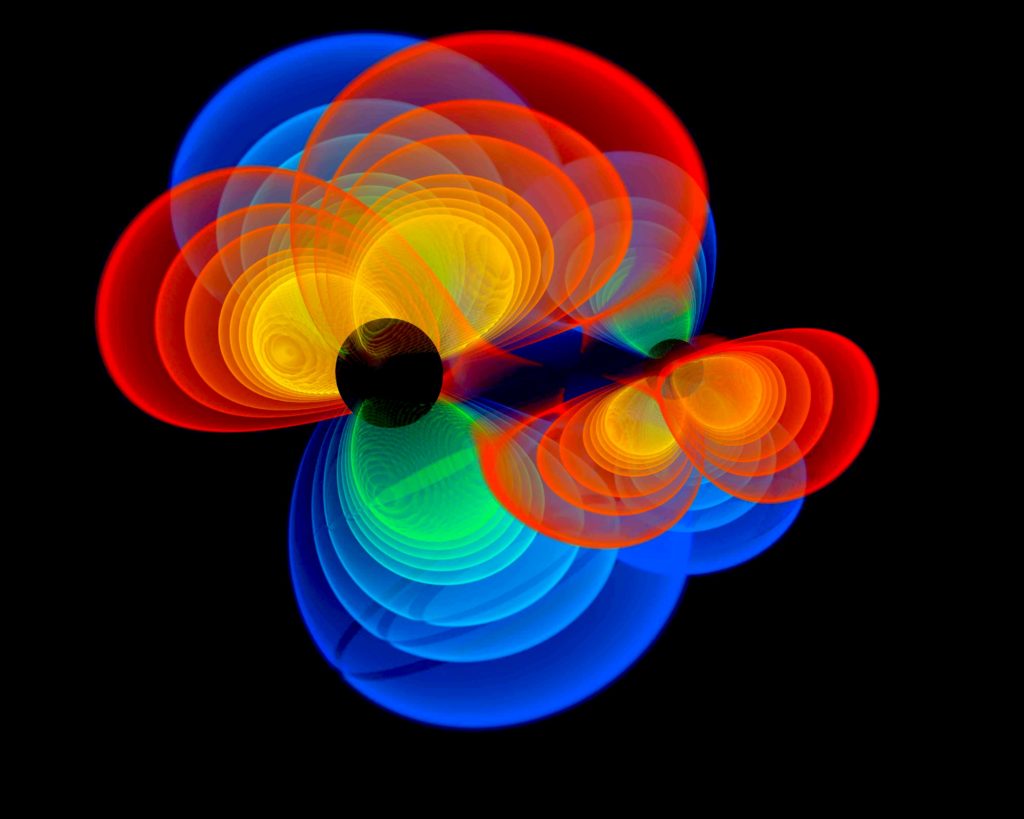

Colourful graphic illustrating two black holes merging.

A simulation of two black holes merging. Scientists believe this violent event would send ripples through spacetime known as gravitational waves. Credit Michael Koppitz/Albert Einstein Institute.

They will let Einstein rest in peace….for now

Although Einstein’s general theory of relativity has withstood every test thrown at it by scientists, directly detecting gravitational waves, still remains the one missing piece of the puzzle. As well as proving Einstein right, discovering gravitational waves would almost certainly lead to a Nobel Prize, so little wonder scientists are tripping over themselves to be the first to do so.

Back in 2014 scientists operating the US-led BICEP (Background Imaging of Cosmic Extragalactic Polarisation) telescope at the South Pole wrongly claimed to have found a pattern in the sky left by primordial gravitational waves produced in the first few moments after the Big Bang. Given the embarrassment, it is little wonder that many in the science community are treating the latest rumours with caution.

But regardless of the seemingly inevitable discovery of gravitational waves and what it does for general relativity, Einstein won’t stay right forever.

“Newton was right for 250 years until Einstein came along. We’ve spent the past 100 years trying to prove Einstein wrong and that time will eventually come as the laws of gravity and general relativity break down in a black hole, so there’s still a problem marrying gravity and quantum mechanics. Discovering gravitational waves is one more step in understanding that problem,” Dr Johnston said.

You can find out more about our astronomy and space science research here.

13th February 2016 at 3:53 pm

The demonstrating scientist does not have to lean over the stretched Lycra frame to retrieve the bits and bobs. A grabber will do the job just fine. The aid that invalids use.

Just a thought.

annorton

13th February 2016 at 3:43 am

A few years ago I was toying with the idea of trying to reduce the number of dimensions we have to “create” in order to be able to try and solve string theory. My idea was that we tend to measure everything two dimensionally, and even in measurement we affect the outcome too, so possibly our way of measuring things in possibly not completely correct. I was thinking that Time and gravity are two extremes on some sort of dimensional scale, one pulling at the other, and in between is energy of all sorts (and space) – so really just four dimensions. Sounds out there I know, but when you start to think that all energies is just one dimension (and gravity isn’t an energy form or maybe it is but its somewhere at the other end of the scale, and time is at the other end. Anyway, time too, is only ever linear, it can be stretched, it can go faster or slower, but generally remains around a constant of say 1 (again, relative to our perception, but important none the less), but it never goes backwards, never gets below the ideal Zero to become negative, but it could actually speed up and go extremely fast, like say when you have a very big explosion. I know this is a non-expert persons idea and I haven’t even come close to the sorts of mathmatics some physicists might have grasped, but then I thought, so if we are able to restate E=mc^2 into a figure for mass (where the speed of light is a factor of time and distance) then you could use the mass of two figures and solve using the gravitational constant theory. So theoretically, how much energy is required to travel between two masses, and what is the gravitational attraction between each. Not sure if it works for positrons or neutrons, or whether it works between planetoid masses too. My calculus is terrible too, and quite rusty.

Anyhow, I think its great to be able to measure waves of gravity, when we’re actually on a mass that creates its own gravity, and not a zero gravity environment (which I guess is kinda impossible. Always found it curious as to all the graphic representations of gravity themselves are two dimensional, but I guess how do you represent a wall or wave expanding like a balloon.

13th February 2016 at 3:47 am

Sorry bout that, just re-reading, maybe not how much energy, but how much gravity?

19th January 2016 at 1:00 pm

Logically, if a gravity wave would be associated with a distortion in time, effectively there would be a form of time dilation. Rather than a gravity wave, it should be possible to instead seek such a time-distortion. Has anyone tried/demonstrated this?

But you cannot do this locally. Because of the time-distortion, your “very accurate stopwatch” will also run slow, so that the distortion will not show directly. See also frankaquin0’s comment of yesterday. Would such a distortion be visible somewhere in space? Perhaps an implied really big interferometer?

(Do I have egg-on-face for this question? Sorry I haven’t read Einstein’s General Theory. But at least I have given thought…)

18th January 2016 at 4:23 pm

Here’s a WAG: Isn’t it possible that a gravity wave passing by could alter space-time locally in such as way as to make detecting it impossible e.g. by stretching space or shortening time so as to cancel out the effect you are looking for?