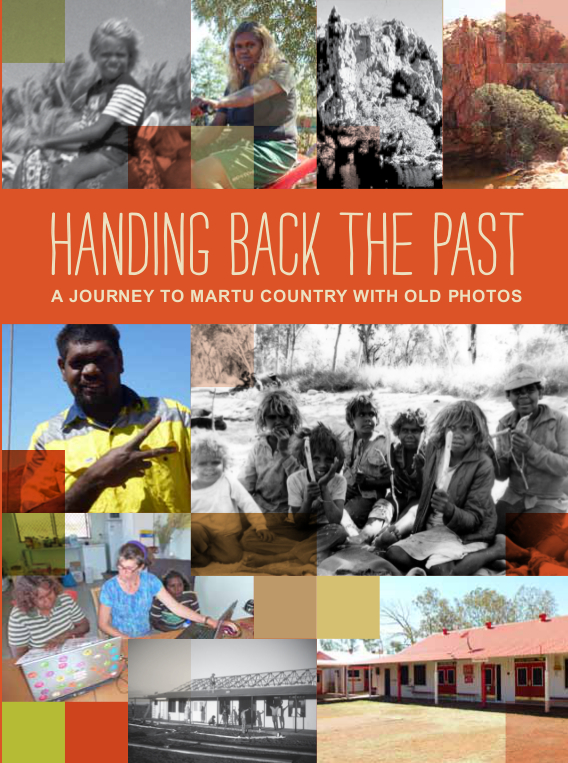

Any film that can make you nostalgic for a time and a place that you’ve never known is doing something right. That is the power of Handing back the past: a journey to Martu country with old photos, a new film by CSIRO ethnoecologist Fiona Walsh. We’re transported to Australia’s Western Desert, home of the Martu people, where Walsh narrates the story of her return in 2011 to a remote Aboriginal community, Parnngurr, with a large collection of photographs she took while working there in the 1980s and 90s. She wrote, directed and produced the documentary, her first, while working on a collaborative biodiversity project between CSIRO, Rangelands NRM and Martu. David Nixon, editor of the popular ‘Bush Mechanics’ series and now an ABC Open Producer, has made a nice contribution with the editing and sound.

Any film that can make you nostalgic for a time and a place that you’ve never known is doing something right. That is the power of Handing back the past: a journey to Martu country with old photos, a new film by CSIRO ethnoecologist Fiona Walsh. We’re transported to Australia’s Western Desert, home of the Martu people, where Walsh narrates the story of her return in 2011 to a remote Aboriginal community, Parnngurr, with a large collection of photographs she took while working there in the 1980s and 90s. She wrote, directed and produced the documentary, her first, while working on a collaborative biodiversity project between CSIRO, Rangelands NRM and Martu. David Nixon, editor of the popular ‘Bush Mechanics’ series and now an ABC Open Producer, has made a nice contribution with the editing and sound.

When we’re introduced to Walsh, she is nervous to see what has become of the community of Parnngurr and the Martu people who call it home in the 20 years she has been away. The stakes are high. The establishment of Parnngurr in the 80s was part of the homelands movement, unique in the world for bucking the emergent global trends in development. The Martu turned their backs on the Western way of life presented to them in the missions and mining towns and returned to live on their country, on their own terms. Walsh arrived soon after, working as a junior biologist, and so the photos she took then capture a truly unique moment in time, a sort of renaissance for Martu culture and custom.

It all sounds very romantic but that was then and this is now. How did things work out? Add to this sense of the unknown, Walsh’s anxiety about how the photos will be received. Will anyone care? Will anyone remember her? And, of course, our own perception about what awaits her in Parnngurr. The narrative about remote Aboriginal communities we are familiar with from the mainstream media all but assures us Walsh is heading straight into a disaster zone. The reality is much more rewarding; Parnngurr is a vibrant and unique place.

As Walsh mentions, her repatriation of these photographs to the Martu is part of a worldwide movement that is seeing past records and artefacts being returned to Indigenous peoples by museums and researchers. It’s an important movement, particularly in Australia where so many Aboriginal people have been displaced and separated from their families and country. Many people are actively researching their own family history and so records like this would be a great boost in piecing that together.

For other researchers working with Indigenous peoples, Walsh was keen for this documentary to highlight two important ethical obligations. The first is to ensure people’s knowledge and practices are recorded accurately and in a way that is true to their local meaning and intent. The other is to ensure records, such as photos and research findings—both old and new—are shared with the people who rightfully own them, in a medium that is useful to them.

Behind the immediate account of repatriation depicted in this film lie some more subtle threads to the story. In practical terms, the plants, animals, medicines and hunting and land management techniques that were fastidiously documented by the young biologist serve as a valuable reference. It is a resource that helped the Martu with their successful Native Title claim over an area of 13 million hectares. Nowadays, this resource is used by the Martu heritage and land management organisation, Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa (KJ), and the more than 100 Martu rangers supported by KJ to work on their country. The records allow them to observe how their country has changed—where weeds have invaded, how animal numbers have dwindled or remained—and they are also a strong reminder of the old ways and laws, which are ever present in the dynamic and adaptive Martu society.

The other great story here is that of Walsh’s relationship with the Martu. The story of cross-cultural relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers in Australia is one that often goes untold. This film gives us a rare insight into what makes them work. Walsh obviously has strong bonds with the community founded on mutual trust and respect. She fitted in comfortably with the Martu women, she says, as they shared similar interests. It’s sad to learn that the women who had adopted her as a sister in the 1980s have now passed on. They had ‘grown her up’ and taught her about that country and a way of life very different from her own.

Walsh draws heavily on the old photographs throughout the film, which is great because they are just so interesting. Her decision to film and document this exercise has turned out to be a stroke of genius. In doing so she has effectively created yet another extremely valuable record of Martu life. Only this time it has the added richness of comparing past with present.

Find out more about Handing back the past or watch it now:

Transcript available here